NOCEBO by Faraz Alam

Journalist of the newspaper Prague Telegraph – ptel.cz, Yulia Vovk, took interview with four filmmakers who participated in the short film program of PIFF 2017.

The resulting article “Court métrage — an attempt to stick an elephant in a suitcase” was based on these interviews with the festival participants. Here we publish the original English version of the interviews.

Interview with ONERE director Kevin Pontuti.

Onere Introduction: https://vimeo.com/173978605

Website: http://www.penitentproductions.com/

1) From whose point of view is the story told?

Kevin Pontuti: Most of the film is viewed from a very objective point of view and unfolds in real time. There are no scene changes and only one primary actor. The opening camera angles are from very far away—they are static, long and from eye level, as if the viewer is standing in a Dante-esque canyon. The characters enter the scene, pass by the viewer as the story unfolds, and eventually—leave.

2) What makes this story and characters different or special? How do you find the ways to make the plot and characters unique?

Kevin Pontuti: I typically focus more on mood and poetry than in plot. In ONERE, the plot is very, very simple and resonates because of this simplicity. I often work reductively. The other thing that is somewhat unique with ONERE, and most of my films to date, is the lack of dialogue. The film relies on visuals and sound to tell the story. There is actually very little character development in the traditional sense. The audience connects with the young woman in ONERE because, in the beginning, they empathize with her physical struggle and the god-forsaken cold landscape. As the film progresses, this empathy builds throughout the film and reaches a peak as she exits the frame at the end of the film.

3) Was there a particular event or time that you recognized that filmmaking was not just a hobby, but that it would be your life and your living?

Kevin Pontuti: Although film is now my primary artistic focus, I do create work in other mediums. I come from a studio art background (drawing, painting, sculpture and photography) and later came to film. As I was making, North Passage in 2014, my first film (and a feature) it became evident to me that film was a medium that suited my interests. It took me three years to complete and I did mostly of the storyboarding, editing and visual effects myself, which was a great learning experience, from there I was hooked.

4) Is it harder to get started or to keep going? What was the most difficult challenge in making your film?

Kevin Pontuti: I love the “getting started process” – probably my favorite part. Knowing when to stop can be more difficult. I tend to spend a lot of time in post production, crafting the images so often that it can be difficult.

5) What advice would you give to someone who wanted to dedicate their life to creating films?

Kevin Pontuti: There are so many paths within the film “industry” and I think it’s important to clarify right away, what your goals are and try to imagine where you want to get to. Do you want to tell stories as an independent artist, or do you want to work in a “hollywood-esque” industrialized model? I think there can be value in both of these pursuits and they can often intertwine but I think it’s important to really think about why you’re doing this.

7) What films have been the most inspiring or influential to you and why?

Kevin Pontuti: That’s a very tough question. Where does one start? I think I’m more influenced by directors than specific films. Andrie Tarkovsky has been a big influence creatively and more recently—Roy Andersson. I think his approach to humanism in his films is remarkable and I love the painterly compositions and visual storytelling. I also find his career path to be an inspiration—his resilience and endurance is incredible—such a great comeback story.

I also keep thinking about Myroslav Slaboshpytskyi’s The Tribe (2014) more recently Tim Sutton’s Dark Knight (2017) —two incredible films.

8) As a filmmaker, do you worry about the audience’s reaction to your film?

Kevin Pontuti: Absolutely. I don’t necessarily worry that they’ll “like” the film or make them happy but I’m always thinking about their response and how they may be affected.

For me, the audience is integral to completing the film and I’m always thinking about their reaction. One aesthetic decision that I stand by is I always attempt to leave room for the viewer to help complete the narrative or the meaning of the film (artwork). Some refer to this as “being open ended”. I think it’s more about allowing room for poetic interpretation.

9) What role have film festivals played in your life? Why are they necessary?

