Alex Proyas

Legendary film director Alex Proyas famous for his iconoclastic films “The Crow”, “Dark City” and “I Robot”, discusses his work during the lockdowns, murder of culture and xenophobia in Australia, plagiarism of his films by mainstream Hollywood and censorship. Alex also shares with Indie Cinema his plans for the future – new films, TV series and VIDIVERSE – a new online film platform for independent filmmakers.

Alex, is it difficult to retain an independent point of view in these difficult times today?

Yeah, I think it’s difficult to retain your independent point of view as a person in this world really, isn’t it? I mean it’s getting harder and harder to remain an individual. My whole philosophy of life is being built on the strength of the individual voice. And unfortunately, the whole world is moving into a more kind of stricter, less free, mindset. I guess the more human beings inhabit this planet, the less individual freedom each person can have. But, yeah, so it is a challenge, as an artist and as a human being inhabiting the planet Earth in 2021 to retain any level of individual authority, autonomy. It’s really hard, and you think about our children and that’s even more of a concern, I’d say. As a filmmaker, I’ve been through the whole gamut of working with the big studios in Hollywood which are traditionally not a place to speak with an individual voice. And I’ve done my best to maintain that individual voice. And I’ve usually failed dismally working with them. Of course, the more, the bigger the budget, the more people working on the production, who are scared of losing their job. And the more fear surrounds you as a filmmaker, the less freedom you have, just like in the real world. So, I’ve chosen to try and move away from that world back into a more independent model of filmmaking, because for the very reason that I want to retain my own freedom, be able to speak with my own unique voice and display my own unique vision. I fell in love with filmmaking as a kid who had an original voice, that’s what I gravitated towards as a filmmaker. And at my age I want to be able to get right back to that unique vision that I feel I have and I want to be able to work within my films.

And you organized your new production studio (Heretic Foundation) last year, yes?

It’s been almost two years. I started building it in 2019. And it’s taken us this long, we’re now fully engaged with making productions, and facilitating productions for other filmmakers, and we’re very busy. But it’s taken this long to get the technology worked out and the crew, the people that I work with organized and we’re building a business from scratch. So, it’s taken a while and we’ve done it through COVID and all the lockdowns that have happened and we haven’t been able to get our equipment, our computer gear when we wanted it because being in Australia we’re far from the rest of the world and things were delayed and so it’s taken probably double the time that it would have taken if we weren’t all living through the same nightmare that we continue to live through right now.

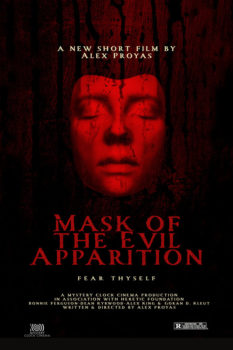

Film still from “Mask of the Evil Apparition” (2021)

And how do you manage to cope with working during a lockdown?

It’s difficult, it’s very difficult. My country here, it’s a disaster in terms of the government managing the problem. We accept that there is a problem but the government chose to turn it into this panic, they thrive on fear and they bungled the deployment of the vaccine. They took way too long to deploy the vaccine. And people who wanted the vaccine couldn’t get it. And now, months too late, they’re adopting really totalitarian draconian measures to force people to get the vaccine, but there is no vaccine available, it’s still really slow to come in. So, they’re doing it to present this illusion that they didn’t make a mess of it in the first place, you know? It’s a mess. It really is a mess. As I speak to you right now, Sydney has been in lockdown now for over eight weeks. I think this is a ninth week. Melbourne, who’s our southerly city, they’ve been in lockdown for 200 days of the last year. 200 days they’ve been in lockdown. I don’t know how those they’re coping with it. Here we’ve done much better, but our lockdown is continuing, we think till Christmas, we’re not sure, we don’t know, they won’t tell us. They keep changing the rules of when they’re going to release us from this crazy situation. And yet, they keep making the rules harder to maintain. Now we have curfews in parts of Sydney, which means you can’t leave your house between nine o’clock at night, and five o’clock in the morning, you’re stuck in your house. And this is all with Delta, which is proven to be not as deadly as the original COVID.

