Stuart Ginsberg makes his directorial debut with IT’S A to Z: The Art of Arleen Schloss, a documentary exploring the life of underground art pioneer Arleen Schloss. Ginsberg, who met Schloss while working at the School of Visual Arts in the late ’90s, spent over a decade crafting this film, which delves into her influential role in New York’s alternative art scene of the 1970s-1990s. Through rare footage and interviews, Ginsberg highlights Schloss’s groundbreaking work in performance, video, and experimental art, and her role in shaping the careers of artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Sonic Youth.

What initially drew you to Arleen Schloss’s story, and what aspects of her life and work did you find most compelling?

I met Arleen when I worked as the Director of Communications for the School of Visual Arts (SVA), an art college in New York City. We had mutual friends through the School, and in 2003, Arleen was a thesis advisor in the MFA Computer Art Department at SVA. At an end-of-the-year thesis exhibition at the school, I began to talk to her.

During our conversation, Arleen mentioned her loft in the Lower East Side of New York City, a place where, in the 1980s, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Eric Bogosian, and the originators of Sonic Youth used to hang out. Having grown up in the suburbs of New Jersey, just 20 miles away from Downtown New York, I was always intrigued by the New York art scene from the 1970s and 1980s and the people who influenced its art, performance, and music scenes.

I’m particularly drawn to lesser-known, yet influential figures, and I learned that Arleen not only presented and curated the work of major artists but also created her own art. She excelled in various art forms, including spoken word, performance art, painting, installation art, and experimental art. When I researched her online, I noticed that whenever she was in a group show, her work was often singled out and praised as one of the best in the exhibition. I found myself wondering , “Why isn’t she better known?”

Overall, I find Arleen’s sound, performance, and video works the most compelling. For example, she once filmed a street scene and later incorporated it into a different type of video work for a spoken word poem called, “How She Sees It By Her.” Arleen made it seem as though she had shot that scene specifically for that piece, but she hadn’t. I’m Intrigued by how she combines seemingly incongruous elements to create something entirely new.

Given the vast amount of archival footage you had to work with, how did you approach the process of selecting which pieces to include in the documentary?