Kevin Pontuti: Festivals are incredibly important to developing and nurturing the film community. As a film viewer, festivals are the best way to find interesting films and to experience films in a communal environment. They are still the best venue for finding independent and artistic films. As a filmmaker, festivals are a great way to connect internationally and locally with audiences. The social and education components that happen after hours are just as important as seeing the films.

10) How do you get the most out of film festivals?

Kevin Pontuti: I try to personally go to as many of our festival screenings as possible. One of the best parts of attending a festival is having the opportunity to meet and talk to the filmmakers. I know that as a film viewer. So I try to be well prepared. I think a big part of festival success is doing the research on what different festivals are interested in and focusing our energy to support the festivals that seem complimentary to the sorts of films we’re making. It’s as important to support and grow festivals and independent programs as it is to support filmmakers. So I see this as a two-way street and I think festivals enjoy the energy, efforts and partnership that we bring to the events.

11) Can you describe the responsibilities filmmakers have regarding cultural life?

Kevin Pontuti: I’m sure everyone has a different approach to this. I think artists should have the freedom to decide what sort of work they want to make and to live the life they want to lead. There are so many different paths and I think everyone should be allowed to figure out how they want to use the medium.

12) Do you feel that being a creative person requires that you tell a particular story or touch specific issues? Why or why not?

Kevin Pontuti: No, Not really. I like to give myself the freedom to explore rather than to set specific goals, especially at the beginning of a project. I do most of my brainstorming though a drawing practice that is a mix of storyboarding combined with outlining and mind-mapping. It’s an organic process that I’ve used for a long time that is somewhat intuitive and meditative. As I work, I fill tables up with drawings, note card and reference images as I start to build and refine ideas and structure compositions visually. I often have multiple ideas / sequences developing concurrently and they sometimes cross pollinate. In most cases I’ll write a script too, mainly to help the actors and coordinate the production but usually it happens after the idea has been explored and developed visually. Through this process, certain issues or themes eventually emerge, and then it becomes a reductive process to simplify and amplify the effect, which extends all the way through the assembly, editing and post production.

13) If you could rewrite one part of this short film, what scene would it be? Would the film end the same?

Kevin Pontuti: I don’t think I’d really change anything. We talked about the possibility of adding another shot of the man hanging naked from the tree—a lot of people don’t actually even see him there. It’s very subtle and he blends into background. His presence though is felt and it’s a very important that he’s there.

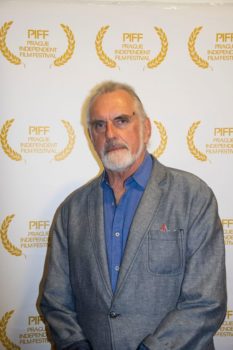

Interview with TIME-RETROGRADE director David Ellis

Exploring a new digital avant-garde.

Over the last 15 years, award winning director David Ellis has emerged notably at the forefront of a new wave of experimental film making. With a fiercely original, distinctive and visionary style of movie making, his works are a personal cinema where traditional storytelling is redefined through the absence of dialogue or defined narrative. In this non-traditional storytelling portrayal, the interplay of image, sound and atmosphere leaves the viewer to create their own narrative in a cinema created as pure visual poetry without the burden of narrative or the limitation of language, intended to be responded to as pure art of moving image and sound. In his exploratory approach to film making, moving pictures no longer need to “make sense” as viewers form their own stories.

Time – Retrograde is a fascinating, almost hypnotic, exploration of sound and moving image, presenting cinema as pure poetic art. Created in the experimental spirit of early 20th c. avant-garde filmmaking, it voyages into a layered surreal abstract digital realm where forward and reverse time motion intersect as sound and moving images slip past and through one another. It was filmed at night on the streets in Lyon, France with ambient field recording audio mix by the director, David Ellis.

1) Please tell about your film and how you worked on it ?