There was also news yesterday that vaccines don’t work against Delta.

That we don’t know, but it doesn’t matter. Because our problem in Australia is they’re not giving the vaccines in any quick measure to people who want the vaccine. So it’s actually a whole other issue that in other parts of the world some people don’t want to take the vaccine, and we have people here like that as well. But that’s actually a moot point here, because the reality here is, even if you want the vaccine, you can’t get it. You can get AstraZeneca, which people have problems with, you can’t get the Pfizer and all the other ones that that seem to be okay. But then anyway, this is a rambling way to answer your question. The answer is it’s very hard, and it continues to be hard.

We just made a film. We just shot a feature film in the last few weeks. With a very small crew. The advantage that I have is that my method of production, which is LED screens and virtual production, means that the crew are in one focused, isolated studio. They get tested in the morning – everyone gets tested. With these quick tests that tell them straight off, I think within a few hours, whether they’re positive or negative, and they can all work and they’re effectively in a bubble. They’re in the city. And they have to be from certain areas of the city because we can’t travel from out of a 10-kilometer area. But once we get them into that situation, they can work, they all mask up during the production, etc. but they manage, they got through the production, but it’s really, really difficult. And my problem right now is everyone in the film industry has been through these measures but we were doing just fine until this incredible mess that was created by the government. And now we’re being punished for that way after everyone. We hear about people in other countries who are coming out of their lockdowns and Delta statistics are plummeting. So, here up until like two days ago, the government was talking about zero transmission. They’re trying to get it to zero and that’s like, that’s impossible. That’s absolutely impossible. In other countries they have proven that it’s impossible, they can’t hope to get it back to zero. It’s just not going to happen. They have to accept that it’s going to keep spiking. The infections keep going up and we have to manage that, and the only way to manage that, is through vaccination and not locking down the commerce. I mean businesses are going out of business. I’m one of the lucky ones. We’re managing to keep working so far. Touch wood, but I know so many people, their businesses, their family businesses are falling over. It’s a complete disaster. And the government just won’t accept the problems. They just keep blindly going forward, you know?

Film still from “Mask of the Evil Apparition” (2021)

Film poster of “Mask of the Evil Apparition” (2021)

Your new short film, “Mask of the Evil Apparition”, how it is tied in with the Dark City universe?

I wrote the script around the time that I made “Dark City” and there are some common threads in it. And I’ve sort of said to people, it’s kind of in the Dark City universe, which it kind of is, it’s got very similar thematic ideas, and it’s come from the same era of my life where I created “Dark City”. So it’s very much a cousin of Dark City in many ways.

And you’re also planning a “Dark City” TV series?

Yeah, I mentioned this to someone, it’s very early, we still write scripts, we’re still a long way away from getting it made. But I hope next year we’ll be we’ll be making it.

How did you first decide that you wanted to become a filmmaker?

It’s so long ago now I almost don’t remember. I saw many movies. My father in particular used to love going to the movies, my mother did as well. And my father was really a huge movie fan. And he would take me to all the movies when I was a kid. And, I remember how he took me to see “2001: A Space Odyssey”, which he knew nothing about. I certainly didn’t know, was probably six years old when he took me to see it. But I remember the experience to this day of seeing that particular movie. And it still remains one of my favorite movies. At the time I didn’t understand it, of course, when I was six years old. But it had a huge impact on me, just the size of the screen, the sound, the imagery that was taking place. It was such an all-consuming, immersive experience for someone of my age, or for anyone really, that it created this deep impression. And so I wanted to become a filmmaker from a very early age. I started making films when I was 10 years old, and I’ve been making films ever since. So it’s been with me all this time, you know?

How did you first start making music videos?

I haven’t made a music video now for probably 25 years. But when, as a young man, when I came out of film school in Australia, we didn’t have a very big enough film industry here. And we still don’t really, but it’s a little bit better now. But there were only so many places you could go to make film, to be a filmmaker. I came out of when I went through film school, very young, I think I was still 20 years old when I graduated film school. After three years, I got in, I lied about my age, and they let me in when I was 17, I was actually too young to be allowed in, but somehow, I got in.

