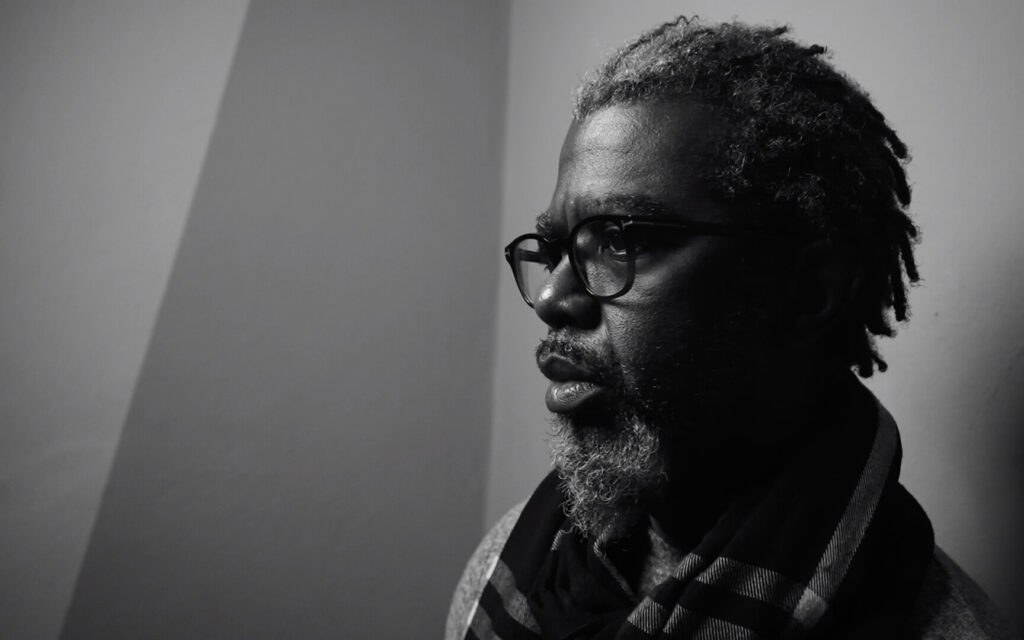

In this exclusive interview, director and writer Darrell Bridgers delves into the profound psychological exploration of love and loss in his latest film “Zeke”, offering insight into the emotional depth and complexity that defines the story. Bridgers reveals how his background in psychology and law helped shape the character of Zeke, a man grappling with late-life epiphanies. Bridgers also shares insights into the challenges of creating a compelling narrative with a single character, his inspirations, and the decision that led him to take on the lead role. He touches on the universal themes of love and loss, the influence of his New York City environment, and his future plans to expand “Zeke” into a feature film, exploring broader themes of the human condition.

Indie Cinema: In “Zeke,” the central question is whether the character has ever been in love. How did you approach the complexity of this question in the storytelling process?

Darrell Bridgers: On the surface, the question seems like a simple “yes” “no” type of query. However, the answer is much more complex when one really considers the concept of love and what that word actually means. Rather than give a typical response therefore, I thought using imagery through storytelling would best depict the notion of love. However, even with the storytelling device at his disposal, the main protagonist finds the task of defining love almost impossible. In the end, he can only describe the effects of not fully embracing love. He resigns himself to his limitations and resigns himself to the only answer that he can muster, which is describing the antithesis of love with “I am not sure I know what love is, but I sure know what love ain’t.” For me, that inability to directly define love is the most poignant testament to the power of love and being in love. I liken it to the inability to define God, which makes sense, as the very definition of God in many cultures is love.

IC: “Zeke” is a monologue-driven film. What challenges did you face in creating a compelling narrative with just one character speaking directly to the audience?