David Ellis: I am very interested in early 20th century avant-garde, experimental films by artists such as Fernand Leger, Man Ray,Viking Eggleling, Hans Richter, Walter Ruttman and others. Many of my works explore influences from cubism, and Russian Constructivist and Suprematist works by such artists as Alexander Rodchenko, Malevich and Lyubov Popova, by employing the design elements as a pure graphic art form. While avant-garde in the same spirit as those early film pioneers, the work is non-narrative in the traditional sense, exploring the moving image, and the inter-dependency of the movement, timing, structure and evolution of the image on the screen with similar qualities in the sound that accompanies it.The work utilizes this relationship of sound and image where sound is not simply a “cue” to “ready” the audience’s responses to the film. The audio is no longer background, nor there simply to fill an otherwise empty space around the visuals, but is on an equal trajectory with the image as an essential component, at times exchanging places with the image, where the image becomes an accompaniment to the sound.

Time – Retrograde was born quite spontaneously, but actually took 3 years to complete.

I was working in Barcelona, during a 3 month film residency, on another challenging experimental film that had become quite an intense project. I needed a break from the project, so very late one night, I grabbed some video clips I had shot recently at night in Lyon, France and began combining them with no attachment to outcome or expectation. I soon realized that a wonderful, magical film was emerging and was instantly excited!! As a filmmaker, I think we recognize it when we have something really good happening before our eyes!! It felt very surrealist and different from other films I was working on. I feel it possesses the same spirit as early 20th c. films, but nearly 100 years later, created with contemporary technology. It was the absence of expectations that allowed for discoveries to be made in layering with glitches and interesting digital reactions between layers. Not wanting to “overpaint” it, I let it sit for a while, and I would watch it many times, always loving it. Over the next 3 years, I worked on editing textures, fades, colors, tempo and created the audio track with my own ambient recordings.

Finally, feeling it was complete and curious to see the public response, I released it in 2017.

2) What makes this film different or special? How do you find the ways to make the film unique?

David Ellis: What makes it different is that it is a rather on-the-edge exploration of non-traditional storytelling in film.The absence of dialogue leaves the viewer to create their own narrative through personal associations. This absence makes the film accessible to audiences of any culture or language.

It is also special, as it is an experiment in the relationship between moving image and sound, and the interdependency of movement, timing and structure with the sound that accompanies it. The audio is another horizontal layer in the film, and not there just as a cue to audience response. And, as are most of my films, it is a visible segment of life that appears and then disappears, as do the ongoing events around us as we live them.

The layering of multiple video images images, the computer generated creation of the spinning clock and digital-deconstruction glitch textures combined with interacting audio layers, all make this film quite unique.

3) Was there a particular event or time that you recognized that filmmaking was not just a hobby, but that it would be your life and your living?

David Ellis: I made my first films as a teenager with an old Revere 8mm camera. Only one reel survives today, but I knew then that I loved it and was fascinated by capturing moving images. It seemed like the expense kept it out of reach for me until I rediscovered it in the 1970’s, and started shooting 8mm,ordinary quotidian subjects and made my first stop-motion short clips. In the 1980’s, I started experimenting with early VHS videos and again, experimented withVHS single frame stop-motion work. I began to seriously pursue photography in the 1980’s and gradually I realized that being a photographer was my passion and became my public persona. I experimented with pinhole photography, Polaroid, vintage box cameras and built my own cameras or combined old box cameras with cut down 60’s Polaroid cameras. Around 2000, it occurred to me to convert some cheap one-time-use low-res video cameras to pinhole, and I began creating pinhole videos. A cheap $18 dollar kids’ webcam was converted to pinhole and I began recording directly to the computer. The rest is history! I knew that from then on, film and experimental film exploration was my passion. Soon, I rediscovered Super-8 and began buying cameras and shooting on film as well as video. I continue to create still images that are extracted from super 8 film and video but filmmaking is my passion and life. I seem to ALWAYS be shooting clips and working!! Making a living??? Well….that’s another story!!

4) Is it harder to get started or to keep going? What was the most difficult challenge in making your film?

