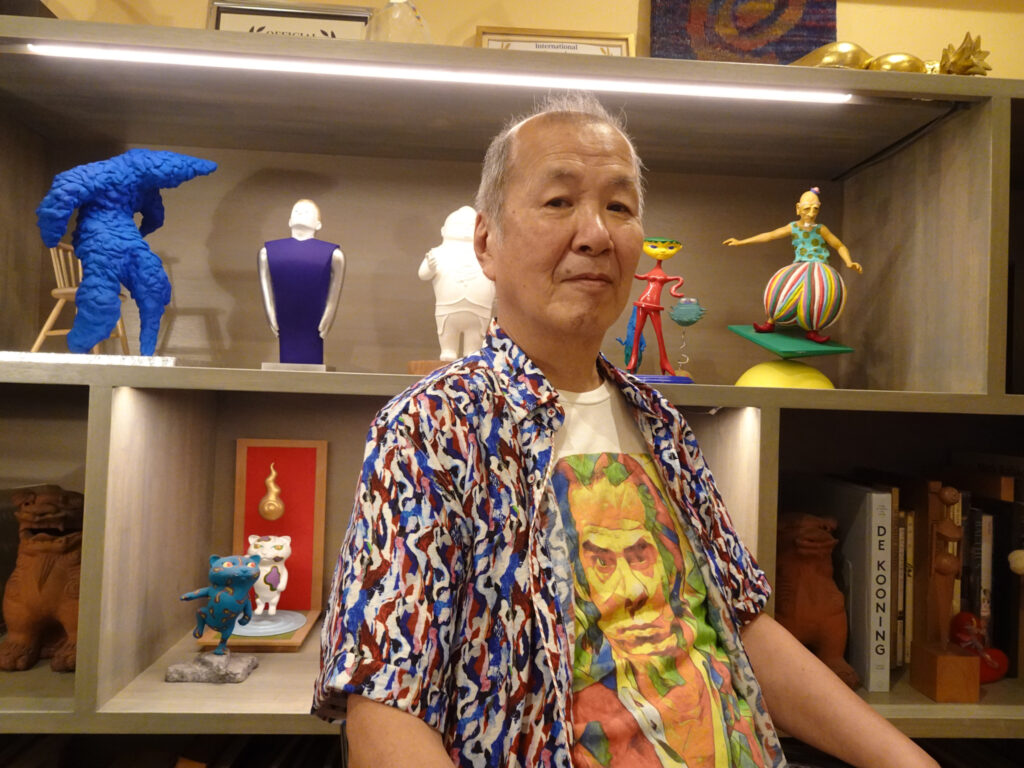

In this exclusive interview for Indie Cinema Magazine, we talk with Kazumi Shimizu, better known as “Shimizu K,” to discuss his latest short film, HOME. Having transitioned from a long and successful career in film promotion, working with major Hollywood studios and directors, Shimizu has now established himself as a filmmaker with a distinct philosophical vision. His latest project, HOME, a nuanced exploration of family dynamics, delves into themes of communication and isolation, while leaving much open to the viewer’s interpretation. Following the success of his debut short film, SLEEPING, Shimizu shares insights on his creative process, his transition to directing, and how his experiences in the industry have shaped his unique storytelling approach.

Indie Cinema: “HOME” paints a vivid picture of a seemingly ordinary family dinner that takes a dramatic turn. What inspired you to create this narrative, and how did you approach balancing the ordinary with the extraordinary?

Kazumi(K): Everyone is shaped by countless influences from the past. I wasn’t inspired by any specific event or moment when creating this story. Instead, I began by contemplating communication within the smallest community—a family. I started questioning what communication is, whether people naturally engage in it daily, and whether they even desire to communicate. That was the starting point for this story.

IC: You mention that the ‘Home’ itself symbolizes an individual’s mosaic-like thoughts. Could you elaborate on how you translated this concept visually and thematically in the film?

K: Understanding something involves constructing a narrative through logical steps. The characters engage in conversations that reveal their personalities and gradually move the narrative forward. The scene represents an attempt to grasp reality through conscious and objective perception. However, humans are not inherently conscious beings. Actions and thoughts often arise without deliberate reasoning. Even during conversations, the focus isn’t solely on the topic at hand—other thoughts drift in and out, passing through the mind as the dialogue continues. My cinematic expression is centered around this concept.

IC: The addition of the daughter’s classmate and an elderly figure at the dinner table introduces interesting dynamics. How did these characters influence the overall narrative and the family’s interactions?

K: What does it mean to communicate? Expressing one’s feelings and thoughts does not necessarily achieve communication. How much effort do we make to understand others? In the dinner scene, everyone is engaged in the shared act of having dinner, but there is no real conversation. We don’t understand why the elderly figure nods while looking at a painting, or what the daughter is trying to explain through her mime gestures. The father, observing them, remains an enigma. The boy moves around the room—why is he doing that? In our daily lives, we exist beyond understanding. We live in a world where comprehension, even if sought, is often unattainable.