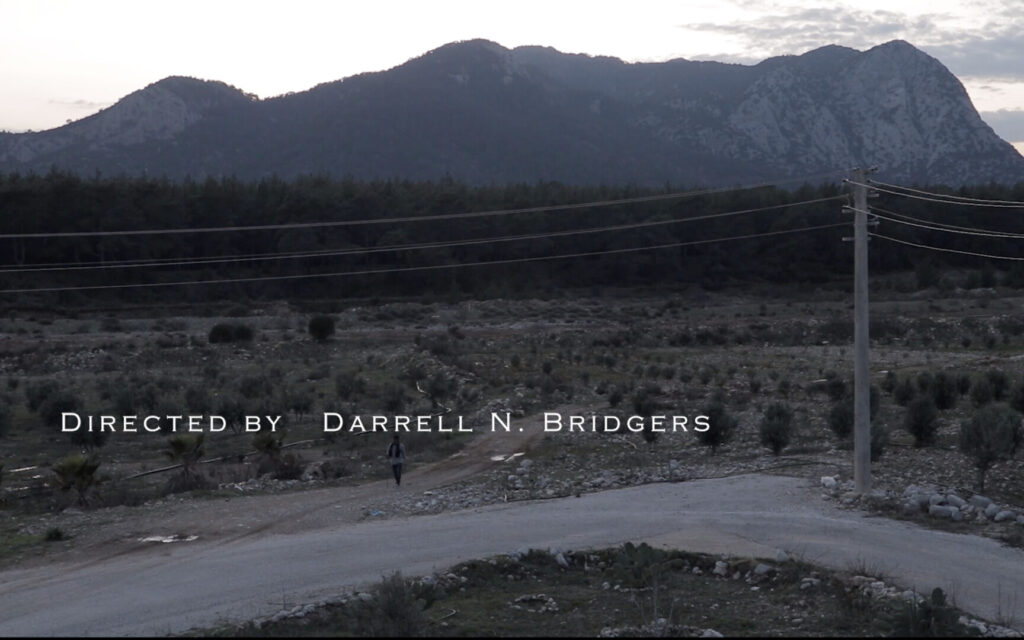

DB: I find the topic of love to be very personal and almost quiet. But, as anyone who has ever been in serious romantic relationship can attest, feelings of love can also be intense and somewhat action driven. So the main challenge was tempo. How could I convey all the intimacy and tragedy of love using one quiet voice and without being so cliched that the story comes off as boring. My answer that dilemma was to use various techniques to convey the right intense and quiet mood (such as lighting, black and white imagery, a solitary figure in a wide-open landscape and blues music) while keeping my intended audience engaged, which I hoped to do by employing a southern accent which I personally enjoyed listening to as a child whenever my grandmother would tell me stories.

IC: How did you decide to not only write and produce the film, but also play the lead role?

DB: Frankly, it was serendipity. As I was experimenting with lighting and testing different settings for the monologue, I found myself crying during each take. My emotional response to the story was so visceral, that I thought my raw interpretation would much more compelling to an audience than an actor trying portray the genuine feelings that welled up in me naturally as the author of the story.

IC: The film explores the idea of an epiphany that comes too late in life. What message do you hope the audience takes away from Zeke’s realization?

DB: Be bold in life and in love. I know that almost sounds like the beginning of a trope, which I was trying desperately to avoid. But our human reality is that we only have one chance at this version of ourselves so we should experience as much of this life as we can, both the good and the bad. I have a tattoo on my arm that says…”’cause you just get so many trips ‘round the sun.” It is a lyric from a song by Kasey Musgraves. It reminds me of our limited time on this earth as we only have a limited amount of trips around the sun in this life. It is the imagery of taking a trip around the sun (which is how I measure my life rather than in years) that keeps me focused on experiencing everyday as a journey. It is this idea of living in the present moment and not missing any important parts of the trip that I hope people take away from Zeke’s experience.

IC: Given that “Zeke” is based on one of your short stories, “Interview with Zeke,” how did you adapt the story for the screen?

DB: I wanted a spaghetti western type of feel so I added scenery shots at the beginning and end as old blues music throughout underscoring the dialogue.

IC: Were there any significant changes you made during the adaptation?

DB: I am not a professional actor so I had to use props (the cigar and the tea) to help me slow down and portray the character’s mood.

IC: How did your background in psychology and law influence the development of Zeke as a character and the themes explored in the film?

DB: I think, as humans, we are driven to connect with each other through communication. One of the worst and best states we can experience in my opinion, therefore, is solitude. If we are using solitude as a way to reflect on our place in humanity then it can be a rewarding experience but if it results in our exclusion from human interaction, then it is often a tragic state of being. I will explain using a definition of solitude I found as I was preparing for this interview:

“In psychology, “solitude” refers to a state of being alone, which can be a positive experience when used intentionally for reflection, self-discovery, and recharging, allowing individuals to engage with their own thoughts and emotions without external distraction: however, if not managed well, it can also lead to feelings of isolation and loneliness, highlighting the importance of finding a balance between social interaction and personal time alone.”

Zeke is actually skirting both experiences in his solitude.

