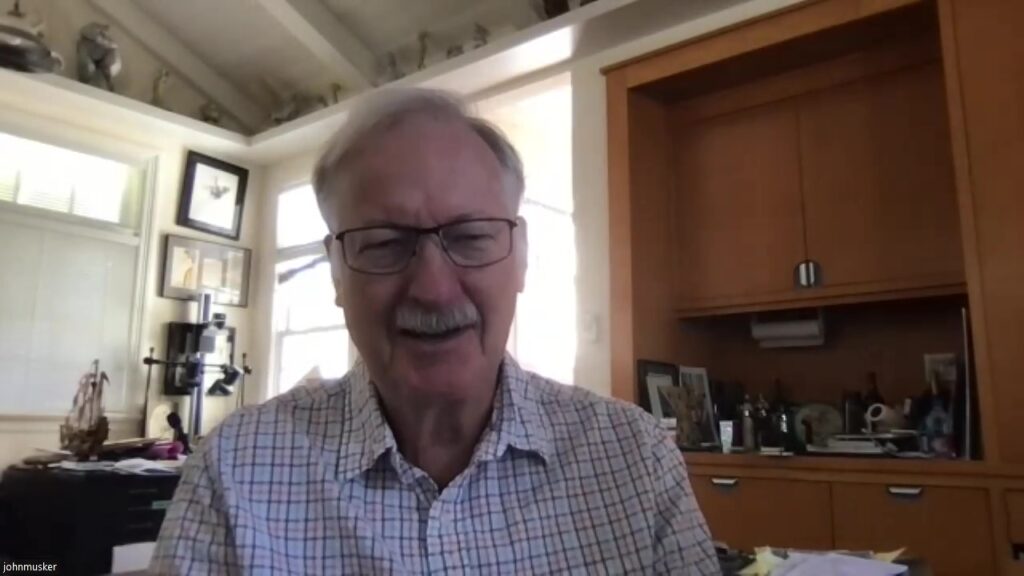

We are thrilled to present an exclusive interview with one of the most celebrated figures in animation, John Musker! Known for his legendary work at Disney on films like The Little Mermaid, Aladdin, and Moana, John has helped shape the landscape of animated cinema for decades. As he sits down with filmmaker Diana Ringo, the two explore the creative process behind some of his most beloved films, his long-standing partnership with Ron Clements, and the inspirations that have fueled his storied career.

Diana delves into John’s experiences transitioning from traditional hand-drawn animation to CGI, his thoughts on storytelling, and his approach to bringing iconic characters to life. With his insightful reflections on the ever-evolving animation industry and candid stories from his years at Disney, this interview offers a rare glimpse into the mind of a true animation legend.

Diana

We’re very excited that we will present your film “I’m Hip” at our festival – it is a wonderful picture with an amazing cat!

John

Yeah, it was a very silly movie. I worked for Disney for 40 years and worked on these big feature films, but I always wanted to make a short film. I went to CalArts for two years and studied animation there. I was part of their first character animation class. My classmates were John Lasseter, Tim Burton, and Brad Bird, who did “The Incredibles”. We made our little short tests—almost not even films—back when I was at CalArts.

And I always wanted to (throughout all my years at Disney) make my own short film again. I started as an animator and have always continued to draw, but hadn’t really animated. I started as an animator at Disney then took 35 years off from being an animator, and then got back to it with this short film. I really wanted to animate again. It was fun for me to do something very light. It’s based on the song “I’m Hip,” that I’d heard 30 years ago literally and always thought, “Oh, that would be fun to animate to”, and I had it always in the back of my head that it would be fun to do a film with that, so when I retired from Disney, I looked into getting the rights to that song, and I got the rights, I storyboarded it and my intention was to do all the animation myself, and I did – I did all the character animation myself in the film. I thought it would take me two years to do it, but it ended up taking four years. I was much slower than I was supposed to be, but I didn’t work on it full-time, I had fun doing other things. Then finally I completed the film last year, and it premiered at Annecy. Since then, I had it playing at various festivals, and I’m very happy that it will be at Prague Film Festival very shortly.

Diana

Yes, we were very happy to see the film. It’s wonderful, and when we saw who made it—such a legendary director!

John

Yeah, I started as an animator, and in the film, I dedicate the film to Eric Larson, was my teacher of animation at the Disney studios. He was one of the legendary Nine Old Men, he worked on “Snow White” and “Pinocchio”, he did Figaro the cat and Cleo the fish in “Pinocchio”, he did many other characters. In the 1970s, he was put in charge of training young animators at Disney. When I first came to Disney in 1977, I got to work with Eric, and he was the one who really taught me animation. Even though I had studied at CalArts for two years, Eric was the real teacher of animation for me, so I wanted to dedicate this film to him. He died a few years ago. He was a mentor not just to me but to a whole generation.

So yes, I’ve done these big, multi-year projects with hundreds of artists, and then I did this one with a handful of people. Of course, I thought because it’s just me doing it, it’ll go much quicker, won’t be quite like this big ocean liner that these features are. So, to do a movie like “Princess and the Frog” or “Moana”, it took, four years to make those movies. And so, I thought, I’ll do mine. But instead of doing 80 minutes in four years, I did my four minutes in four years. So I didn’t go any faster! It was just as laborious as ever.

I’ve had this strange career, that I did these big films with Ron Clements, where we wrote and directed a lot of these big movies. But then I enjoyed making this little film, and I have got a few others in my head would also like to do, that I am in the planning stages of. I’m hoping to animate a few more of these little ones that are personal projects for me and just fun to do. I have this little cottage studio here where I’m working away, and it’s a fun thing.

And yet, I still collaborate with people, because my favorite part of working in a big studio was the collaboration with other artists—they always enriched the movies. There’s a lot of ideas that came from other people. Even on this one, I had great help from visual development people, background artists, cleanup artists, and my sound effects editor. So, I was still directing on a smaller scale with these other people.

Diana

And do you have any pets?

John

Well, it’s weird. I’m Irish-American. My grandparents came from Ireland, and they brought with them all their allergies. My mother had terrible allergies. So when I grew up, I inherited them from my mother, so we never had pets around or anything like that. It’s funny, though, there’s a Disney Family Museum up in the Presidio in San Francisco, and it was built by Diane Disney, Walt Disney’s daughter. It celebrates Walt Disney, the man, but they also have various art shows there. They were having a show of paintings of pets by various animators, and they asked if I would like to participate.

I said, “Well, I have allergies. I never had any pets.” And they said, “You can draw your cat from your movie.” So I did. I drew a picture of my cat, but I wanted to make it kind of jokey. I did this little drawing of my cat, but I did it like the Sistine Chapel, where it’s me as God, and the cat is like Adam, and we’re touching fingers, as Michelangelo did. I sent it to them, and they said, “Okay, fine, we’ll print it up and put it in the show.”

What I didn’t realize was that they printed it up, so it was wall size, like 15 feet by 10 feet high—and they put it up at the entrance to this exhibit they were doing! So while people drew their dog or their cat, these nice little paintings, I had this big thing of this stupid cartoony cat up there.