IC: Your film leaves much to the audience’s imagination, especially in its depiction of familial relationships. What do you hope viewers take away from these open-ended aspects of the story?

K: The audience is diverse, and so are their impressions of the work. Some will view it favorably, while others may critique it. All of these opinions are valid because what someone feels is their truth. The impression of a book read in youth can differ significantly from the impression formed when rereading it in old age. Realizing the depth of thought behind something once overlooked is a common experience. I am merely the first member of the audience for this film. My main concern was whether it could hold the viewer’s attention for 20 minutes, as with my previous film, “SLEEPING.” With “HOME,” I aimed to sustain a sense of unease or thrill throughout. If that feeling comes through, the film has served its purpose. In fact, I’m more interested in hearing how others interpret it.

IC: Having transitioned from film promotion to directing, how has your background in promoting major studio films influenced your approach to filmmaking, particularly with “HOME”?

K: Entertainment films, even when their endings are predictable, must maintain elements that keep the audience engaged throughout the process. If that engagement falters, the audience disconnects. Film promotion is about making a large, diverse audience want to watch the movie. It’s about facilitating pre-communication between the audience and the film. My work is an art movie, and whether people will find it interesting is something I can’t predict.

IC: Your previous work, “SLEEPING,” was well-received in various film festivals. How did the success of “SLEEPING” influence your approach to “HOME”? Were there any lessons or insights from your first film that you applied to this one?

K: As with “SLEEPING,” in “HOME,” I wanted to express that consciousness is not fixed but constantly in motion. In the previous film, since there was only one character and the setup was relatively stationary, I used a combination of fixed and handheld cameras, which worked well. I initially followed the same approach in “HOME.” However, with the increase in characters this time, I aimed to more clearly convey the movement of consciousness, so I proceeded with mostly handheld shooting. Additionally, given the extremely tight schedule and the fact that I often handled the set design independently, I learned a great deal about time management and delegating tasks. I plan to apply these lessons to my next project.

IC: You’ve worked with Hollywood heavyweights like Martin Scorsese and Tim Burton in your promotional career. Do you have any memorable moments relating to these collaborations you would like to share with us? Did these experiences affect you as a filmmaker?

K: Throughout my career, my role was to develop PR strategies for promoting films. Specifically, I was responsible for the creative direction of Japanese trailers and posters and the planning of promotional concepts. Many of these projects involved aligning the promotional plans with Hollywood strategies, so I didn’t interact directly with the directors except during their promotional visits to Japan. However, one of the most memorable experiences from my early years was working on Martin Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver.” I was astonished by his immense talent. I believe the film’s ending depicts the protagonist’s dying vision, and it was a profoundly influential film that revealed the bleakness of America at the time, where dreams, hope, and trust were absent. Tim Burton is another director I admire greatly. “Mars Attacks!” was filled with homages to his favorite B-grade sci-fi films, but it was performed by an all-star Hollywood cast. The film showcased the depth and versatility of Hollywood. Both experiences reinforced the notion that in cinema, anything is possible.

IC: As a member of the Aging Filmmaker Club, how does your perspective as a senior filmmaker inform your narratives, particularly in how you depict generational dynamics within a family?

K: From a young age, I was captivated by countless films, and it was then that I began to aspire to make films as an older person. I may be a slower developer than most. However, this extended time allowed me to read many books, particularly those on C.G. Jung, philosophy, Buddhism, and avant-garde art, and to watch numerous films. These experiences have undoubtedly influenced my work as a filmmaker.

IC: In your director’s statement, you question whether humans are inherently designed to communicate with each other. How did this philosophical question shape the interactions between characters in “HOME”?

K: I don’t view communication solely as an interpersonal issue. My films explore the communication between characters and contemplate whether the depicted events could represent the thoughts within a single individual’s mind. In my view, the fleeting, ungraspable thoughts that emerge are part of the communication that occurs within a person. I am interested in exploring whether we are communicating with ourselves and what it means to do so. The interactions between the characters serve as a representation of this idea.

IC: Your film explores the concept of coexistence within a family. How do you see this theme resonating with contemporary audiences, especially in today’s fragmented, fast-paced world?

K: I hope the film sparks questions about what it means to communicate within the smallest unit of a community—a family. What is communication in the first place? And do we ever communicate with ourselves? If the film prompts these reflections, it has served its purpose.

IC: Given your extensive experience in the film industry, what are the biggest challenges you’ve faced as a director, and how do you overcome them?

K: This film is a personal project, so it cannot be compared to my past experiences in commercial filmmaking. The biggest challenge was securing funding on my own. In the end, I managed to complete the film on a low budget, thanks to the help of friends and acquaintances. I was fortunate that the concept of the film resonated with a wide range of people, from university students in their 20s to professors, traditional instrument musicians in their 40s, and executives in the film industry in their 60s.

