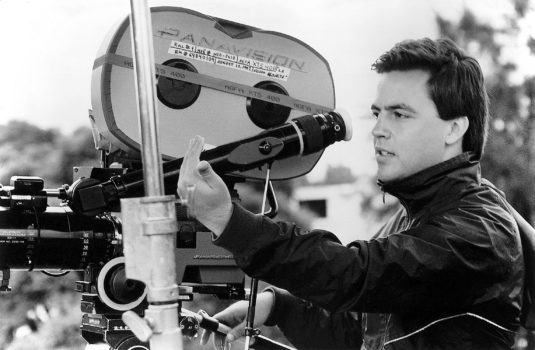

Salvador Carrasco directing “The Other Conquest”

Salvador Carrasco is a film director well-known for his picture “The Other Conquest” (2000), which broke box-office records in Mexico and became an international success. He is also a professor at the Santa Monica College and founder of its film production program. His students have been receiving many awards at international film festivals.

Diana Ringo: Your film The Other Conquest became a big success. However, since then you have not made films, why is that?

Salvador Carrasco

Salvador Carrasco: Partly because I’ve been busy doing other things that are more important in life, such as raising three wonderful human beings. Now that two of them are off to college, I will resuscitate my career. At the risk of sounding a tad defensive, it’s not as if I’ve been wholly inactive in film: I have directed television, written screenplays, and created from scratch a film-production program at Santa Monica College, in which I’ve now executive-produced 20 decent projects. I guess I should also mention that I was attached to direct “The Holy Road,” the sequel of “Dances with Wolves,” which I prepped for 3 years but in the end didn’t happen due to reasons I’m still trying to understand. It would have made a truly wonderful movie.

Diana Ringo: Do you prefer working with professional or non-professional actors?

Salvador Carrasco: I enjoy different aspects of each: generally speaking, the craft and guarded trust of the former and the spontaneity and unconditional trust of the latter.

Diana Ringo: Your film has a lot of mysticism, what role does it play in your life? And what about religion?

The Other Conquest

Salvador Carrasco: None, really. Spirituality maybe… In art, in worthwhile people, in the values we instill in our children. Overall my life is firmly rooted in reality, though one of my greatest pleasures is to wander alone in a historically imposing religious building. Go figure. Last year, for instance, I was in Istanbul and I arrived at Chora Church (a medieval Byzantine Greek Orthodox gem) at closing time. To my surprise they let me in and I spent an hour there by myself… Pure bliss.

I don’t care for institutionalized religion, but I do respect people’s religious beliefs as long as they keep them to themselves. Ideally religious beliefs lead to self-questioning and trying to lead a more spiritual life, which is what I explored in “The Other Conquest.”

Diana Ringo: How did Plácido Domingo become executive producer of your film?

Salvador Carrasco: His son Alvaro is the producer of “The Other Conquest.” Plácido read the screenplay and agreed to be executive producer, which was a risky move on his part since this is a film about the Aztec resistance to the Spanish Conquest of Mexico (Plácido is Spanish), but he believed in what the film had to say.

Diana Ringo: At what age did you want to become a film director?

The Other Conquest

Salvador Carrasco: I became interested in so-called art-house films at around 11, which helped, but the first actual move came after high school. I was interested in too many things and couldn’t make up my mind, so I opted for a profession in which I would be able to purse all the interests I had. Film is ideal for that.

Diana Ringo: Cinema is a synthesis of various arts. Which art is the most important to you?

Salvador Carrasco: I couldn’t really prioritize. As a director, it’s essential to read as much as possible, visit museums, and listen to music —literature, visual arts, and music—, among other things. Doing that not only informs what we want to talk about, but it also helps us express ourselves better.

Diana Ringo: What film are you planning on directing next?

Salvador Carrasco: I am currently developing a TV series for an outlet such as Netflix. If all goes well, I hope to direct the pilot. Aside from that, I’m planning on directing a short film this year. Incidentally, these projects will be produced by Carrie Finklea, who was a featured filmmaker at your festival (PIFF) last year!