David Ellis: For me, it is harder getting started. Like the novelist finding the first word or sentence. I usually have at least several projects going so that when one is finished (“wrapped“), there is another that I continue with. Having an ongoing creative flow makes starting works easier. I sometimes tend to “dance around” an idea for a long time and then ultimately just have to choose a clip and start editing. After that, it takes on a life of its own and discoveries are made.

The most difficult challenge in making Time – Retrograde; Actually, creating the film happened quite spontaneously. I like shooting video in late night streets, as I did in Lyon,France for Time – Retrograde. I had been working on another quite challenging film in Barcelona and late one night, I felt I needed a break from the other film so I just grabbed some of the Lyon clips and started montaging them but WITHOUT any expectations or connection to outcome. Very freely, like sketching! The film just magically started coming together and I loved what was happening as the layers began interacting with each other. I felt free from outcome which I think allowed me to just combine moving images just to see what would happen. The most difficult challenge was perhaps building/creating the computer generated spinning clock and then deciding how to add it to the film. The real challenges came, as I discovered that it really was quite a fascinating and powerful short film, with the adding of fades, color additions and corrections and then to create my own soundtrack with my own layered ambient recordings and mini-audio segments, matching the tempo of the film.

5) What advice would you give to someone who wants to dedicate their life to creating films?

David Ellis: I guess that would be, first of all, to love what you are doing, and believe in yourself and your vision. You have to “show up”!! That is, just keep working at it in some form every day…keep learning and not to be discouraged by rejections…as there are always plenty of those to go around in the art world. Some will like what you do…some will not. Love being astonished!

6) What was the most important lesson you had to learn that has had an impact on your short film?

David Ellis: There are several lessons that I feel are most important. The first and main lesson is, to create and experiment freely and do what I love. To believe in myself and my vision and to just go ahead and follow my heart and curiosity, and not allow that internal “editor”(that is inside most of us) to talk me out of what I am doing. Not to listen to that internal editor saying – “ people will never get this”, or “this is too different and strange” or “maybe non-one will like it but me”. To me, filmmaking is poetry and I am interested in the “essence” and mystery, and not necessarily providing the tidy solutions for the viewers as most main stream cinema does. The second lesson that I feel is very important to me is to find the correct length for the work. A length that says what I have to say, but doesn’t start to lose the viewers’ attention. I don’t want “filler” imagery or as in painting, to “overpaint” the work. You have to know when it’s time to leave the party!!

7) What films have been the most inspiring or influential to you and why?

David Ellis: I really love Jim Jarmusch’s early films. especially an all time favorite, Stranger Than Paradise and Permanent Vacation. His long takes and character studies fascinate me. Of course, early 20th century avant-garde films by Fernand Leger, Man Ray, Hans Richter, Walter Ruttman and Viking Eggeling among others. Film noir is a love of mine too, Especially the Third Man, with Orson Welles. I love Paris Texas by Wim Wenders with Harry Dean Stanton. I also like David Lynch and Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow Up and Red Desert.

8) As a filmmaker, do you worry about the audience’s reaction to your film?

David Ellis: I wouldn’t say that I “worry” about the audience’s reaction, but, as I imagine most film makers feel, I want the audience to be engaged with the work and either enjoy it or have a thought provoking response to it. My work is very experimental, and doesn’t follow the rules of traditional “storytelling”. I guess I could say that I DO wonder if the audience will “get it”, will they have patience for it, or will they be able to settle into a more contemplative space with the long takes and poetic nature of the work when the film is projected onto the screen.

9) What role have film festivals played in your life? Why are they necessary?

David Ellis: They are great for networking globally with other filmmakers. Like it or not, the art/film world likes credentials and validation. It is a fact of life for creative people pursuing creative careers.

Having work selected for screening and the good fortune of winning awards is a very valuable

credential that is looked at by other festivals and by distributors. Festivals provide a venue for filmmakers to share their work with a global audience and an important venue for exposing new ideas and exchanging evaluations that are often insightful and can help us to continue the learning process as directors, producers and camerographers.

10) How do you get the most out of film festivals?

