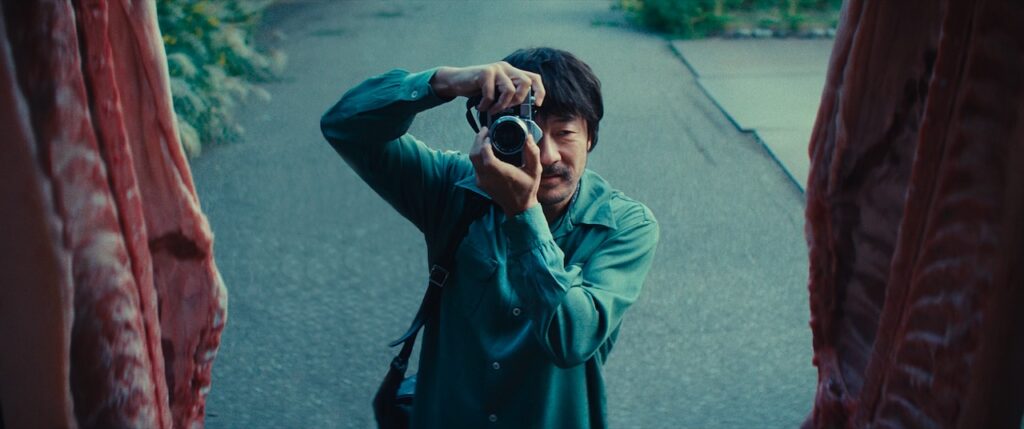

Ravens is an uncompromising and remarkable cinematic achievement by director Mark Gill, vividly transporting audiences to the 1960s and 1970s with an authentic portrayal that captures the haunting beauty of Japanese photographer Masahisa Fukase’s life through a bold, imaginative lens. Anchored by Tadanobu Asano’s (47 Ronin, Shogun) brilliant performance and a striking portrayal by Kumi Takiuchi as the artist’s muse, Yoko Wanibe, Ravens masterfully explores the highs and lows of creative obsession, making it essential viewing for anyone drawn to films about artists. Recently captivating audiences at the Tokyo Film Festival and winning the Audience Award at the Austin Film Festival, this standout feature is set to continue its festival circuit with upcoming screenings in Taipei and at the Red Sea Film Festival. Ravens is undoubtedly one of the finest films of 2024, delivering a powerful and unforgettable cinematic experience.

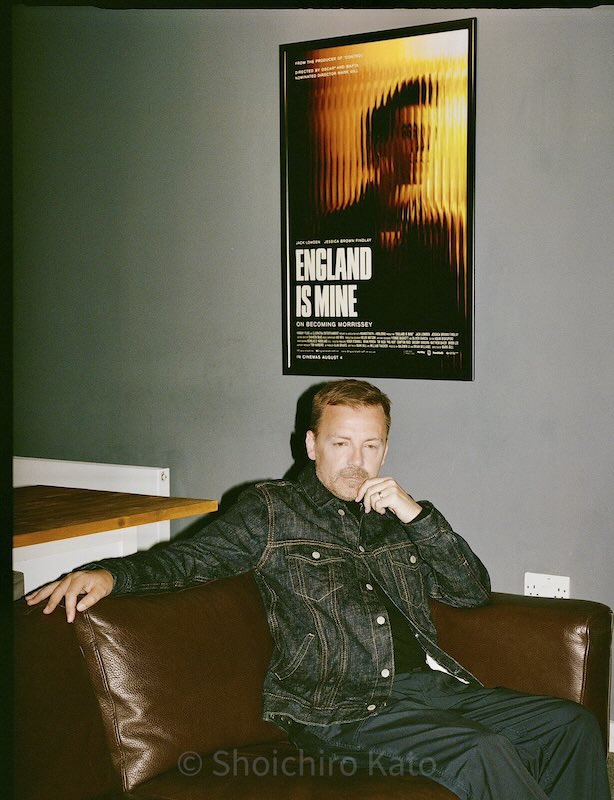

In this exclusive interview, Gill sheds light on the process of bringing Fukase’s complex life to the screen. Known for his brooding, provocative imagery, Fukase’s work was steeped in dark introspection—a challenge for any filmmaker, especially one with roots outside Japan. Yet Gill, the English director celebrated for the Morrissey biopic England Is Mine, dives deeply into Fukase’s mind, crafting a realm where art, love, and inner demons converge in a stunning blend of drama and fantasy. The film’s inventive use of a human-sized, talking raven—a manifestation of Fukase’s inner turmoil—infuses the story with a unique psychological intensity that’s both unsettling and captivating, bringing an almost mythic element to the narrative.