And I came out of film school and I didn’t know what to do. How do I make a movie now? There’s no Hollywood industry infrastructure where I could go and work for other filmmakers and learn on the job or whatever. So, my only choice was to start writing scripts and to find any other form of filmmaking I could do, and I happened to have a lot of friends in bands at the time.

It was the 80s and it was very popular to being in a rock band in Australia. It was a well-supported industry at that time. So, a lot of friends who were in bands and I went to them saying, do you need a music video? This is in the early days of MTV and some of them said, yes, we have no money, or some of them said, yes, we’ve got $50, here you go. And we managed to put music videos together just because we liked that marriage of music and image. And, yeah, I’ve had a few successes that way. I very much like the marriage of music and imagery, and again that’s something I picked up probably from Stanley Kubrick, as he’s affected me in many ways. And strangely that fit into my music videos days, because I love marrying music and image together. I think it’s a very powerful combination.

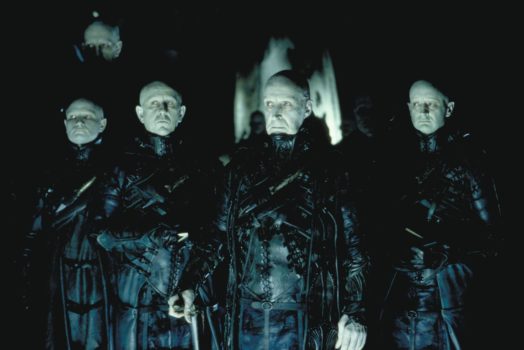

Film still from “Dark City” (1998)

And was it difficult to transition to making films from music videos?

Not really, because it was what I always wanted to do. We were doing music videos, because that was the only form of filmmaking anyone would pay me to survive and do. And my first feature came about through various channels with the music video world. For me movies came first and music videos were a stepping stone towards making movies. I still enjoy making short films, I think the short film medium, for me, is great fun. It’s a little bit like, I quoted as a writer who writes novels, which is a feature film, but I like to go back and write a short story occasionally. It’s just, it’s just good. It’s like a short thing you get in, you do it quickly, usually finish it fairly quickly. And it can be a very powerful genre.

Your films “The Crow” and “Dark City” were very original and influential. How do you feel personally when you see movies which are clearly influenced by you?

Yeah, I feel like calling my lawyers most of the time. (laughs) But I can’t afford the expensive lawyers, you know? Yeah, there is a difference between being influenced and being an effing plagiarist. And being influenced, I see nothing wrong with that, I get it, I’m influenced too, by many things. We are all influenced. But as I say, there is a fine line between influence and plagiarism, and plagiarism, I have no time for, and that’s happened to me, I believe, on several occasions. But you can’t win that battle, because someone says it just sour grapes, the movie that ripped off your ideas made more money than your films, or you’re just bitter about it. So, you just can’t win. And as I say, getting into legal battles over such things, to me it’s a pain that I have no time in my life for. I’d rather spend my life being hopeful and positive than being engaged in legal action against people that I really don’t want to be in the same room with.

Film still from “The Crow” (1994)

Your movies were kind of ahead of their time. And for example, “The Matrix” was very much influenced by “Dark City”.

Yeah, thank you. I mean, it’s very clear to me, where the ideas have come from. Like the Brandon Lee’s long trench coat in “The Crow”, which was then used in almost every other movie, including “The Matrix”, “Blade” and many other movies. You know, this became the preeminent early 2000s sort of cyberpunk Gothic superhero guy and girl. There was also those “Underworld” films, that was the other one that basically ripped off that whole that whole look.