David Ellis: Screening my films and seeing viewers’ responses is very rewarding. Sometimes, the work really moves people and they will come up afterwards and share their feelings. I LOVE seeing so many other filmmakers’ works and enjoy meeting directors and crews and cast, exchanging ideas and networking. I have made so many new and wonderful friends around the world through film festivals.

11) Can you describe the responsibilities filmmakers have regarding cultural life?

David Ellis: I can only speak for myself as a filmmaker. Now there is a huge question! One that would first require a definition of what “cultural life” really is. Is it social, political, anthropological, artistic, spiritual, historic, regional or global?? My responsibility to cultural life is to honor the creative gift I have and make my art, my films, share ideas and beauty and, perhaps to inspire others. Through imagery, I can show the human experience as I view and live it, and perhaps present visual questions for viewers to consider. I am very influenced by Zen Buddhism and the Japanese concept of mono-no aware, or the “pathos in things”. Perhaps my responsibility to cultural life is to create art that invites viewers into a place of contemplation and introspection. A refuge where there is beauty.

12) Do you feel that being a creative person requires that you tell a particular story or touch specific issues? Why or why not?

David Ellis: For me, being a creative person is who I am…how I see and live life. I am not a “specific issue” oriented person, that is , as subjects for my creativity. If I see and experience something that I find moving, empathetic or curious, it will find its way into the work. As a non-narrative filmmaker, the narratives are my experiencing the moment and the creation of the film, and the viewer’s experience viewing it. There is no agenda.The particular story I tell is the story of my experiencing life…the events, places, people and subjects that are part of my journey through this magical and miraculous journey.

13) If you could change one part of this short film, what scene would it be? Would the film end the same?

David Ellis: At this moment, I like the film as it is. I could go in and tweak the graphics a little, but I like its spontaneity and don’t want to “overpaint” it!! The ending would remain the same. I love the spinning clock fade out.

Interview with Varying Chains director Emir Ziyalar

1) From whose point of view is the story told?

Emir Ziyalar: The story is told from his point of view. He is someone who is revealing himself both to himself, to her and finally to the audience. We are witnesses of removal of his shell.

2) What makes this story and characters different or special? How do you find the ways to make the plot and characters unique?

Emir Ziyalar: During the process of writing the script, I don’t think how to make the characters or the plot unique. I just channel my emotions and thoughts directly and I try to stay true to that result.

3) Was there a particular event or time that you recognized that filmmaking was not just a hobby, but that it would be your life and your living?

Emir Ziyalar: I felt that when I shot my first short film. After finishing the shooting through many difficulties, I realized nothing else can challenge me that much and give me that sense of pleasure.

4) Is it harder to get started or to keep going? What was the most difficult challenge in making your film?

Emir Ziyalar: Keep going is a lot harder than starting for me. I find it difficult to stay true to the original ideas and establish a working bridge between the filmmaker and the audience. One has to sacrifice from one of it most of the time and those sacrifices sometimes demotivate the filmmaker to continue. In this film the most difficult challenge was my own psychology, because I was immersing into it very much and the film was quite dark, so I had a dark time together with the film until I finish.

5) What advice would you give to someone who wanted to dedicate their life to creating films?

Emir Ziyalar: In filmmaking there are so many things that go wrong. It is almost all about how to manage those problems and my biggest advice is to embrace that fact and try to react to them in the most efficient and productive manner.

6) What was the most important lesson you had to learn that has had an impact on your short film?

Emir Ziyalar: In the shooting of one of my earlier films, we lost a whole days footage because of a technical error while dealing with the data. So this time we were extremely careful and had a good DIT on set. During the rush of the set some simple errors like this can occur which can result in a terrible situation.

7) What films have been the most inspiring or influential to you and why?