In the monologue, I try to touch on themes of family, religion and sexual orientation in a way that is poignant without being offensive. I think having a legal background has trained me to walk this very fine line and certainly helped in developing Zeke’s character.

IC: You mention that Zeke’s story is influenced by factors like religion, ethnicity, family, and community. Could you elaborate on how these elements shape Zeke’s understanding of love and identity?

DB: Zeke, like all of us, is a product of his environment. I think we all have an innate sense of love and fairness. However, our social constructs of religion, ethnicity, family and community, often compete with, and oppose, those natural inclinations and desires. Zeke struggles with those imposing forces his entire life and in the end this internal conflict inhibits him from affirmatively being able to define love.

IC: As a debut filmmaker, what were some of the most surprising or challenging aspects of bringing this story to life on screen?

DB: The most surprising aspects of bringing this story to life on screen had to be hands down the ability to see my vision unfold in front of me in a way that an audience could relate to. It is not easy to convey what is in your head on paper. It is even harder to record your thoughts in a visual medium and make it accessible to third parties that don’t share the same internal filters. I admit that I struggled with sound quality a bit but was able to overcome that with the aid of post-production engineering. Once that problem was resolved, my vision really came to life on screen.

IC: How did the style of interviews in “When Harry Met Sally” inspire the format of “Zeke”?

DB: “When Harry Met Sally” is one of my favorite films. My original idea was to conduct a series of interviews on the same topic using the format of “When Harry Met Sally” that touched upon more modern themes of race, gender, religion, family, etc. My ultimate goal is to create a feature film using elements of Zeke, which includes other characters being interviewed.

IC: What elements did you adapt or reinterpret in your film?

DB: I used oral story telling as the medium to convey my message in the short film instead of live reenactment of the story. I also wanted the emotion of the present state of the main protagonist to be the focal point of the audience rather than the story leading up to his decision to choose his current lifestyle. I thought this was a bit more realistic since we typically meet people after prior events have shaped their lives.

IC: This is your first film project. How did your experience as an author help you in the transition from writing fiction to directing a film?

DB: As the author, I did not have to explain my vision or rely on someone else’s interpretation of what I hoped to convey. The challenge that I faced was not having any formal training as a director. In future projects, I would probably collaborate with others that have a bit more experience in directing films.

IC: Your collection, “Dark and Lovely, A Collection of Short Stories and Poems,” includes “Interview with Zeke.” Can you share more about this collection and how it reflects your interests as a writer?

DB: The collection consists of both poetry and short stories. The poetry is more romantic and light. The short stories all have a bit of a dark twist, like George R.R. Martin’s (“Game of Thrones”) Story, “The Pear Shaped Man” (1991).

My writing generally (and Interview with Zeke specifically) mixes both elements of romance and nostalgia with a bit of a Hitchcock-like twist. Specifically, I like to take everyday objects and quotidian themes and reinterpret them from a macabre perspective.

IC: What was the most rewarding aspect of seeing your written work transformed into a visual medium?

DB: I can only liken the experience to taking an image in a photograph and reproducing the same image with one’s hands in a three-dimensional sculpture. Though they both originate from the same base, the expression is completely different and becomes two distinct creations. By way of another analogy, I have experienced a similar sensation of newness when switching between both sides of a reversible jacket.

IC: How do you balance your career as a practicing attorney with your creative pursuits in writing and filmmaking?

DB: I started writing because of the law. I was representing myself in litigation and I had to write thousands of pages of briefs supporting my arguments. During the process, I realized that there is a lot of creativity that goes into arguing for one point of view over another. In order to convince a jury or a judge to adopt a certain point of view (within the strict bounds of the law), the attorney must engage in the art of storytelling to create a space that will afford the listener the freedom entertain concepts that may be foreign to their way of thinking. Once the attorney has achieved that, then influencing outcomes becomes much easier. Since that experience, I have used creative writing and now filmmaking as a way to decompress from long periods of technical analysis and help be make better sense of my days. Essentially, I write in the early mornings before starting my days, which for me is the most creative period as most of the world is quiet and I can focus my thoughts.

IC: When was the moment you realized that you wanted to make films?

DB: After I finished representing myself in the aforementioned litigation, I realized that I had developed some technical writing skills and had become somewhat adept at storytelling, so I decided to write a book, which will be published in the coming weeks. “Ripple of Hope: From the Boiling Frog’s Perspective.”