I mean, to me, it’s just kind of pathetic in many ways, because Brandon and I invented that iconic style. And I know exactly where that’s come from. I went to Brandon Lee and said, I want this character to have like some sort of a cape you know, like Batman, I want him to have a cape, because I love that silhouette of this guy in black, with this long thing that goes down to the ground, it’s a very powerful image, from “Nosferatu”, and “Batman” and all that sort of stuff. But I said it would be stupid if you had a cape, it’s got to be something that is like a modern, contemporary urban version of a superhero’s cape. And we came up with the long leather coat for this very reason. We came out of a stylistic necessity, it came out of story and narrative, and character.

And that’s why I’ve come up with the imagery, whereas the other films that have borrowed, if to be polite, or ripped off this idea, they’ve just gone “hey, it looked good in “The Crow”, let’s do the same thing”. So, to me it’s kind of a pathetic way to kind of create visuals, and there’s a lot more in my films that I feel that way about. I’m not to say that I’m completely innocent. I mean I’m sure I’ve stolen things from other people without realizing it. Because my blood runs cold if I see something in another film that I’ve seen, and I’ve gone, oh, my God, that’s where I got that idea. I feel really guilty and really hopeless about that, whereas I’m sure that the filmmakers who’ve ripped off my imagery, don’t feel that way. And that’s my basic annoyance at it. It’s okay to do it, but don’t do it intentionally, cynically, just to profit from it. Do it, because you really do love that thing that someone’s done it. And then be honest about it, say that’s where you got the idea, at the very least, rather than pretending that you just kind of came up with the same idea at the same time?

Do you have any close friends who are also filmmakers, film directors, film producers?

Yes, of course. Yeah. I have many friends and many very prominent friends who are filmmakers and prominent filmmakers rather than prominent friends. I like to think my friends are all on the same level, but there are prominent filmmaker friends. That, yeah, of course, I mean I’ve made many friends, I used to live in Los Angeles, I no longer do, but I lived in LA for many years. And you know, everyone’s a filmmaker in LA. So, I made a lot of friends at the time, who are filmmakers and continue to be very successful filmmakers. And, look, the thing about us here in Australia is that basically all Australians are a little bit xenophobic. They’re a bit fearful of the outside world, which goes back to what we were saying about COVID, and the response to COVID right now, in response to immigration, and all sorts of really bad things about the Australian psyche.

And one of the other bad things about the Australian psyche is that everyone feels very threatened. It’s a very small film industry, everyone feels very threatened by everyone else. Whereas in Hollywood, what I was really encouraged by when I first went there, is everyone is embracing of you, and everyone wants to help, because at the end of the day, they want to make money out of you. But that’s fine. Doesn’t matter what the reason is, everyone is very generous and very helpful. And no one feels threatened. If anything, people want to, like, grab hold of you to make money out of you and make a success out of you, if they can see you’ve got a talent of some sort. So, I found that really refreshing that everyone’s sort of jumping in, helping people out.

So, like, if I made a movie in the in the States, in Los Angeles, I would have my other director friends come and see the movie, I’d show them the movie, to see what they thought, and get their opinion, and sometimes they have great, sometimes they have terrible ideas but it all makes the movie better. And then they invite me to see their movie and I give them my opinion, and they can take it or leave it.

In Australia, we’re all very scared. I’ve actually gotten annoyed at some of my filmmaker friends here who don’t show me their film. They invite me to the premiere, but it’s like, I’m saying, that’s too late, invite me early on, where I might be able to help you make it a better film, you know? So that shows you very distinct difference between the social aspects of filmmaking in those two territories, those two countries.

Film still from “I Robot” (2004)

You are very successful in internationally, but how do you keep your Australian identity as a filmmaker?

Well, I’m not I don’t ever feel like I’ve had an Australian identity. I mean, I speak with an Australian accent. But I was born in in Egypt, my heritage is Greek-Egyptian. So, I don’t know what I am. I came when I was three years old. I know my parents were treated very badly by Australia, the very white bread Anglo-Saxon Australian culture, which, fortunately, we’ve left behind us a long time ago.