My daughter, who has some allergies, has a pet dog—it’s a golden doodle, she brings it over all the time, and she’s not so allergic to it, his name is Potato. She calls it “Tato.” Tato was just here yesterday. Tato is a wonderful dog. We had a cat that sort of adopted us years ago. It wandered into our backyard—a kind of feral cat—and hung around. So, it became our pet, even though all of us, except for my wife, were allergic to it. Both my kids and I are allergic to pets. But do you have any pets?

Diana

No, but I expected some cat to model for the film!

John

(Laughs) Yeah, I have friends who have cats, there are some big cat fans, and my sister-in-law is a big cat person. They did a little modeling for me, but the rest of it, I somewhat invented.

Diana

What artists inspired you when making the film?

John

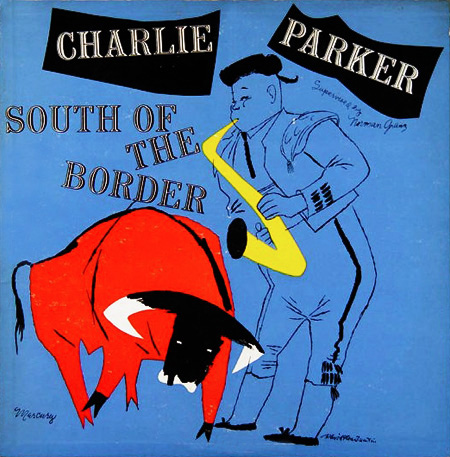

One of the big artists that inspired me is named David Stone Martin. He designed a bunch of jazz record albums in the early 60s. He did one after another of these beautiful designs—very linear drawings, beautiful black and white, sort of pen illustrations with flat planes of color behind them. Often, the colors don’t conform to the lines of the drawings. He was very much in vogue in the 60s, so a lot of these great jazz album covers have his kind of flat pattern things.

In this film, I wanted to adapt his style, so we have this kind of linear style with flat planes of color behind it that don’t always conform to those lines. In fact, even with the cat, sometimes we let the color of the cat extend beyond the lines, and in the backgrounds, there’s a linear drawing, but there are things that go beyond that. That was one of the inspirations.

Another one of Disney’s Nine Old Men was Ward Kimball – the great animator Ward Kimball, who animated characters like Jiminy Cricket and worked on “Pinocchio” but then on Alice in Wonderland, he did the Mad Tea Party sequence. And he was always, in some ways, the cartooniest of all the veteran Disney animators. I got to study with him briefly when I was at the studio in the 70s. He did the Cheshire Cat in Alice in Wonderland, as well as Tweedledum and Tweedledee. He was also very musical — the most musical of the Nine Old Men — so he was an influence on the film.

Now, on this film, I have actually embedded—I’m a caricaturist—and so for all these years at the studio, I have done caricatures of my fellow workers. I do them with my family members. Every year, I draw a Christmas card that has my caricatures of my family, and it’s some topical thing of what’s happened in the last year, or whatever. So in this film, I had these scenes where I had, in effect, extras—the cat would be wandering down a busy city street, and I had to put people in the street. So I thought, well, I’m going to put people I know in there, or that I’m kind of doing an homage to.

For example, on that big city street at the beginning, where they’re walking down, Ward Kimball is walking down the street. He’s carrying a trombone because he was a musician—that was his instrument. But I also put, on that street in the lower right corner, two people I worked with on Moana. I have caricatures of Taika Waititi and Lin-Manuel Miranda, who did Hamilton. They both were writers—both of the script and music on Moana—so I stuck them down there. But then I have my wife and I in the shot, and my son’s partner is in the shot, and I scattered people throughout, including Eric Larson, my mentor from Disney. He’s the fisherman who pulls the cat up out of the water. That actually is a metaphor for Eric saving my neck – it’s the studio, a few times, where they weren’t happy with my work. When I first started there, my animation was getting highly criticized, but Eric was my defender. He said, ‘No, no, he’s good. Give him another chance.’ So, there’s over 120 of these caricatures that are embedded in the film—again, people that no one would know. But for my amusement, in the scene when the cat’s in the movie theater with his girlfriend watching the arty French film—which is sort of a parody of Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville—it’s what they’re watching on the screen. But in the audience, the film buffs include Brad Bird, Henry Selick, who I went to CalArts with, and Jerry Reese, who directed Brave Little Toaster. And then there’s my sister and her husband, who’s a film professor in Chicago, and Jennifer Yuan, my layout artist. So everyone in that shot is someone that I know, and I just had fun with it.

When I premiered the film here in Los Angeles, I invited a bunch of people to a theater, and I made prints of those frames where the people appear, and I gave them prints of their part so they could have a little piece of the film.

So, in a way, that film, originally for me, was meant to be kind of a Valentine to hand-drawn animation. That’s what I grew up learning, and I love hand-drawn animation. I wanted to celebrate full animation—animation that’s on ones sometimes, you know, and isn’t limited. It’s fully animated. But I also wanted to celebrate jazz, because I’m a fan of jazz. I play the piano very poorly, and I play a little bit of jazz. But then it became this Valentine to all my friends and family because I stuck them all in the movie. So when I had this premiere, it was like a big party where all these people I knew got to enjoy seeing themselves very briefly—in some cases, literally for frames—in this film. But it was fun for me to make it this kind of hug to all these people.

Diana

That’s wonderful. What technologies did you use in making the film?

John

I animated the whole thing by hand, but I did it on this thing over to my left here. I animated on a Cintiq, a pressure-sensitive tablet. At first, I wasn’t sure if I was going to animate on paper or use software with one of these systems, so I decided to do a test. There’s an old American story you’re probably not familiar with, a legend called John Henry. John Henry was an African American man who drove rails, he laid tracks for trains, and the legend was about who could do it faster: the machine or John Henry. So John Henry was out there hammering away with a sledgehammer, and I think he defeated the machine.

So, I thought I’m going to take a scene and do it on paper, then take another scene (or maybe the same scene) and do it in the system on the Cintiq with the stylus, and see which I liked better. Well, I started to do some experiments by hand, and I was struggling because I couldn’t get good scans of my hand-drawn work. My paper drawings were coming out weird, and I didn’t like the resolution, the way they looked. Then I heard about this program called TVPaint, which is a French program. It’s a great program. Even though it’s called TVPaint, it doesn’t have much to do with TV. It’s sort of like Photoshop—you work in layers, and you draw in the system. I’m still drawing, but now am drawing on a tablet. I tried it out and loved that technique, so I used it for the entire film.

All the backgrounds were painted in Illustrator or Photoshop and imported. After Effects was used for compositing. I had this great girl, Talin Tanielian, who was my right-hand production person on this, and she composited everything in After Effects. Even though the backgrounds were drawn traditionally, they were drawn in Photoshop and then composited in After Effects and then assembled in Adobe Premiere – at the end of the line, everything moved into Adobe Premiere.