Gill reveals how he was drawn to Japan’s cultural richness and the profound love story between Fukase and his wife and collaborator, Yoko Wanibe. This fascination led him to make unconventional choices, including the addition of the raven as a vivid metaphor for Fukase’s inner struggles, along with infusions of Japanese folklore that give the film its unique edge. Here, Gill discusses his inspirations, the challenges of filming in Japan, and his pursuit of authenticity while offering a fresh perspective on a gifted yet troubled artist.

Indie Cinema Magazine: Did you initially want to shoot a film in Japan, or did that desire come specifically after discovering Fukase’s story? What drew you to Masahisa Fukase’s life and work as a subject? How did his story resonate with you personally?

Mark Gill: I discovered Fukase’s story during pre-production on England is Mine so can’t remember if I was specifically thinking about what my next project might be or not. I’ve always been strongly drawn to Japanese culture and I do recall I was looking at adapting a Yasunari Kawabata novella so maybe something was in the air. It was primarily the power of the love story between Fukase and Yoko that put the hook in me. His work is obviously powerful and more importantly varied. I think this was an important factor, as his work seems to reflect his life at every step. I guess if anything during this period I was drawn to the idea of the creative struggle which is part of both my films and something I can resonate with totally.

IC: In “Ravens”, Yoko is portrayed not as a muse but as an essential collaborator. How did you approach shaping her role in the film, and why was it important to make her a central character?

Mark: Yoko is central to Fukase’s story. For me the best work is directly or indirectly influenced by her presence or lack of. I met the real Yoko in 2019 and this really helped in getting to know her as a character. Yoko is forthright, opinionated, strong willed, witty and kind. From my limited understanding I got the sense that Yoko represented a lot of the frustrations Japanese women felt during this period, that of being reduced to a bit part in the lives of men. Plus Yoko had to navigate both the influence and allure of Western culture with that of the expectation of being a traditional Japanese wife.

Once I’d spent time with Yoko and gathered opinions of her from those who knew her during her marriage to Fukase there was no way she was just going to be reduced to a mere muse. Yoko had her own dreams and ambitions.

IC: The Raven, as a human-sized creature embodying Fukase’s inner thoughts, is a bold narrative choice. What inspired this decision, and how did you envision the Raven adding depth to Fukase’s character?

Mark: One of the things I learned during researching Fukase is that he was quite taciturn. Not great for a movie. So I needed something to get him talking. Having read enough Japanese literature and Manga I knew of the TENGU (a kind of supernatural mischievous being). Once I’d set my mind on this it was just a case of finding the right one from Japanese stories. I settled on TSUKUYOMI (who i affectionately call Yomi-chan) the moon god who it is said manifests as a raven. I wanted Yomi-chan to represent that inner voice we all have. Especially in the creative world where there is a constant internal discussion about whether we are doing the right thing, are we sacrificing enough for our chosen art or sacrificing too much? I wanted to get this internal dialogue out onto the screen in the most entertaining way possible.

IC: Filming in Tokyo during the summer must have presented unique challenges. Could you share some memorable experiences from the set?

Mark: The heat. The heat. The heat. Being from Northern England where anything above 25 degrees is a national emergency having to deal with both heat and humidity was something I’d not experienced before. I’d say this was the most challenging thing especially in locations where there was no air conditioning.

But I have to say that despite this, everyday on set was magical – I loved every second of working with my cast and crew. I’d say the most fun we had was on the ferry, being buffeted by the sea it also gave us a break from the Japanese summer oven.

IC: How did your background in both music and graphic design influence the film’s tone, visual style, and the way you approached scenes that blur reality with dark fantasy?

Mark: I think as a musician I understand rhythm and dynamics pretty well. And I worked hard to bring this to bear in the film. I designed the movie carefully to follow patterns which are expressed in a number of different ways. Music is always important in creating the right tone and a lot of the music in the film was actually chosen at the writing stage. I like to create a playlist when I’m writing to put myself in the right mood. I think it’s worked out great.