Diana Ringo: What is more fulfilling for you, to be a professor or a film director?

Salvador Carrasco: It’s two different professions that appeal to different areas of one’s being, but they complement each other well, at least in my case.

Diana Ringo: How much time do you spend on the shooting of your student’s films?

Salvador Carrasco: A maximum of 8 days of shooting. Post-production is another matter…

Diana Ringo: Do you sometimes have conflicting views with your students? How do you solve these problems?

Salvador Carrasco: The way I understand my role as a teacher is to help my students fulfill what they set out to do, though at times, due to experience, I might have a better idea of what lies at the end of the road. On principle I listen to them, and if I find a conflicting view that they feel passionate about and has merit, I’m glad to pursue it. There is no room for egos in this kind of collaboration.

Diana Ringo: Some films which your students have made have high production values. How are they financed and what is the maximum budget for student films at your college?

Salvador Carrasco: The average range has been between $5,000 and $20,000. The students raise money through a crowd-funding campaign such as Indiegogo, we get some financing from the college itself, and thankfully we were just awarded a grant from the Hollywood Foreign Press Association to further support these films.

Salvador Carrasco supervising the student film “One of These Days”

Diana Ringo: Do you keep contact with students who have graduated, can you tell more about their careers after they finished college?

Salvador Carrasco: Absolutely, and it is incredibly satisfying to start interacting with the more talented ones as real colleagues. Some of them complete their Bachelors studies at a 4-year college or prestigious film school (SMC is a 2-year institution), and others get entry-level jobs in the film industry. Some of the directors and producers of our award-winning films (“Solidarity,” “Cora”) are turning them into features.

Diana Ringo: Is there a film which you have watched many times?

Salvador Carrasco: Several, yes. The first that come to mind in no particular order are “Come and See” (Klimov), “Los olvidados” (Buñuel), “Menilmontant” (Kirsanoff), “Chocolat” (Claire Denis, not the other one by the same title), “Les Misérables” (Lelouch —the great 1995 version with Belmondo), “Open Hearts” (Susanne Bier), “La Bête Humaine” (Renoir), “The Ascent” (Larisa Shepitko), “The Human Condition” (Kobayashi)… and “The Other Conquest,” for obvious reasons (I also edited it, so between that and festivals I’ve seen it many times!). What all these films have in common is that the more I see them the more they speak to me.

Diana Ringo: Are there age limits at your college?

Salvador Carrasco: None whatsoever. We have a policy of universal access. Some of my students are freshly out of high school and some are older than me.

Diana Ringo: Please tell us about the short films you made in university. Who was your supervisor?

Salvador Carrasco: I made several short films that did quite well, fortunately, and allowed me to pursue my first feature. I suppose the standouts were “Marblood,” at Bard College, and “To Fall in Exile,” my senior thesis film at New York University. At NYU my mentor was Chinese director Christine Choy, with whom I remain close friends today.

Diana Ringo: What do you think about the future of independent CINEMA?

Salvador Carrasco: I remain hopeful that cinema will keep evolving, though I also believe we face 3 big challenges today:

• technology makes filmmaking more accessible, which is wonderful, but more questionable movies are being produced than ever before;

• the videogame aesthetic often sacrifices content for flashiness, so it rarely leaves a lasting impression;

• independent movies trying hard to be mainstream or commercial, which defeats the purpose of “independent” cinema.

I strongly believe in making films that one feels passionate about, and if they have something to say and they’re well executed most likely they will connect with audiences. To bring this interview full circle, I was always told that “The Other Conquest” was not commercial, and at the time 20th Century Fox released it, it became the highest grossing film ever in Mexican cinema. You have to follow your own internal compass, and then if things don’t quite work out the way you wanted, at least you keep your artistic integrity alive.