I asked the head mixer, who did Moana, The Princess and the Frog, Frozen, and all these films at Disney, if he wanted to mix my film, and he agreed to. I rented a studio in Santa Monica. He got a day off work, I paid him, and he mixed the film there. It was great having his expertise, adding sound effects to the track and all that. So, yes, I was taking advantage of digital tools I had, but at the heart of it were still the animation lessons I learned from Eric Larson 45 years ago. These lessons involved squash and stretch, communicating graphically, having strong silhouettes, having arcs that people can follow, volumetric drawing, and believable action that has weight. It was a celebration of that traditional thing, but using new tools.

Diana

I really loved it. It was hard to tell if it was drawn on paper or not.

John

Because of the look of David Stone Martin’s illustrations, he used watercolor in those washes, so Ken Slevin, who did some of the backgrounds, really used digital tools that simulated watercolors to give a kind of a splattered look to some of the backgrounds and a loose thing. And there was development work done by Claudio Acciari, a great Italian artist, who did some watercolors for me and things like that. In fact, he even scanned some of his watercolors, and we used some of the textures from those watercolor scans in the backgrounds because it just gave a neat, hand-drawn, sort of period look to it.

Diana

So its great that you’re embracing new technologies. And what it’s like to make your first independent film?

John

Well, it was interesting because I enjoyed it. The weird thing was, I started before COVID happened. I started mapping out the film, and I would invite people to my studio and show them the project. I’d ask, “Do you want to work on this or not?” and they said yes. I also produced the film myself, I didn’t really want to have to answer to anybody. I had a lot of creative freedom at Disney, but I really felt that I didn’t want to have to show it to anybody other than me to get approval for anything. So I paid for everything, and I paid all the people who worked on my film. I didn’t want to try to chisel free labor out of them, so I paid them—not as much as they would get paid at a big studio—but I did pay them.

COVID made it a little weird in a way though because I was retired and working in my studio, and then when COVID happened, it seemed like the whole world retired. It felt like everybody was retired. So the novelty wore off a little bit. I thought, “No, I want to be the only one retired,” or at least I wanted the world to continue outside my room. Yet, you know, people were cocooning in their own spaces.

It was interesting because I had to—I’m a fairly disorganized person—get more organized. At Disney, we had great teams of production people who really kept us on track. Half of those films couldn’t have been made without those people. But I had to become those people; I had to create a bit of a schedule. I didn’t want to burden myself too much with deadlines, and yet I had to figure out how to do this, get this done, and then get that done. So I was my own production manager in some ways, and Taleen was that too. That was a new thing for me, just trying to stay on track. Literally, every week when someone would complete something, I would have to write out a check for them and send it out. So I was the payroll department too.

That’s nothing new to anyone in the world of independent film, but for me it was, having been spoiled by this great infrastructure that did so many things for me, and you could just focus on these other things, I had to wear many hats. But it was fun. I liked bouncing back and forth between these different roles, so I enjoyed being an independent filmmaker. I’ve enjoyed certainly going to some festivals, showing the film, and seeing the work of other filmmakers. Over the years, I’ve enjoyed independent films—both live action and animation. I’m a member of the Motion Picture Academy, so we see the films that are up every year, both for animation and live action. There are some brilliant films. I don’t go to the huge live-action screenings, but after they’re whittled down to a smaller number—about 15 or so—I see those. I’m really in awe of so many of them.

It’s always a challenge, I know, for any filmmaker—live-action or animation—to pull together a team, find a grant, to find some money. It’s a struggle in that world, and I get it even more now that I’m paying the bills. But I really enjoyed it, and like I said, I’d like to do another one. The other ideas I have in my head are again music-driven, because that’s what fascinates me most about animation: the way it works to music. Although two of the things I’m considering are instrumental pieces – they have no lyrics, so the story can go in many different directions, so it’s a little trickier for me to zero in on the story because you don’t have the lyrics as a framework. But I like that too, because I can take it wherever I want.

With the film I just did, I really tried to work with the track, so I couldn’t lengthen the track or change the story content dictated by the lyrics. Now, with these other projects, if I decide I want a shot to be longer, I can make it longer. I’d still have to trim another scene, but at least I’m not bumping into a lyric that doesn’t make sense anymore. So I’m looking forward to that as a new challenge, because I didn’t have to face that on the last film. But I’ve enjoyed being an independent filmmaker.

But I’m still making films, because of my own nature, for an audience. Some people can make a film and say, ‘I don’t care if anybody understands it. If I like it, that’s all that counts.’ And I admire people who do that. But I’m not like that. I’m an entertainer and a storyteller, and I’m trying to communicate with an audience. If the audience looks at what I’m doing and they don’t get it, I’m disappointed because that wasn’t the intention.

However, I don’t like having that middle area of people saying, “Do this or do that or don’t,” or, “People may like this or may not like that.” I enjoyed not having to go through that gauntlet. Like I say, if I make another film, which I hope to do, I will again enjoy that thing—doing some things that I am amused by, even if other people may not find them amusing, or creating moments that move me. Some of my ideas may have a bit more emotion or drama—they’re not all just comedy. But it’s fun to just venture down these byways, even if they’re a little off the beaten path.

Diana

Yes, that’s very true. And how did you first start working in Disney?

John

I’m originally from Chicago, Illinois. I always drew as a kid—I always did cartoons and things like that—so I thought I’d probably go into that line of work. I’m a Catholic, and I went to Catholic school, so I was taught by nuns in my youth. Then I went to an all-guys Jesuit Catholic high school, and they had no art classes there. So, I was basically teaching myself to draw, reading comic books, and seeing Disney films. I got hooked on animation at an early age and thought I might want to be an animator, though my interest drifted away a bit.

I went to Northwestern University in Evanston, near Chicago, and I majored in English literature because the Jesuits had convinced me I shouldn’t use college as a vocational school. So I thought, well, I am going to major in English to force myself to read the great books of the world, including English literature. In the meantime, continue to draw, thinking I’d probably try to get a job doing cartooning of some kind, either in comic books or whatever. Then, when I was at Northwestern, Chuck Jones, the great Warner Brothers animation director—who did the Roadrunner cartoons, as well as the great Bugs and Daffy cartoons—came to speak. He showed a selection of his films, and they were amazing. He spoke very passionately about animation and said that he even as a 60-something-year-old, he still felt like he was learning things. That made a huge impact on me—here’s this guy in his 60s, still learning. If I were to go into a career like that, you are not just repeating yourself; you’re always be learning.

Then I heard Dick Williams speak, the great Canadian animator who had a studio in London, who had done a version of A Christmas Carol, the Dickens story, for American television, a half-hour special done in the style of Dickens’ illustrations, and that was beautifully done. I went to a retrospective of his work, and he spoke at it in Chicago in the 70s, again a totally passionate ambassador for hand-drawn animation. People in the audience were raising their hands, asking, “Can I come work for you?” and he was like, “No, I’ve got enough people at the moment.” But that made an impact on me.