Emir Ziyalar: Any film of Stanley Kubrick is a big inspiration for me. His mastery of the craft always impressed me. Especially the cinematography of his films and the way they are built regarding the narrative. Also some surrealist films have a big influence on me such as Eraserhead or The Holy Mountain. Another director who created some of my favorite films is David Cronenberg and I would say Videodrome, Dead Ringers and The Fly are influences to me. Regarding the classics, I really enjoy the films of Ingmar Bergman, especially The Seventh Seal and Persona.

8) As a filmmaker, do you worry about the audience’s reaction to your film?

Emir Ziyalar: When I create the film I don’t usually think much about what the audience’s reaction is going to be but when I present the film I am very interested what do they think and how do they interpret it their own way.

9) What role have film festivals played in your life? Why are they necessary?

Emir Ziyalar: I did not participate to many films festivals yet but as far as I can tell, they are a great opportunity to share your film with others and get to know like-minded people.

10) How do you get the most out of film festivals?

Emir Ziyalar: I think the most important thing is to attend every film on the program as well as to attend any other event of the festival. This way one can watch many different things and talk about them with others. Networking is also very important to filmmakers in order to share your work and look for opportunities.

11) Can you describe the responsibilities filmmakers have regarding cultural life?

Emir Ziyalar: Film is a great medium to share emotions, ideas or thoughts. There are many different filmmakers some focusing on social aspects of life, some focusing on psychology of human behavior or some focusing on pure entertainment. No matter which direction one chooses, a filmmaker should contribute to the society by creating films and sharing their unique voice. This way the society can have a pool of different colors which they can explore to find what they look for.

12) Do you feel that being a creative person requires that you tell a particular story or touch specific issues? Why or why not?

Emir Ziyalar: I would not say being a creative person requires you to touch a specific issue. We all have something we would like to express. This could be anything. I think one should express what one feels and should stay true to his ideas, opinions or emotions.

13) If you could rewrite one part of this short film, what scene would it be? Would the film end the same?

I would not rewrite a part of my film because what matters is what we create in that very moment of writing or shooting. We can turn back and always think of different ways to do it but I think that would not be staying true to it. For me a film ends in every creative aspect when we complete it.

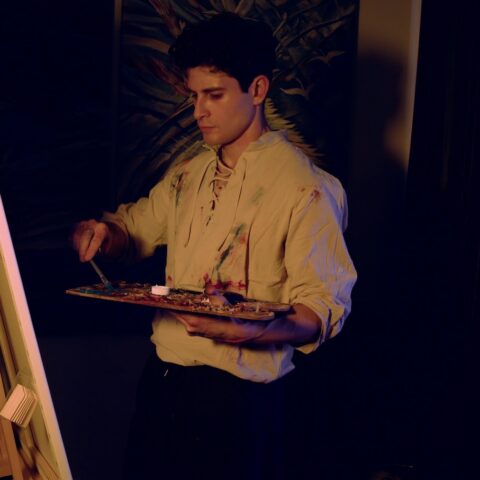

Interview with NOCEBO director Faraz Alam

1) From whose point of view is the story told?

Faraz Alam: The story is told by the soldier who is both the ex-lover and the victim of the nurse (one of the many). Besides being ill and mentally handicapped for having being infected with syphilis, he carries the pain of a heartbreak, which devastates him the moment he realizes he is just one among many so-called lovers of the woman: she took her revenge against every single one of them, after having been sexually violated while working in the hospital.

2) What makes this story and characters different or special? How do you find the ways to make the plot and characters unique?

Faraz Alam: I think this is a story that triggers the need to define the good and the bad (the politics of revenge), but at the end leaves the viewer without a proper answer. The story is controversial and I tried to tell it in the most unbiased way possible. When I was researching about this historical event, I was introduced to contradictory opinions about the nurse. I didn’t mean to take a stand and I wanted people to approach it individualistically. Therefore I chose to narrate the story through a brain wrecked, heartbroken ex nazi soldier. Whereas the unnamed nurse, being the character around which the story was created, is someone that does make you empathize with her for the violence she has been victim of and, at the same time, doesn’t appear as a heroine who fought back against the evil. Her character leaves reflections open, and so does the whole story. I guess this is what I find special about it.