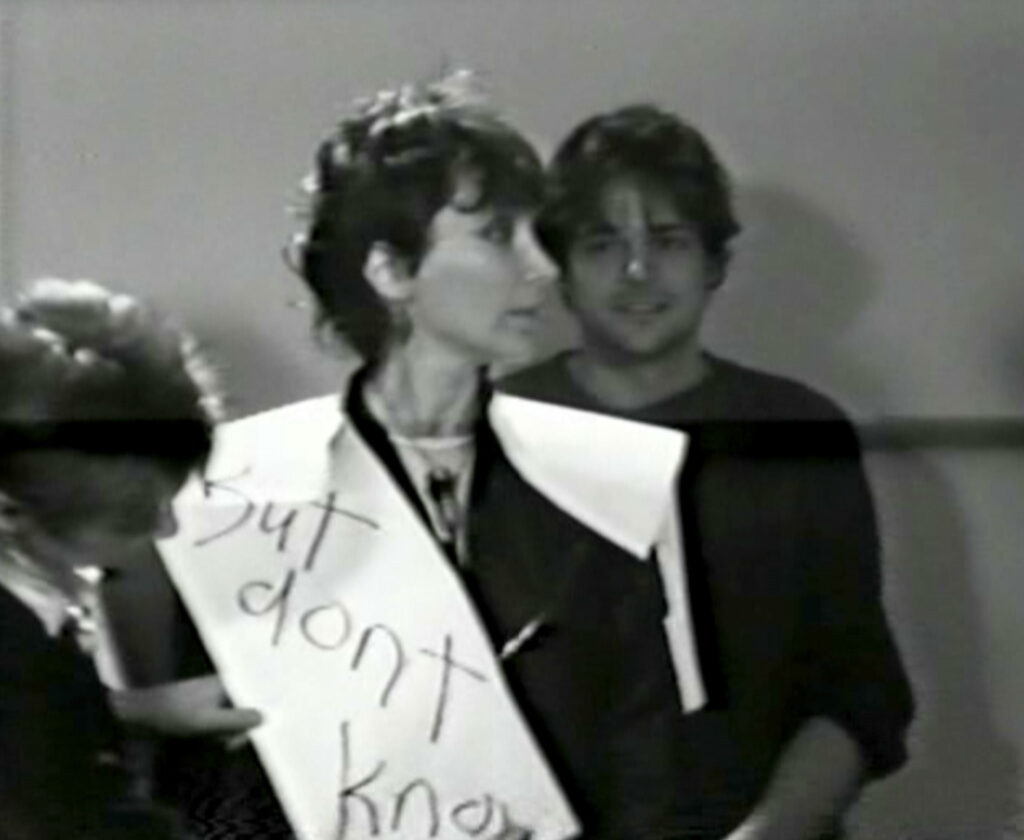

When reviewing her archival footage, Arleen and I sat next to one another in her loft. We reviewed over 600 hours of VHS footage – a lot of it fast-forwarded. With each tape we viewed, I took extensive notes. As I sat with Arleen, I realized I had to learn about the Downtown underground art scene first. I admit, I wasn’t familiar with experimental composer and theorist John Cage, but I realized how important he was to her, and I didn’t know about the prestigious show Ars Electronica, produced in Linz, Austria. I realized I had to include both John Cage and Ars Electronica in the film. When starting the documentary, I learned she performed at Ars Electronica from people I worked with at SVA. Two, in fact, made it known to me how important Ars Electronica is and that should be included.

As an experimental artist, Arleen experimented with different video and film formats so it was important to show the work that she exhibited with new video and film formats. Additionally, I selected footage that reflected what people said and what helped move the story forward. I knew Arleen’s place A’s is important to the New York loft art scene and interviewees also mentioned the importance of her performance at the Museum of Modern Art in 1978.

And finally, and probably most importantly, Arleen herself helped guide me. She would point to the screen and say, “that’s major. … MAJOR! You need to include that.”

Arleen Schloss was known for embracing emerging technologies and new art forms. How did you ensure that this pioneering spirit was effectively conveyed in your film?

I took the approach of “show, instead of tell.”

Wherever I could, I decided to show Arleen’s work. For example, the film shows footage of Arleen performing at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1978, a period when most museums were not showing performance art. There are shots of Arleen presenting her work live on TV video monitors, something that we take for granted today, but at that time, most people hadn’t seen that in an art performance project.

Some of my interviewees did mention Arleen using new types of cameras for shooting video and for mixing various art forms with lasers – lasers were used in 1986 at the Ars Electronica show in Linz. With Ars Electronica,I wanted to show as much of the performance as I could and howArleen mixed new technology with dance, movement, singing, and music.

Can you share some challenges you faced during the decade-long process of making this documentary, and how you overcame them?

With independent filmmaking it’s always about time and money. Funding resources and trying to cut the footage down, and finding the right people for the project. With this type of project, I realized it’s important to work with t people who are passionate about the project, and who have what I call “skin in the game.” Meaning, they have the same need and desire as you have to share the story and get it out into the world.

Cutting the footage down was the first challenge. I had an assemble edit of 3.5 hours, and it took a while, but I finally found an editor who understood Arleen’s world and knew some of the people in it.

In terms of overcoming the challenges, I was fortunate to find the right people to help me. I went through three editors. They all were great, but I realized I needed someone who was passionate about the time period, and the editor I used did know Arleen. Additionally, I found talented producers, as well as music and sound people who knew Arleen or lived in her old neighborhood. The key is to find passionate people who share your vision.

However, the larger challenge was Arleen’s health. Arleen has MS and when visiting, I began to help her with household tasks, like getting her laundry or going food shopping for her. I made a deal with Arleen. When I visited to help her with those tasks, I would spend a few hours reviewing footage and the documentary story, and then help her.

In 2014, she suffered a terrible fall down the steps of her loft and has a traumatic brain injury from the fall, I had to stop working on the film for a few years and spent time helping her move from A’s to another apartment in New York.