At the same time, Christopher Finch, a British author, wrote a book on the art of Walt Disney, a big coffee-table book. For one of the first times, it identified who did what—naming artists like Ward Kimball, Frank Thomas, who animated Bambi on the ice, Milt Kahl, who did Shere Khan, and Ken O’Connor (I had O’Connor as a teacher later at CalArts), the great layout artist who designed the flight over London in Peter Pan. Anyway, it seemed kind of cool to me that you could make these big films and still be an individual, known for doing a certain thing. It wasn’t just Walt Disney doing everything—there’s artists doing these things.

That book also mentioned that Disney was starting a training program for young artists. What had happened was The Jungle Book came out in 1967, and Walt Disney had died in 1966. The Jungle Book was a big hit around the world, but they weren’t sure what they were going to do with the animation department because all the animators were in their 60s. Most of them were near retirement age or dying, and they hadn’t brought in younger animators. The studio realized that if they were going to keep things up, they had to bring in new talent. So, they started a talent program and talent search. I heard about that. They asked for a portfolio of animal drawings and all that. But, as I mentioned before, I have these allergies, so we had no animals at home.

I went to the zoo in Chicago, it was winter time when I was trying to put my portfolio together, and I was freezing, trying to draw the poor monkeys that were out there with me in the cold (much like Finland). I couldn’t stand it, so I realized, “Wait a minute, I can go to the Natural History Museum in Chicago” that has all these dioramas of animals, and 70 degrees Fahrenheit inside. So, I did my drawings there, and I thought they turned out okay. I sent them off to Disney, and a few weeks later, I got a rejection letter saying, “We didn’t like your portfolio. You don’t draw well enough.” In particular, they said my animal drawings were too stiff—well, of course they were! The animals I was drawing were stuffed; they were literally dead. I drew them exactly as they were!

Anyway, I also sent a portfolio to Marvel Comics and got rejected by them. But then, a few weeks later, Disney sent me another letter suggesting I send my portfolio to CalArts. They were starting a character animation program that was going to teach Disney-style animation, led by Disney veterans. Even though I already had this English degree, I thought, “Well, maybe I’ll try this at CalArts.” I sent them a portfolio, got accepted, and wound up going there for two years.

While I was at CalArts, the Disney review board came to look at the student work. They saw my work but didn’t realize I was the same guy they had rejected before. So they liked my work now, and they asked me to come work for them. So, I started at Disney in 1977—before you were born. It was the week that Star Wars came out in the U.S. I wound up working there for about 41 years.

Throughout that time, I had my ups and downs. There were times when our films were hard to make, or we had creative battles. Some didn’t do that well at the box office, and we were in the doghouse at the studio, hearing, “You guys don’t know what you’re doing.” We had to fight to make the next movie.

But overall, it was a fun ride, great support, I worked with great artists. I got to travel the world promoting these movies—we went to Scandinavia to promote The Princess and the Frog, we had journalist come from Finland and other countries in Stockholm. It was a fun ride, and I’ve enjoyed traveling to some of these places. I still want to get to Prague at some point, and I’d like to visit Finland too. I know Donald Duck is really popular there!

And I have three children. I have twin sons and a daughter. Both of my sons are in creative lines of work (not drawing, my daughter doesn’t draw either). One of my sons works for an ad agency that does movie posters and trailers—he’s kind of an art director there. My other son is a radio producer, podcast producer, and now he’s written some young adult novels, which is cool. My daughter is a family therapist. She has a very good design sense, but she does therapy.

I met my wife at Disney—she was a librarian in the in-house library. I met her right around when I started, and we’re about to celebrate our 45th wedding anniversary in a couple of weeks. She retired from the library once we had kids. She majored in English and Drama, and she’s very funny. She’s been a great supporter, an inspiration, and my muse in all these things. Overall, it’s been a wonderful thing overall.

Diana

And can you tell something about my favorite movie, “The Little Mermaid”?

John

When Eisner and Katzenberg came to Disney in the mid-’80s from Paramount, they brought a system with them to develop new movies. They didn’t know much about animation but they had a thing at Paramount called The Gong Show, which is based on the American game show. Basically, people would come to a table with Michael and Jeffrey to pitch ideas for possible films. If they liked them, they might put them into development after a brief pitch. If they didn’t like them, they’d go “Gong!” and you got yanked off the stage.

So, when The Gong Show was coming up in 1985, we were supposed to bring three ideas to the meeting. Ron Clements went to a bookstore and found a collection of fairy tales, where found The Little Mermaid, which he had never read before. He stood in the bookstore, read the story, and loved it. However, when he got to the end, he thought, “Ooh, this may take some work to craft at least a semi-happy ending.” He pitched The Little Mermaid at The Gong Show to Michael and Jeffrey. He even wrote a two-page treatment. At that point, I wasn’t involved, as I was pitching other ideas.

Initially, they said, “Gong, no, we don’t want to do it!” They were working on a sequel to Splash—the original Brian Grazer and Ron Howard movie, which was based loosely on The Little Mermaid. So they said no, we are doing the sequel, forget it, but then they went back and read Ron’s two-page treatment. Michael Eisner realized, “Wait a minute, Disney, fairy tales—this sounds like it could work.” So, they decided to put it into development. After a few months, they hired Michael Christopher, a live-action writer who wrote The Witches of Eastwick, to write a script on it. He had a very dark vision, and he quickly realized he wasn’t the right guy for this.

Ron and I had written together on The Great Mouse Detective, so Ron came to me and asked if I’d like to write the script with him. I said, “Yes, I’d love to write the script!” We pitched the idea of writing the script ourselves, and they agreed. We spent about 8 to 12 weeks working on it, and then we turned it in, they really liked it. They paired us with the great Howard Ashman, who had wrote The Little Shop of Horrors. He was not only a lyricist but really helped conceive how music would work within the story.

We met with him in New York City, showed him our outline, and he had ideas for how he thought the songs might help advance the story. He was off busy directing a play in New York at the time, so we wrote the script, and later, he started writing the music with Alan Menken. Howard eventually came to California, where he lived about three weeks out of every month. He had an office next to ours, and the music was written much like how it was for Snow White—in the same building right down the hall. Our musicians playing on the piano, “come down the hall, hear this song Under the Sea, here it is dadada” and we’d say “yes that’s great”. And Howard would be sitting on the piano, saying, “Play that figure again,” or “No, no, not that one, the other one,” he’d be there hammering away at the piano. And that’s how the songs were written.

We were storyboarding a few doors down, and the movie itself was made under trying circumstances because they kicked us off the Disney lot in Burbank, there was a big nice building Walt Disney had built in 1940. That building was home to all the ’40s films, as well as Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty. But when Eisner and Katzenberg came in, they wanted that building for live-action productions, so we were kicked off the lot and they put us into a warehouse in Glendale. It wasn’t a very picturesque setting—certainly nowhere near any water—and that’s where The Little Mermaid was essentially made.

We had a “sink or swim” mentality, so to speak. All of the artists were eager to do a fairy tale, since there hadn’t been a fairy tale in 30 years. There was inspiration to do something that wasn’t exactly like the classics but could still sit on the shelf with those. We wanted to reflect our own sensibilities, humor, and style of entertainment. So, we did, and it took us three years to make the film.