IC: Fukase’s work, especially “Ravens”, has a haunting quality. How did you work with your cinematographer, Fernando Ruiz, to capture the emotional intensity and contrasting moods within the story?

Mark: As an outsider I see Tokyo in wide screen. So shooting the film using spherical lenses was never an option for me. I asked Fernando to source a set of vintage lenses that would bring a lot of character to the image. However vintage lenses can be unreliable and can slow a production down if you get a bad set. Luckily Fernando discovered the Hawk Vintage 74 range. A modern lens with a vintage look. This was quite a bold choice and Fernando was initially unsure if it was too much. But once I saw what they could do I fell in love with them. They are so unique, especially at the edges of the lens they go a bit wild. So I thought they were perfect. The only other consideration was that I wanted always to be close to the emotional intensity of the actor’s faces and using anamorphic allowed me to do this while retaining the width I like.

IC: As a British director delving into Japan’s post-war Shōwa art scene, what considerations did you have to respect the cultural context while bringing an outsider’s perspective?

Mark: I just had to listen to my Japanese team. I having an especially close working relationship with producer Megumi Ishii, who acted as both my script translator and cultural advisor. The last thing I wanted was my Japanese audience to be pulled out of the movie due a bad choice made by a ‘foreign director’. It’s something I’ve seen way too much.

IC: How did you ensure authenticity when portraying Japan’s 1960s and ’70s art world, and what research went into recreating the era?

Mark: Again I just had to listen to the guidance. Listening is an underrated part of the director’s toolbox.

IC: Did you collaborate with any Japanese artists, historians, or cultural consultants during the film’s development?

Mark: No – I just did my own research or worked with my Japanese team. They know their country better than anyone. All I needed to do was check whether an idea was plausible and if not, then tweak it to fit the Japanese mindset.

IC: How do you hope “Ravens” will influence the way audiences see Fukase and his legacy as an artist?

Mark: I’ll be happy if the film raises awareness of this unique and brilliant artist. I always think audiences should be left to make up their own minds. Ravens is just my artistic point of view and not a definitive statement about him. I think he’s too complex a character for that.

IC: What have been some of the most meaningful reactions to “Ravens” from those familiar with Fukase’s work, and from those discovering it for the first time?

Mark: The most meaningful feedback I’ve had is from the Japanese audiences. To be told I’ve made a true Japanese movie and not an outsider’s fantasy idea of what Japan is, has been something I’ll treasure. But to also see the film be so positively received and engaged with by a Western audience in Austin told me that Ravens also has a universality that transcends borders.

IC: The film shows Fukase’s struggles with his “inner demons” in a literal and metaphorical way. How do you think this aspect resonates with today’s viewers, especially creatives who face similar internal conflicts?

Mark: I think everyone has inner demons and it doesn’t matter if you’re creative or not. I suspect we all have an ongoing internal battle with ourselves.

IC: Reflecting on the journey of creating “Ravens”, what has been your biggest takeaway as a filmmaker?

Mark: To always back and trust myself.

IC: Is there a particular genre, historical figure, or theme you hope to explore in future projects?

Mark: After two back to back true life stories I think I’m done with biopics for a while.

IC: How do you balance your interests in film, music, and photography, and do you see yourself bringing these fields together in your next work?

Mark: All three disciplines have defined my life. So there’ll always be a huge part of anything i do creatively.

I just follow my heart and listen to my instincts, oh and my inner raven.

Mark Gill

Mark Gill is a British filmmaker, writer, director, photographer, and musician from Manchester, whose artistic journey began at 18 with a recording contract at Warner Music, leading him to join Monaco, a band formed by New Order’s Peter Hook; after fifteen years in music, he shifted focus to film and photography, quickly gaining acclaim as a director with a unique aesthetic and psychological depth. His short film The Voorman Problem (2011), starring Martin Freeman and Tom Hollander, earned Oscar and BAFTA nominations, marking him as a standout in cinema; his debut feature England Is Mine (2017), distributed by Hanway Films, explores Morrissey’s early life and stars Jack Lowden and Jodie Comer, closing the Edinburgh International Film Festival and receiving a Michael Powell Award nomination. His film career initially began with The Bloomsbury Cellarmen, a music documentary winning the Royal Television Society Student Award for Best Documentary Film. Ravens is his second feature film.

Official website of Mark Gill: https://www.markgill.co.uk/