3) Was there a particular event or time that you recognized that filmmaking was not just a hobby, but that it would be your life and your living?

Faraz Alam: Actually, it was not a single event or moment that made it happen: it’s been a perpetual series of interactive experiences that provoked my curiosity and my interest. I have always been fascinated by different means of communication and art forms: I started exploring visual arts through photography amidst my bachelors in computer science until I finally took the leap to filmmaking. Besides my passion for the visual language of the film, I have to say that having my family living in a war torn country, with limited access to information and a restricted ability to communicate especially outside, definitely triggered my need and will to speak, communicate, make myself and others heard.

4) Is it harder to get started or to keep going? What was the most difficult challenge in making your film?

Faraz Alam: According to my limited film experiences, the tougher bet would be to keep going. One of my recent experiences is an allegory for the same: a film production which did not work as planned. Probably your expectations become higher both on yourself and generally on the people you work with, and the moment you think you have everything under control, you have to adjust to the truth that it may not be enough. But I guess acknowledging vulnerability makes us stronger and inspires innovation and improvement. Sometimes There’s something about letting a moment happen. Your best-laid plans cannot exceed spontaneity.

Honestly, Nocebo was more by the book than I imagined. We were shooting in the FAMU studio in Barrandov with limited availability of film stock, made everything more “controllable” hence smooth. Besides having an incredibly passionate creative and technical crew, I was also lucky in having two very good actors Eva Larvoire and David Diaz, both Prague based artists, who further paced the production from day one.

If you recruit people just because they can do a job, they tend to work for your money. But if you hire people who believe what you believe, they’ll work for you with sweat and blood and tears.- Simon Sinek

5) What advice would you give to someone who wanted to dedicate their life to creating films?

Faraz Alam: Do it because you cannot do anything better! But be prepared because it is a highly demanding kind of job and the odds are sometimes huge – but they may as well be overcome more frequently that you can imagine the moment you feel stuck. Vivid skepticism is optimism’s best friend.

6) What was the most important lesson you had to learn that has had an impact on your short film?

Faraz Alam: Filmmaking is a holistic art both in the process and in the execution, but it doesn’t fail in reminding that, at times, you have to pull yourself together on your own.

9) What role have film festivals played in your life? Why are they necessary?

Faraz Alam: Filmmaking like many other art-forms thrives on distribution. Some film festivals offer a critical platform to help take the communication forward. It not just provides a platform to seek critique or acknowledgement from but it also nurtures relationships which might benefit your future ventures and I believe it has a huge value for not just an aspiring filmmaker. Also, when it comes to short films, the film festivals are among the few if not the only platforms of distribution and they help you get our work screened while introducing you to other people’s work.

11) Can you describe the responsibilities filmmakers have regarding cultural life?

Faraz Alam: First of all we must listen to stories and then we have to tell them. No story can be told if there is no proper deep listening to what needs to be told. I think the is something important and priceless, in a society which connects us 24/7 to everyone without letting us listen to understand properly. You are on your phone and you get a whatsapp message, then you are on whatsapp and messenger comes, the newsfeeds are almost incoherently aggressive…but how many times to we actually listen to understand? In a word, I think we create culture when we create transmission of stories, memories, emotions and understanding and this is what filmmakers should do.

12) Do you feel that being a creative person requires that you tell a particular story or touch specific issues? Why or why not?

Faraz Alam: In my opinion, being creative does not require for the artist to meet any specific standard, both in terms of content and in form. Creativity is more a personal attitude than a skill. It is the way you see things and you are able to make your ideas and perspectives come to life. Creativity and arts are not limited to certain languages. One may be creative in conducting a corporate job or language classes in a unique way. It is about sharing your inner self somehow. Creativity is selfish and selfless at the same time; you are ready to do anything to make your expression happen and you let it go the moment you do.

Having said that, when your creativity allows you to give a new perspective and evoke a sense of change in people’s lives and in society, that is really worth the struggle.