Throughout the process, they were yelling at us for spending too much money, even though the movie was produced relatively cheaply. We had no idea if other people would like it. We knew we liked it, and we loved the music. We held a public preview a few months before it came out, and it went amazingly well, the numbers were huge.

Jeffrey Katzenberg got dollar signs in his eyes – he realized, “Wait a minute, I can market this to a much bigger audience. It’s not just for kids—adults and teenagers can enjoy this too.” They developed multiple ad campaigns targeting different age groups. We had previously tried to sell them earlier on a poster featuring a mermaid on a rock, à la the famous statue in Copenhagen. Initially, they rejected the idea, they wanted something happy-go-lucky with all the characters. But after the successful preview, Jeffrey realized that adults might like it. One day during our sound mix, one of Howard’s assistants came down the aisle and showed us the new poster—a silhouetted mermaid on a rock, just what we tried to sell Jeffrey months earlier!

The dual ad campaign targeted both adults and kids, and that’s the way it played, it played to both audiences. The film was incredibly well-received around the world, and we were very relieved when it came out, because it was such a difficult movie to make, but we were always inspired by Hans Christian Andersen himself, music of Howard Ashman, and then all these young artists got a chance to showcase their talents. They had been somewhat suppressed on their earlier movies, but we encouraged them to go for it. It was really fun to give them a chance to display their skills, see what they can do, with talented individuals like Glen Keane and Mark Henn leading the way. Yes, it was fun.

Diana

How were the characters designed? Whose idea was for Ariel to have red hair?

John

Well, Ron, you wouldn’t know to look at him now, because he’s very gray, but he had very bright red hair back in the day. And I think it was his call to make her a redhead, because he had red hair, it fit her personality and it made her different than any of the other Disney heroines. We didn’t want to do another blonde or brunette, she was kind of fiery and she had this conflict with her father, and we even felt that her father had probably red hair too actually, then it went gray over the years.

But we wanted red hair, we had to fight our boss Jeffrey Katzenberg on that, he didn’t realize that we were going to do a red haired mermaid, and then he saw some shots in color where she had red hair and, he was like, “What is this? She’s supposed to be blonde! Don’t you know all mermaids are blonde!” I think he learned that from Splash. But he said “Jeffrey, not all mermaids have to be blonde.” He eventually gave in, albeit grudgingly.

The funny thing was, because he still was concerned about it when they made the dolls after the movie came out – he still was worried about her having red hair. So he first gave the dolls a kind of blondish reddish hair, because the word on the street was red haired dolls don’t sell. So all these girls said, “This doesn’t look like the movie!” So they had to redo the dolls with red hair, and after that, they couldn’t keep them in stores—they were flying off the shelves.

In fact, even the earliest walk-around character at Disneyland, because Jeffrey was approving it, had that same blondish-reddish hair. We had to point out, “Jeffrey, that’s not her!” They fixed that later too. We were happy to have a red-haired mermaid, and we think it really made her distinctive. Of course her hair color would pop against the blue of the water, creating that beautiful warm-cool contrast. So, yes, we were happy we had a red-haired mermaid.

We also had quite a journey with Ursula, the sea witch. At one point, there were lots of ideas floating around. She was almost a lionfish or a scorpionfish, to shoot spines from her body, but that concept was too complicated to draw. Then, one of our artists, Matt O’Callaghan, came up with the idea of making her half-octopus, and we liked that idea. He did some drawings like that, and Rob Minkoff, who did the original animation and later directed The Lion King, did this cool drawing of her that Howard Ashman really liked. Howard said, “Oh, her top half, she’s campy and vampy—she looks like a Miami Beach matron,” and he liked that.

So, we combined that Miami Beach matron vibe with this octopus, and a little bit of Divine, the cross-dressing guy from Baltimore who made movies with John Waters, films like Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble.

We had an earlier version that was sort of based more on Divine, and we showed it to Jeffrey Katzenberg. He was horrified because she had a mohawk and was very extreme, with tattoos and everything. He said, ‘Guys, this is too much. Way too much.’ So we had to pull back, which wasn’t a bad idea. We wound up with a sort of combination that we were very happy with.

The woman who did the voice for Ursula in America, Pat Carroll, passed away last year or so in her 90s. She was a lot of fun to work with and did an amazing job on the song. When Howard Ashman, who would write these songs, he would do the demos of the songs himself because he was an actor as well as a writer. He did the witch’s song with all the silkiness, and comedy in his demo, so when the actors were doing it, they were inspired by Howard’s demo and they had to live up to Howard’s version. He did ‘Under the Sea’ too, a funny version of that too, that Sam Wright, the American voice of Sebastian, was inspired by what Howard did on that.

Music was really a central part of “The Little Mermaid”. We tried to make the songs advance the story, so that you couldn’t cut a song out and still tell the same story. We feel like music works best when it’s so integrated into the story that it can’t be lifted out. Cause then it is just you stop the story to do a musical number and then you resume the story, which we wanted to avoid. But we wanted the story to have advanced from the beginning of the song to the end, which we feel like we did. I think that’s part of reason why it resonated, along with the infectiousness of Alan’s melodies and the cleverness of Howard’s lyrics. We didn’t know when we made the movie if anyone else would like it besides us. We had some movies before where, a month after it came out, we’d tell someone, “Oh, I worked on this movie or that,” and they’d ask, “When’s that coming out?” And we’d have to say, “It already came out.”

With The Little Mermaid, though, we didn’t have that problem. Everybody seemed to know about it, and it really reached a wide audience. Then it was reissued, and then they decided to put it on video a few years later, that widened the audience even more. We even got to go to Cannes—we went to the Cannes Film Festival, where it was shown out of competition there. They had a giant, inflated mermaid in the harbor by the Croisette.

So the Warner Brothers publicity person, this woman, was also doing Disney’s publicity at the time for Europe, as we drove in, she said, “All of Cannes is waiting for The Little Mermaid.” And we were “really?” We rounded the corner, and there was this giant mermaid in the harbor, with her arm extended. The weird thing was, of course, by the end of the festival, she had sprung a leak. So the statue’s arm was practically in the water. It wasn’t so good, but it was a lot of fun going to the festival and showing it there. They had walk-around characters, and we went down the Croisette. It was a far cry, as I say, from some of the earlier movies, where we’d do them, and no one would hear about them. But when we did like The Little Mermaid and later with Aladdin, the publicity department was so great at getting the word out around the world that it really became kind of a phenomenon everywhere. So that was great.

Diana

I also want to hear about Aladdin, another one of my childhood favorites.

John

Howard Ashman had originally developed a version of Aladdin that he was possibly going to direct as an animated film. He wrote a treatment and some songs for it, and they were trying to develop a script from that. This was while we were working on The Little Mermaid; he was off doing that after he had finished his work on Mermaid. However, the studio wasn’t liking the scripts they were getting based on Howard’s treatment, so they abandoned it and started developing other treatments.