IC: As someone who has lived in New York City, how has the city influenced your work, both as a writer and now as a filmmaker?

DB: New York is truly a melting pot and there are so many cultures and points of view represented here that it is impossible to not encounter aspects of life that challenges our sensibilities. You can actually feel the energy of the people around you. It’s almost as if the City has a pulse. Accordingly, there are so many avenues for expression in a place like New York City and so many people will to help and participate, that it is easy to take risks and be somewhat vulnerable when it comes to artistic expression.

IC: What are your future plans as a filmmaker? Are there any other stories from your collection or new ideas that you’re planning to bring to the screen? Are you planning on making a feature film?

DB: As I stated earlier, I plan to make a feature film of a longer version of Zeke, perhaps with other stories a la “When Harry Met Sally.” I am currently in talks with a couple of Turkish filmmakers to adapt the story to the Turkish culture. I would make that as an independent filmmaker as well. The other story that I would like to bring to the screen is from the book I mentioned earlier, Ripple of Hope: From the Boiling Frog’s Perspective. Once it is published, will reach out to Netflix and other similar companies to see if they would be willing to take on the project.

IC: “Zeke” delves into complex themes of love and self-discovery. Are there other themes you’re particularly interested in exploring in your future creative works?

DB: I would like to explore all aspects of the human condition. My current novel,

Ripple of Hope explores themes of family, racism, redemption and forgiveness.

IC: You mentioned that you hope “Zeke” will encourage audiences to contemplate their own experiences with love. Have you received any feedback from viewers that aligns with this goal?

DB: The most interesting feedback that I have received so far is why I chose a storyline whose central figure was struggling with his sexuality as he was contemplating love, when I myself identify as heterosexual. For me, the question is a testament to the power of the concept of love. It transcends gender, sexuality, age and race which I consider secondary considerations. I wanted to express the concept of love from a perspective that was not my own to demonstrate the universal application of love, regardless of one’s cultural, physical or social constraints.

IC: How do you think the film’s message about love and self-realization resonates with contemporary audiences, especially in a time when discussions about identity and sexuality are more prominent?

DB: I understand that there are countless films and songs about love and self-realization, which makes this topic somewhat tricky to navigate as finding fresh perspectives can be challenging. However, I don’t think the themes of love and self-realization ever get old. There are as many expressions of love and self-realization as many there are people on the Earth, which is precisely why film and music focusing on these themes abound. The key is to find a message that resonates with the author and the right audience would gravitate towards it sort of like “Field of Dreams”. “If you build it, they will come.” If you believe in Proustian’s theory of unconscious memory, which I do, then most of us have an ephemeral concept of love ingrained in our psyche, which we readily tap into whenever we are so moved by certain sensory triggers, which is more relevant than ever at a time when discussions about identity and sexuality are more prominent.

IC: What do you think makes Zeke’s story universal, despite its specific context of an elderly man’s reflection on life?

DB: The concept of love itself, especially unrequited love, is universal and timeless. I refer back to the poem by Alfred Lord Tennyson, “’Tis better to have loved and lost than never having loved at all.” Ironically that poem was a tribute to Tennyson’s close friend Arthur Henry Hallam, who died suddenly at age 22 in 1833. Zeke’s story in its broadest terms is a contemporary take on that old adage.

We all long for that special connection with someone or some animate object to express ourselves and to share our common experience with, whether it’s an elderly man or a newborn infant, the need is the same and I don’t believe it ever changes.

IC: How important was it for you to maintain authenticity in Zeke’s voice and experiences, given that he represents a composite of real influences and challenges?

DB: Maintaining authenticity was paramount in telling the story, otherwise it would be perceived as contrived or worse pandering to current sensitivities relating to sexual identity. Zeke’s experience had to be cathartic to both the storyteller and his audience. That was part of the reason I decided to be the principal actor of the film. As I alluded to earlier, the greatest gift to humanity is the ability to communicate and hearing my own voice communicate Zeke’s near miss at the opportunity to experience love was absolutely cathartic. I could truly feel the pain and fear.

IC: Looking back at the entire process, from writing the short story to completing the film, what has been the most significant lesson you’ve learned as a storyteller?

DB: Filmmaking is a lot more daunting and time intensive that I ever could have imagined. I am glad I did not think this process through before I started. Allowing strangers a glimpse at one’s vulnerability can be scary and exhilarating all at once. I had the same experience when I scuba dived for the first time. Was I scared? Yes. Would I do it again? Hell yes.