So, I think my ethos is more European than Australian or Anglo-Saxon or even American, you know? I grew up watching American movies and so my greatest influence is American cinema. But I also love European cinema as well, like Tarkovsky is one of my favorite directors. Luis Buñuel, is another one of my favorite directors. So you know, my real favorites tend to be, but I like Hitchcock as well, and Kubrick, of course, and so I’m very much an all-encompassing omnivore of culture. And the fact that I’m in Australia.

Look, don’t get me wrong, Australia, I’m mad at Australia right now because of what’s going on with our government. But it’s a great place to live and a great place to work. And the film crews are terrific here. The work ethic is wonderful here. And we make great movies. So that part of it’s great, but I’ve never really felt like I was 100% Australian.

I’ve always felt like an outsider, which I think is very much what’s depicted in my films, I think all my films are about outsiders partly because of my upbringing. I was in a country which didn’t feel like home, and that the culture of that country made me feel very much like someone who was not wanted, and someone who is outside from outside. I see my parents didn’t speak English very well. And they had difficulty because there’s a lot of racism about you, people like my parents. And so it was, it was a difficult upbringing, and all that stuff is in my work, because I’ve never felt like I’m in a secure place that I’m fully a part of. So that’s what it means to be an Australian, unfortunately. But it’s a good thing, in many ways, apart from what my parents went through, it’s a good thing. And I went through it too, because I feel like it’s shaped my work. I think it’s an identity that a lot of people understand, particularly, as people move around the world more and more, there’s more immigration, there’s more people from other cultures.

I mean, I totally get this world worrying. And I totally understand those people’s plight, and it’s all in my work. It’s not on the surface, but it’s all there underneath, it’s represented in other ways through, that’s what science fiction is so great at doing is, showing you something that is actually very socially relevant to today, but showing it to you in another context. And in some ways, you get a better understanding of it by stepping back and seeing it in a more objective way.

Yes, exactly. And is there any government funding for movies in Australia or not?

There’s government support, but it’s …, look, I was bemoaning this today, the arts are genuinely being murdered here right now. Unlike the UK where they’ve had $350 billion of support for theater, for music, for film, for everything in the last year since the pandemic started. Here, we’ve had none of that support, very, very little support. Except for the support that was rolled into everyone else’s wage that was supported at one stage in the original lockdown. Now in this lockdown, people are getting nothing. Businesses are applying to get some sort of money if they’re right on the edge of bankruptcy. And even they are having to wait and a lot of them haven’t yet received a single cent from the government. So we’re being treated very badly and the arts are being treated as bad as bad as anyone else. Of course, if you make a Marvel movie, or something, you bring a big blockbuster to Australia, then the Australian government gives you a very healthy, it’s called a tax offset. It’s like a rebate, a tax rebate. So, for every dollar that is spent, the production can get 40 cents of that back. But of course, that goes directly back to the big boys -Disney or Warner’s or whatever, overseas. So, they’re basically managing to make their big movies at a much lower price, you know, which is good, there’s nothing wrong with it. It’s good that, you know, it supports the industry, it means that the crews are working, cast is working, everyone’s working. And I’ve certainly benefited from the same structure with my own big Hollywood films. But I just wish that there was an equal level of support or a greater level of support for our own home-grown independent industry and right now, that’s very poorly supported, if at all.

Alex Proyas being interviewed by Diana Ringo from Indie Cinema Magazine

And how do you feel the cinema industry changed in this past decades since you personally started working?

Well, it’s completely different. It’s changed enormously. I mean, the fact that right now we can create our own virtual worlds and shoot our actors and put them into those worlds, it’s a huge move, step forward, into lowering the budget of the film, and enabling the imagination of the artist of the creative artists, a director and writer, etc. to do what they want, but not at the budget that you used to have to do with that. You can do it on a much lower budget, so that’s a really exciting development, that’s why I built my studio is to try and enable filmmakers of all levels from Marvel down to anyone in the low budget independent filmmaker, to do all this stuff at a lower budget, do it quicker, easier, better. And, therefore allow us to open up our imagination and not be limited by the logistics of filmmaking, which has always been the case, up until quite recently. As you write your script, you go, I can’t afford to do that, you get rid of that paragraph, and you write something else. Well, I don’t want that world anymore. I want the world where you come up with whatever you want on the page, and you can somehow manage to do it. And I think we’re, we’re approaching that world. And I think we’ll get there in the end.