When we finished The Little Mermaid, we were presented with three things they suggested we work on as for our next film. One was this thing with lions in Africa called The King of the Jungle. We thought, “Who’s going to go and see a movie like that?” So, we passed on that one. It ended up turning out pretty well, though. Then they suggested we do a version of the Swan Lake. There was a version they were kicking around at that, but we felt it was too much like The Little Mermaid.

The third project they had in development was Aladdin, which Howard had suggested. We really liked the idea; we were excited about the whole Arabian Nights thing, with genies, lamps, flying carpets and all that. So, we said yes to that. We resurrected Howard’s old version and added some new characters. There were too many human characters in the script that they had been developing at the studio outside of Howard’s treatment. In that version, Jasmine had a handmaiden. We decided to cut the handmaiden and give her a tiger as a pet, which would show how powerful Jasmine is by controlling such a big tiger like a little cat. For Aladdin, we gave him a monkey, thinking it would be fun for a street performer or con man to have a little monkey on his shoulder.

In Howard’s treatment, he had a parrot for Jafar, which we liked. Although they had moved away from that idea, we found it amusing. Howard had the idea of the parrot as being very talkative in private but acted like a typical parrot out in public, so we went with that idea.

We wrote the script for Aladdin, telling them, “Yes, we’d like to do Aladdin.” Ron and I developed our own version of the script, and we envisioned Robin Williams as our Genie. We didn’t know if he would do it, but we wrote the script as if he was going to do it, including all his quick changes and all that.

Eric Goldberg, the great animator who animated the Genie, took a comedy album that Robin Williams had done and did some animation to go along with the comedy album. He showed that to Jeffrey Katzenberg to sell him on the idea of Robin doing the voice. Jeffrey had seemed to be picturing that the Genie should just be this imposing, powerful guy, and he couldn’t quite imagine Robin Williams in that role. However, after seeing the animation, Jeffrey was sold on the idea. He brought Robin in, who was working on Hook at the time, or Toys or possibly another project—I can’t recall which one. He came in with his wife, looked at the storyboards, and really loved it, he said, “Yes, I’d like to do the movie.” So we proceeded to record with Robin in between his live-action filmings. In fact, even while he was rehearsing the song he was going to perform, while during the day for Hook, suspended in a harness against a green screen and he was exhausted. And it would be 10 o’clock at night, and we would come to his house that he was staying at in Beverly Hills, and the music director would be plunking it out on the piano and Robin would spend an hour rehearsing the song at, you know, 10 at night after a full day of shooting. It was very exhausting, but he was absolutely great to work with.

Of course, he improvised a great deal. He performed it as written also by Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio, who joined us as writers. But then we encouraged him to improvise, and certainly, he went to town, and we, Eric Goldberg, Ron and myself, would take everything he recorded, transcribed, and would construct a new scene out of his ad libs, and invent new lines that would make the ad libs work and all that, and create a new scene and kind of stitch it back together again. The scene that originally was this long became this long, using the best bits of Robin’s improvisation that each of us liked. That’s how it got reconstructed.

It was a blast to animate too, because we could do things that live action couldn’t achieve. While Robin couldn’t change the way he looked in live action, we could do it in a blink of an eye in animation. In some ways, it became the most “Robin Williams” movie of any of his catalogue of great films, we were able to take full advantage of his comedic volatility. It was a challenge, we were influenced by the artist Al Hirschfeld, the great caricaturist whom Eric Goldberg was a big fan of. We styled the movie somewhat like Al Hirschfeld’s work, because he has these very calligraphic lines. We also looked at Persian miniatures and calligraphy, aiming to infuse the backgrounds and characters with the elegant, serpentine quality of Persian calligraphy.

Eric really helped bring all the characters into the world of Hirschfeld with his cursive, rounded line effect—not angular at all. It was a challenge and it was fun. We knew we were taking a risk because we broke the fourth wall; we had the Genie talking to the audience sometimes and doing topical references. It was a risky move for a Disney feature to go as far outside the box as we did, but we believed that as long as the film had real emotion—whether in the friendship between the Genie and Aladdin, real emotion of the love story, or the threat from the villain, despite his campiness—it could still work and stand the test of time. I’m happy that people are still watching the movie, and it has inspired other generations. It led to a Broadway play and several live-action films, because the characters resonated. The movie, in many ways, is about wish fulfillment. Wouldn’t I like to fly on a carpet around the world, wouldn’t I like to find a cave full of treasure, if I were a guy to woo a beautiful princess, or if I were a girl to ride a carpet with a handsome dude? It taps into those basic things. And yet, the heart of the story is the friendship between Aladdin and the Genie. Aladdin promises to free the Genie, gets lost along the way, and ultimately fulfills his promise, learning that you don’t need to be dressed in a fancy outfit to be a good person. The clothes don’t make the man. So, it was a fun movie to do.

Diana

What were some challenges when making the film?

John

Well, the biggest challenge was, well, there were a couple. One was that, as we were just getting going, the Gulf War erupted in the Middle East. Originally, the movie was set in Baghdad, and Roy Disney, our boss, said, “You cannot do a movie set in Baghdad, given the world events going on right now.” So I took the letters from Baghdad and made an anagram, turning it into Agrabah, which is something I made up. It’s sort of an anagram, but it’s not Baghdad anymore.

To Jeffrey Katzenberg’s credit, even though there was trouble in the Middle East, he said, “We’re still forging ahead. We’re going to make this movie,” and it was okay. He could have bailed on the whole movie, so credit to Jeffrey for doing that.

But the other big challenge was, we worked on the script, storyboarded it, and put the whole movie up on what we call story reels (where we take all our storyboard drawings and add a very rough soundtrack), we had a 90-minute version of the movie that had no animation in it. We showed it to Jeffrey Katzenberg, and we were about a year and a half out from the movie coming out. When we showed it to him, he hated what we showed him. He had big expectations for what he was going to see because he liked some other movies in that vein, and he just didn’t get it. So he was like, “Start over.” We were like, “Start over? What are you talking about?”

At that point, we brought in new writers—Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio, who later went on to write Pirates of the Caribbean. They are wonderful writers. They came up with some new ideas, we came up with new ideas and we restructured the movie. In the earlier version, Aladdin had a mother, and part of his goal was to make things right for her because he was always goofing things up. There was a beautiful song called Proud of Your Boy, that Aladdin sang to his mother: “Proud of your boy, make you proud of your boy.” But Jeffrey didn’t like the mother character. He said, “The mum’s a zero! Get rid of the mom.” So, we got rid of the mother. Of course, my own mother later asked, “Why do you not have mothers in these movies? What did I do to you?” I had to explain, “It wasn’t us, Mom. It’s just the fairy tales don’t always have mothers.” So, with Ted and Terry, we rewrote the movie. The mom went away, that song had to go away too. Aladdin became an orphan, and we had to make all sorts of adjustments.