IC: As you continue to make films, what themes or stories are you most interested in exploring next? How do they relate to your previous works, “SLEEPING” and “HOME”? Are you planning on making a feature film next?

K: My next project will likely revolve around the important theme of “Where does reality lie?” One of Buddhism’s essential teachings is the “Emptiness of inherent existence.” This concept will be a central focus of my exploration.

IC: The film industry is rapidly changing, especially with the rise of digital platforms. How do you see the future of independent filmmaking, and where do you position yourself within this evolving landscape?

K: Today, everyone carries a smartphone, allowing them to create films whenever they want, and there are channels available to share these works with a broad audience. Half a century ago, making and distributing a movie was much more difficult. Although this era offers great convenience, we have yet to see the emergence of a revolutionary filmmaking movement. As someone who has been involved in film promotion and now creates art movies, I might be expected to provide insights on the future, but I cannot foresee it. I’m focused on understanding the present—how the world is now, where I fit into it, and what my existence means. Without grasping the present, it’s impossible to predict the future.

IC: You’ve worked extensively in both Japanese and Hollywood cinema. What do you see as the key differences in storytelling between these two cultures, and how have you integrated these differences into your own work?

K: Hollywood has led the global film industry, and other countries have learned from it. Of course, different countries have produced their unique films, but primarily within their own borders. When theatrical releases were the sole foundation of the industry and other media were absent, films reflected their native cultures. However, to survive today, media and films must appeal to a global audience. Culture is closely tied to a nation’s identity, and while it’s important to express a country’s unique culture, it’s also necessary to consider how that culture will be received globally. In other words, we should strive to make our culture resonate with the world. Such efforts might be worthwhile if we aim to take on a global perspective.

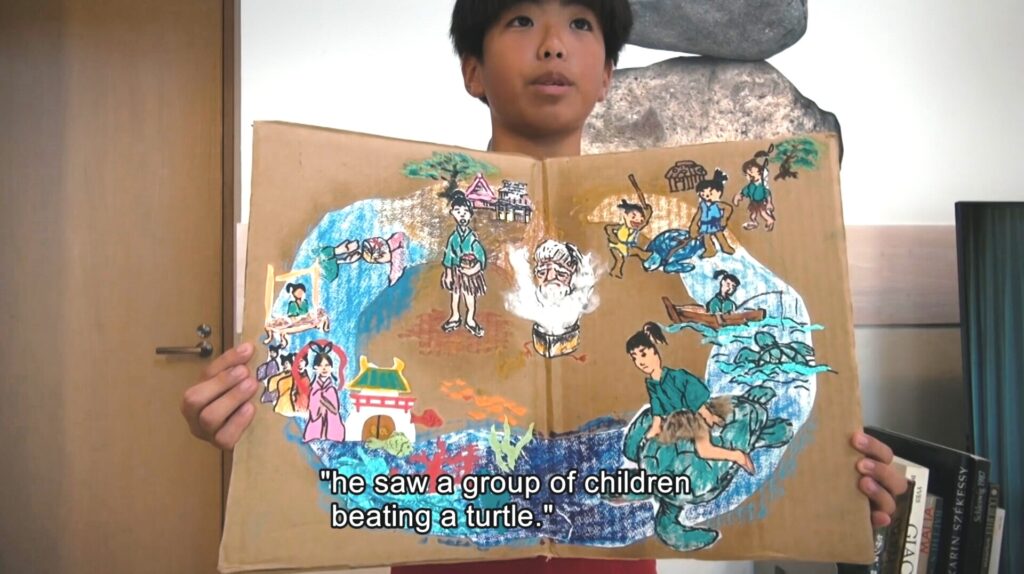

I am Japanese. In my film, there is a scene where a boy narrates an old story while showing a picture—it’s the tale of “Urashima Taro.” This is a story that everyone in Japan knows, from children to adults, and it has been passed down through generations. It’s an example of Japanese culture. Why has it been known for so long, and why will it continue to be passed down? Perhaps it’s because this story carries a warning for humanity as a whole. In the film, the father provides a Jungian interpretation of this story, which reflects my own interpretation. I see this interpretation as capturing a universal consciousness shared by people around the world. The topic of this question is vast, but it suffices to say that platforms like Netflix are bringing significant changes to film production.

IC: Finally, what advice would you give to aspiring filmmakers, particularly those who may be transitioning from other roles within the film industry to directing, as you did?

K: Whether you view filmmaking as a business or as an artistic expression is entirely up to you. However, consider whether your work will be like gum—chewed up and discarded—or something more akin to a fragrant marron glacé—savored slowly and fully appreciated. It’s a thought worth contemplating.