Yes, it is indeed important to make new studios, as Disney makes movies which cost $200 million or more, it’s good to get back to somewhere more manageable.

I mean, they don’t care, they can afford to pay $250 million, and everyone gets paid a lot of money and who works on and fine. But I mean, I’m building an alternative industry to that I’m like, that’s fine. They can milk that cow as long as they like, until the superhero becomes out of fashion, which will happen eventually. In the meantime, me and many others, we’re building an alternative methodology because none of this works. It doesn’t work for anybody, right? It doesn’t work for the filmmakers. It doesn’t work for the finances. It only works for a very specific group of people who have those sorts of budgets and that distribution net, that they can put their stuff out to that many people to make that big profit back, from the big money that they put in. And it works for no one else. And this is the whole thing from production right through to distribution is we need to rewrite the rules in order to come up with an alternative. That means that independent filmmakers they don’t have to make billions of dollars. They just need to make enough for their film to make some profit for the finance, finance people. For them to go, you can you can do another one, right. And for them to be paid, so that they can feed their families and feed themselves and give themselves some time between each movie to sit at home and write the next script. That’s all that we need, what any young filmmaker really wants, but that’s doesn’t work in this in this world, you know. In this world, if you don’t plug into a big franchise, and then you come out of the big franchise, and you go, okay, what now, I’ve got to go and do another big franchise film. Well, it’s gonna be limited what you can do, because the way the big franchise people work and the reason they keep working with new young filmmakers all the time, is because as soon as you get to the point of being at all questioning or cynical about the process, or even wanting to actually direct the film, rather than just be a traffic cop and do your thing in a very small part of the production and let someone else direct all the action and come up with all the storyboards or whatever. As soon as you get to that point, they’re going to kick you out, and you’ll get the next exploitable person in through the door. And there’s a line of them out there who all want to do this stuff, of course. They’re going to go from making a $100,000 movie to being paid a few million dollars to direct something with all the toys and all the whatever. But it’s a trap, it’s a huge trap for people. And it’s not supportable. It’s not a sustainable industry from the filmmaker’s point of view. It’s sustainable for Disney. But everyone else is at the mercy of that – we’re all just cogs in the machine. We’re all just cannon fodder. It’s not a sustainable industry for individual filmmakers. As I encourage people, I said, the only sustainable industry is to build your own brand. Don’t go and build Disney’s brand for them. Build your own brand – that is the only sustainable industry.

Film still from “Gods of Egypt” (2016)

Maybe even create your own Disney, a better one.

It doesn’t even have to be Disney. Great, some people will have their sights set high. As I say, it just needs to be a way to make your films, do what you like, and, and be able to make the next one and feed your family. That’s all any of us really want.

Can you tell us also about your YouTube channel? When did you start using it? And how did you find these ideas for your content? For example, I like the “Dear Leader” videos very much.

Thanks. I just started mucking around with it just because it was a bit of fun. I do it all myself and I edit it all. And it’s just fun to do? I’d love to be able to use YouTube as a way to promote narrative short films, but it doesn’t work for that. What YouTube is good at is promoting short interview type stuff or presenter type things. I find it amazing to this day that sometimes I watch YouTube videos in horror, going, honestly, this thing has got 4 million views in like, one week. And it’s some girl getting a haircut, that’s really what the whole thing is. And I’m writing this stuff that I hope has got many levels of depth and philosophical and political aspects to it. And I get a few hundred views over a few months. And that to me sums up YouTube. That shows you what YouTube is good at promoting and what YouTube wants, and what the people who watch YouTube or the lion’s share for them, that’s what they want. So, it doesn’t work for people like me. But I had to discover that through doing it. For me everything is an experiment. Every film I do, every project I make, in a way is experimental because that’s the mindset that I have. And I like to learn new things. I don’t want ever to get to a point where I go, I know how to do that. That’s easy or whatever. Or abandon it because it’s too hard. I want to learn and try everything. As soon as I work something out, I want to try something else. So, YouTube, for me was one of the experiments and continues to be where I put this stuff out there and I do this with my head when I see people getting their haircuts and getting 4 million people watching them or someone playing a video game to a million people watching them. It’s hilarious. You know, what can I say?