Fortunately, we got it together, and it worked. In the final movie you see, about a third of that is still what we originally had. A third is a rework of the original, and the last third is completely new. But we managed to get it done for the 1992 release. It was neck-and-neck though, and we were really working like crazy to get it done. It took three years to make the movie—Mermaid also took three years—but at a year and a half out, they told us to start over. That was a crazy schedule.

So, I’d say one of the biggest challenges was getting a story that Jeffrey liked and that we thought worked, and getting it done on time.

Diana

And what were some stories that you would have wanted to make as feature films when working in Disney?

John

Well, there was one that we wanted to do later on that we couldn’t, we had trouble getting the rights to it. It’s an interesting story based on a book by Terry Pratchett. I don’t know if you know Terry Pratchett, but he wrote the Discworld series. He’s a British author who died a few years ago. He wrote this book called Mort, which is set in his medieval fantasy world he created. It’s a comedy about a hapless kid who wants to apprentice to somebody in this world, and no one will have him because he’s kind of, you know, a bumbler. He winds up getting the only job he can: apprenticing to the Grim Reaper, who rides his horse and carries a scythe and all that. It’s actually a very life-affirming and funny story, but we had rights problems, we couldn’t get the rights because Terry Pratchett had sold some of them to a third party, and they couldn’t make a deal. So, that was one we didn’t get to do.

We pitched other ones along the way. We had a Norse mythology movie that we didn’t get to do, which might have been fun. That was before they had made any of the Thor movies, and now, of course, Norse mythology has many movies in its area. But we were pitching one a long time ago, and it didn’t quite go through. We had pitched them doing a version—and finally, they’re doing it—of Roald Dahl’s book The Twits, which is a very funny book about this couple that does crimes, enlists animals to do crimes for them, and they’re a horrible married couple who are very mean to each other. They’re finally making it. I think Netflix is doing it finally, and I think Taika Waititi might be involved. I’m not sure if it’s live-action or animation; I think it’s animation, but that’s a cool story.

There have been these projects along the way that we hoped to realize, but they didn’t happen. You know, there are still other fairy tales out there that seem like they could be interesting, but I won’t mention them. Generally, we got to pursue many of our own ideas, like The Little Mermaid, Moana, and Treasure Planet. Those three movies were generated by us. The others (which we really liked)—Aladdin, Hercules, and Princess and the Frog (which was originally called The Frog Princess)—were ones already in development.

I think fairy tales are fascinating because of their primal nature. You can invent a whole world, and there’s always a clear arc to them. I’m not crazy about sequels to fairy tales because a fairy tale has its own arc. It doesn’t lend itself to a sequel the way something like The Incredibles does, where they can go on another adventure. That seems fine, but I’ve never been fond of taking a fairy tale doing another one after it.

Diana

And how do you delegate responsibilities with a co-director?

John

Because we co-wrote together, we had already hashed out a lot of our creative issues. When we wrote the script, we were like left and right hands on a piano. Ron is great with structure and editing, and he’s funny too, but I’m more into improvisation and create comic business. Basically, we would construct the outline of the story together, and then I’d go off and write ahead of Ron, I would improvise on paper. I’d write each scene 10 different ways, then give it to Ron. He’d read it, circle the parts he liked, and incorporate those. Sometimes he wouldn’t like any of it and would write a completely new scene. He told me “I don’t want you to read what I’m writing, because it’s going to slow me down until we have the whole script done”. So, I’d feed him stuff, but I wouldn’t read what he assembled until about eight or ten weeks later, when he would hand me the first rough draft of the script. By then, I’d written so many versions that I couldn’t even remember half of them. I’d read the script and ask, “Why didn’t you use my part for this scene?” He’d say, “That is your part.” I’d look back and realize, “Oh yeah, I wrote that.”

So, we hashed out a lot of things before the directing part. When it came to directing, we worked very collaboratively on most directorial assignments, but we also divided the movie into sequences. He directed some sequences, and I directed others. We had grown up in a system with multiple directors, you know, at Disney. When Disney was making Snow White and Pinocchio, they had multiple directors, although they had a strong producer, Walt Disney, who really put his stamp on those films. As directors, we wanted to have a similar role in controlling the creative thing, but there was enough work that having two directors was helpful. So, we divided the movie into sequences: he directed some sequences, and I directed other sequences. But we always showed each other what we were working on. We got together in the editing bay as the footage came in, to review the footage together, give notes on what worked and what didn’t work, and to pick the takes we were going to use together. We were always present for all the recording sessions, and we reviewed character designs and color footage together. It was very much a collaborative enterprise.

By dividing up the work into sequences, we also created our own little “kingdoms,” so to speak. We each worked with our own team of animators on different sequences. This allowed us to put our own stamp on the work while still keeping it unified. It was great because we were very simpatico. We were the same age, both from the Midwest of the U.S., and both born Catholic—he went another direction, into La La Land somewhere, but I remained a Catholic. We liked the same movies and Disney films, we had the same sense of humor, we were both comic guys, and both valued heart and emotion in our stories as well, it was paramount that you get that into it. We made a good team because we saw things enough alike, yet we were different enough to complement each other. He brought things to the party that I couldn’t, and I brought things he couldn’t. It was a happy marriage, although by the end of our careers, we did resemble a bickering married couple. We had our tiffs—nothing heated, just the little habits that develop over 40 years of working together. We’d accuse each other of interrupting and so on. But overall, he was a great, collaborative partner and a brilliant guy. I’m very lucky and happy to have worked with him, and the movies wouldn’t be the same without him—or without me. We’re both happy with how they emerged.

Diana

You both met at Disney, right?

John

Yes, he came there in that training program. Even though we were the same age, he got to Disney a few years before me because he didn’t go to college. He went straight from high school into the industry, where he worked for a TV station back in Iowa. And then, he moved to Hanna-Barbera for a while because he couldn’t get into Disney right away. Once he got in, by the time I joined Disney, he was already established as an animator. He had worked on Pete’s Dragon, The Rescuers, and The Fox and the Hound, and he was a really good animator.

Ironically, the more he animated, the less he liked animation. He really liked storytelling and writing than animating, so he eventually left animation. I, on the other hand, was doing animation but later moved into story as well. I got to know him first on The Fox and the Hound when he was animating and I was animating, and that’s how we got to know each other. He was a very funny guy and very smart.

We really worked for the first time on The Great Mouse Detective. Ron had pitched the idea to the studio, based on the book Basil of Baker Street by Eve Titus. I thought it would make a fun feature, and they put it into development. They liked the idea, so originally, I was assigned to direct the movie. Then Ron came on board after me. Ron and I ended up teaming up on it; we both directed and wrote for the project. That’s where we first worked together.

Before that, we also worked together on The Black Cauldron for six months to a year, though we faced some challenges there. The directors didn’t like our ideas, so Ron and I bonded over the fact we couldn’t get any of our ideas through to the other directors. I was a director on that film, but I never got to direct anything because they shot down all my ideas. I had wanted to use some Tim Burton designs for the movie, and they didn’t like that, they didn’t like the story ideas, they were like “let’s use more of the book and less of the other stuff”. So Ron and I, in a way, were banished from the The Black Cauldron, and we moved on to Basil of Baker Street. Those two films were the ones where we really bonded and collaborated initially.