How did your background in public relations, independent film production, and teaching influence your approach to directing your debut feature-length documentary?

It always starts with knowing what makes a good story and how to tell a story. Being in public relations and teaching allowed me to understand how to make a story sound compelling. I started with the most intriguing information first, and then parceled out information in a way that ultimately makes viewers want to learn more.

I am a lifelong learner. With this project, I asked myself, “Why are they doing this? What ideas or art movements have influenced them? The idea of creating unexpected events or happenings influenced by the Fluxus movement were appealing to me. I wanted to delve deeper into the loft art scene in New York City and the idea of “everything is art” and figured other people would be interested as well.

What was the most surprising discovery you made about Arleen Schloss or the downtown New York art scene during your research and filming?

The most surprising aspect is the extent to which no one cared about critics or selling their art work. Arleen’s group of friends were there just to have fun and create. This became a growing theme in my research and changed how I viewed the overall Downtown New York art scene.

There were two different scenes. One one was the more commercial scene that consisted of SoHo and the galleries, but the underground art scene of which Arleen was a part, people first cared about being together and working together. Of course, when gallerists started to recognize the underground artists (the non-SoHo artists), things changed.

With Arleen herself, I was surprised by how prolific and talented she was. She created so much art in so many different art forms, and excelled at those forms and had been one of the first artists to experiment in those art forms. For example, she included live video feeds and slides in her performance art, which in the mid 1970s, is something that was considered new and experimental. Arleen was an early adopter of many different art forms.

How do you see the influence of Arleen Schloss’s work and ethos reflected in today’s art and technology landscapes?

The idea of being interested in the process of art-making as well as the end product of the art itself is something that we see in today’s art world. The idea of having the audience as part of the art-making process and remixing and editing various art forms to create their own art is something that’s commonplace today. You can go to an art exhibit and interact with a piece through virtual reality glasses a QR code, or through touchscreens.

For example, when a new movie trailer comes out, people will create their own trailer of that movie. We see that whenever a new superhero movie is released. TikTok is another example. People will remix songs or take a snippet of a quote and lip sync to that quote or song, creating their own performance piece.

The idea of the audience becoming part of the art making is not a new concept, but technology has made it easier for the audience to reinterpret art, video, and music. Website are a mix of the written word, video, color, and animation. The comments section and memes created and shared by people are another example of making art and ideas more accessible. They’re shared.r. It seems as if having interactivity and audience involvement is a big component of commercial and noncommercial art.

Art on the blockchain further democratizes art-making and lowers the barrier to entry for artists. Arleen and her friends believe in encouraging greater participation in the art-making process.

In what ways do you hope this documentary will contribute to the legacy and recognition of Arleen Schloss in the broader art world?

I’d like to have audiences understand that an art career is not just a person who only shows and sells art pieces at an art gallery. Arleen’s video art, performance art, as well as her curating and organizing events throughout New York City and the world had a great impact not just on the Downtown New York art world, but the experimental art world, in general. Whenever she was in a group exhibition or video program, her work was typically flagged as being the best in that particular show.

In her loft A’s, Arleen often gave working artists their first performance or art exhibit – both well-known and not so well-known. Artists, filmmakers, and musicians such as Aei Wei Wei, Martin Wong, Shirin Neshat, Alan Vega and Martin Rev of Suicide, Eric Bogosian, Steve Buscemi, Thurston Moore & Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth, Carolee Schnemann, and Jean-Michel Basquiat, all performed at Arleen’s loft or in other shows she curated in New York at the beginning of their careers.

What message or feeling do you hope audiences take away after watching “IT’S A to Z: The ART OF ARLEEN SCHLOSS”?

I hope people take in a message of do your best to enjoy what you do. If you’re not able to devote eight hours a day to what you want to do, try to carve out time to do it anyway. Whatever you’re interested in, find like-minded people who can support and nurture your interests, talents, and creativity.

Official website of the film – https://www.artofarleenschloss.com/