Well, I think you get a black mark on your work if the algorithm doesn’t like your work. If it sees people are opening, watching your thing and then they just lose interest straightaway, on your statistics, or whatever they’re called. The algorithm just decides, now we’re not going to promote this, this project.

But hell, if there’s a lot of people out there wanting to see someone get a haircut. Or I mean, the other thing I’ve never really felt comfortable about doing is leveraging off other established work, you know, like, literally, I know if I put a video out saying “Marvel movies suck”, you know, “Proyas goes off on Marvel movies, and tells you how much he hates them”. And that would probably get a million views. Right? But it’s not what I want to do, I don’t want to do that, YouTube works on antagonism and divisiveness and conflict. Real conflict as opposed to dramatic narrative conflict. And also if I mentioned things that people want to hear words like Marvel, that they want to hear, then people are going to be a lot more interested in it than if it’s some weird little philosophical film by a guy that some people have heard of, but most people don’t know, have no idea who I am. And, it’s just the nature of the beast, human nature, you know, what can you do. But at the same time, I’m building a dedicated streaming platform at the moment. That’s one of my other projects.

And amongst all my other projects, it will be probably a year before it’s online. But we are trying to bring short film content together into programs or festivals or whatever we want to call them retrospectives, in some cases, similar content, bring it all together and promote it on this streaming platform. So, people can view these specific programs of content that are curated by me, and probably some other people as well. I’ll try and curate as much of it as I can. Some of it will be my films, mostly it will be other people’s films. And we think it might be a great viable alternative to YouTube, where basically YouTube is like what the algorithm wants you to watch is what gets promoted. Whereas with our platform, it will be well, what we believe is really great content. That’s all we want you to watch, you know.

Films of worldwide filmmakers, or of only Australian filmmakers?

For everyone, worldwide. That’s the beauty of the internet is it doesn’t have to be, it will be more genre specific. It will be science fiction, horror, fantasy, etc. But it’s worldwide, so anyone can contribute content.

VIDIVERSE – new platform for independent filmmakers

Do you have a name for the platform already?

It’s called VIDIVERSE, but it won’t be live probably for another six months at least.

Any advice on how to not get depressed in today’s times; how to keep yourself motivated, how to work and live life?

I think obviously, your family, my family is the most important thing and staying connected with your family. If you don’t have a family, as many people don’t, and some people are distant even with their families, or they can’t connect with them, because they are locked down in their own bubble, you know, their own isolated bubble, etc. I feel like, I mean, for me, and all I can say is what works for me, is continuing to create stuff, finding a way to create stuff. And I’ve always used filmmaking as a form of therapy, anyway. From the very beginning, I remember, when a very good friend of mine died, he’s like my brother, not a real brother, but he was like as good as a brother. The first thing I wanted to do is to make a film, because, to me, it was like, I could lose myself in that film, in that process of creating something and not think about, you know, the death of my friend. And so, to me, creating is a very important part of staying sane. But as the world gets more insane, continue to create.

I’m making another short film in the next few weeks, which is difficult, because now we can’t work with people in other parts of Sydney, we can’t physically work together. I’ve got two actors who are in different parts of Sydney, and I’m going to direct them through Zoom. They’re going to have to film themselves on your phones, or cameras or whatever we can get to them. And they’re going to send me the material, we’re going to edit, based on a script that we’ve written on a concept that we have.

And for those two actors as well it’s a way of staying sane by just doing something. Both of those actors, they haven’t got any acting work, because of obvious reasons, but also their day jobs. Most actors in Sydney and probably all over the world, most young actors, their day job is often working in a restaurant, or a cafe or hospitality. And that’s all been shut down. We can’t go into restaurants at the moment. So, a lot of them have lost their day job as well. So they’re very tough circumstances for these people, as it is for all of us. I feel like it’s a life preserver, to stay sane – just keep creating. I think the only thing I can offer so very much but it’s the only thing I can suggest to people, you know.