Diana

What was it like working on ”The Princess and the Frog”?

John

That was a fun! You know, the studio had moved away from traditional hand-drawn animation, but it really owes its return to Disney’s acquisition of Pixar and John Lasseter being put in charge. John, my old college classmate, loved hand-drawn animation and really wanted to continue hand-drawn. He gave us the option on The Princess and the Frog, which was amazing.

Disney had been developing a version of the book The Frog Princess, where the princess, not the prince, gets turned into a frog. In the meantime, Pixar was also working on a concept for The Frog Prince set in New Orleans, an idea developed by their art director, Ralph Eggleston. When John Lasseter came in from Pixar, he said to us that, because we had been banished from Disney actually for about six months because we couldn’t get a project off the ground, he wanted to bring us back. He suggested we look at the Frog Prince idea, thinking we could come up with a good angle on it. We looked at both versions and we said we liked the New Orleans setting, but thought the heroine could be African American and she could be the one turned into a frog. We could use elements of voodoo as the magic. John loved our pitch and sent us to New Orleans, since neither Ron nor I had been to New Orleans. We got to go to the bayou, met with a voodoo priestess, we went and heard jazz in the French Quarter, and experienced all the great things New Orleans has to offer. It was great. So, we incorporated those elements into the script when we wrote it and brought on Rob Edwards, an African American writer, to help with the first pass. We really felt like we were tone-deaf to certain things, so Rob came in, helped us out, and was our co-writer on the script. We also got to work with animators like Eric Goldberg, who had done the Genie, and Mark Henn, who had done Jasmine; he did Tiana on this. For the villain, we brought in Bruce Smith, a fantastic animator who had worked on Tarzan, though we hadn’t worked with him before. He’s an unbelievable draftsman and animator. We also hired Betsy, a choreographer I used to work with at the studio, to shoot reference footage incorporating 1920s eccentric dance things for Dr. Facilier.

It was certainly a challenge to make the movie as we were trying to make a movie that would be more aware, trying to make a movie that would be sensitive to certain racial issues. It was tricky to navigate certain things, but we really liked the idea of having this African American heroine who was not a traditional princess. She worked as a waitress and dreamed of owning her own restaurant—this kind of real-world dream was novel for Disney and had never been done before. We were inspired by Leah Chase, this great African American restaurateur in New Orleans’ French Quarter who owned Dooky Chase’s Restaurant. She made it a landmark that hosted presidents, kings, and regular people, and served great Creole cooking. So, Leah Chase’s influence was a part of our inspiration for the film.

Diana

I think it’s a very beautiful film, and I myself would like to see more movies like that.

John

We really loved it, John Lasseter loved it, and the preview audiences loved it too. It was really well previewed. But still, there’s this ongoing issue where CG films were doing better than the hand-drawn ones. And so, at a certain point, the studio committed completely to making CG films, which we were disappointed about. I hope someday they reconsider. They’ve done some little short projects, and even on Moana, the tattoos on Maui were hand-drawn by Eric Goldberg and then mapped on. I still think that a well-done hand-animated feature could do well at the box office if the story is strong and characters are good. So I am hoping that this art form stays alive, even if it may not initially come from Disney. It’s almost in jeopardy now, as many of the animators who started out are now in their 60s. Eric Goldberg is in his 60s, and while there are great young animators coming up, they need a venue and projects to demonstrate what they can do. I hope hand-drawn animation continues, but I also love CG. I don’t think it’s one or the other; they do different things, and stop-motion as well. Look at what Guillermo del Toro, Tim Burton, and Henry Selick have done with stop-motion in films like Coraline are fabulous. I like seeing the art form go in different directions. And the Spider-Verse movies, I think, have been great in terms of stretching the boundaries and blurring them. They explore what animation can be by using all these graphic elements to tell a story that takes advantage of the fact that it isn’t live action. I think those films have been pretty fantastic. So, that’s exciting.

Diana

What advice would you give to young filmmakers starting in the industry?

Well, I still believe that drawing is an important skill to have, even if you’re working in CG or stop motion. It helps artists communicate their ideas effectively. So, I would encourage all artists to develop their drawing skills as a way of communicating their ideas. It’s a great foundation, no matter what medium you work in.

I’d also say, take full advantage of the resources available to you during your time in school. There are so many books, podcasts, and online programs on animation now that we didn’t have back when I started. You can make your own films and study animation in ways that weren’t possible before. When I started, there wasn’t even VHS. I had to use Super 8 films—tiny, 10-minute cut-downs of “Snow White” and “Pinocchio”—and I’d study the animation with a little viewer. But now, with DVDs, with online, with these programs, you can make your own film. You can study animation in ways you never could before. You have these books, you have these podcasts, you have just a million ways you can learn about animation and try and develop your own skills, even if you don’t go to an expensive animation school, you can do it with these other things. There are so many ways to learn on your own if you have the discipline.

I think there’s a way you can kind of learn them yourself, but you’ve got to do it. You can’t just think about it; you really improve by working hard and by showing your work to others and receiving criticism. What you need to learn is to accept vulnerability and put yourself out there, being willing to hear criticism, which isn’t always fun. You have to get over being defensive. You might be defensive initially, but try to reflect on whether the critics have a point.

Writing is like that. Animation can be like that. Storyboarding certainly can be that way. You need to be willing to jump back in the same material, identify its flaws, and improve it. I encourage young people to do those things—show your work, work hard. Carry a sketchbook. If you’re nervous about drawing in public, you’ll have to get over it. I had that fear too. When I first started drawing in public, I was worried people were watching me. But no one really cares what you’re doing. You’re in your own little world, and capturing life on the fly is a great way to your powers of observation. Animation, after all, is rooted in your ability to observe the world and the people around you. What makes this person’s walk different from others? How do they express joy in a way that’s unlike anyone else? A child has ten different ways to show happiness—what are some of those variations? Start to absorb those things, and then your synthesis of all these influences will take shape.

You’ll use elements you’ve seen in films or from other people, but when everything mixes together in the gumbo of who you are, it will come out uniquely yours. It may have elements of other things, but you’ll be presenting your vision of the world, having developed your voice and your point of view. Obviously, if you’re working in a big studio system, you’re showing your work to people, and you have to sell them on your voice. But it’s important to understand what you respond to emotionally and creatively—what you want to share, comment on, or offer insight into. And animation is a great medium for that. It combines so many different disciplines—it can involve drawing, sculpture, painting, dance, filmmaking, cutting, staging, dramaturgy, and even physics and science, incorporating real-world effects and principles like inertia and things like that.

Eric Larson, years ago, my mentor, once said that our only limit in animation is our ability to imagine and to draw what we can imagine. I would update that now—given the new tools, our only limit is our ability to imagine and to communicate those ideas by whatever means are available. And now, there are many ways beyond drawing to do that. So, that is a very broad canvas, and that in itself is inspiring, offering the freedom to communicate ideas that can make the world a better place in some way.