You’re very much right. Do you have something to tell about working with actors?

Well, every actor is different. Of course, there isn’t one standard technique to work with actors.

You know, the interesting thing, a lot of people ask me about the technique of working with actors, when I’m doing visual effects, where sometimes they’re reacting to something that isn’t on the set that they have to imagine, and I like to show them a lot of shaded graphics, or drawings or something, to give them an idea of the world and the situation they’re going to be in.

But actors are like kids and that is they use their imagination as a very important tool, for an actor as it is with children, and they very easily seem to embrace that way of working. So, it’s not like I have to really do much beyond what you normally do with actors.

And as I say, every actor is different. Every actor needs different techniques and different methodologies. And there’s many different ways to work with actors, for sure.

Film still from “Dark City” (1998)

Do you do a lot of takes when shooting?

No, I don’t like to do a lot of takes. I don’t see the point. I don’t understand why you would do a lot of takes. I know filmmakers, like Kubrick, who’s my great inspiration. He was famous for doing a lot of takes, but I suspect he was doing them for reasons to maybe annoy the actor. To get something out of the actor, which can work as a technique. I mean, I played games with actors as well, but I have their full cooperation.

I feel like if you’re going to be angry to an actor, or put them through some sort of torment to elicit some performance, I feel it’s it has to be with their cooperation. So I think it’s an agreement you have to make early on in the process, to say “I’d like to try this technique as a director”. If I feel like it’s with the right person? Is that okay? Will that help you? At the end of the day, I’m trying to help them, so I don’t like playing cruel games with people for no reason. I think it’s all without their understanding of what’s going on. I think that’s, that is cruel, you know.

So, I suspect Kubrick might have been in that same situation. But the other thing with Kubrick is that he being the perfectionist, I mean, we’re all perfectionists as all directors are perfectionist, which is why I feel like, that’s probably the reason why he has that reputation. Because if you do 10 takes of someone walking down a hallway, to get it right, I can kind of relate.

If you do 100 takes to someone walking down a hallway, there is literally no reason other than to piss that actor off, and piss everyone off, quite frankly. Because if you haven’t worked it out by take 10, there’s nothing you’ll be able to do. If it’s outside and you have no control over the lighting and you’re waiting for a cloud to do a certain something or whatever or the wind’s blowing in the wrong direction, then I understand.

But to do a 100 takes on a soundstage of someone walking down a hallway, which is the famous “The Shining” thing with Jack Nicholson. There is no other reason other than he was Kubrick and Nicholson probably was completely in the loop. They were trying to get a certain tension out of him that he wasn’t getting. And this was a way to channel that tension. So that’s the only thing I can I can assume was going on in that instance. We are in a controllable environment where things don’t often go awry. If I don’t get it in two or three or four takes, it’s all downhill from there, it’s not going to work.

Usually three, four or five takes, we get it. And then maybe we’ll try something completely different. I’ll throw something at the actors that says, try it like this, just to sort of see some other version of it. And we’ll go, that was interesting, or that was terrible, I like that better. If we get something great out of it, usually it’s that spontaneity, that is the best thing, the energy that I like, is the spontaneity that comes with the early takes. Now that we shoot digital, I often don’t even rehearse, like, I’ll often just go – “let’s work out our marks or focus, etc., okay, let’s shoot it”, you know.

The actors know what they’re doing. And that throws the actors into the deep end. And then they are really engaging with the drama and each other. And they’re not controlling themselves, they’re literally going with their instincts, their gut instincts, on the first take.

And I find that take one, it’s a bit of a shamozzle, it’s interesting, and then take two is usually where the real gold emerges. So more and more, that’s the process I’ve been employing with my actors and that’s early takes, few takes, and then do more if something has gone completely wrong – focus is no good or whatever.