On May 31, 2025, Clint Eastwood turns 95—an age few actors, let alone filmmakers, reach with their legacy not only intact but still evolving. For Eastwood, it’s another quiet milestone in a career defined by independence and a lifelong refusal to conform. Over more than seven decades, he has transformed from a television actor into a global movie star, from a genre icon into an Oscar-winning director, and ultimately into one of American cinema’s most enigmatic and enduring figures—a true artist of reinvention.

Born in San Francisco in 1930 during the throes of the Great Depression, Clinton Eastwood Jr. grew up in a world shaped by scarcity. His early years were peripatetic, moving frequently as his father sought work during the economic downturn. Drafted into the U.S. Army during the Korean War, Eastwood was stationed at Fort Ord in California, where he met aspiring actors and got his first taste of performance. After the war, with no formal acting training, he ventured into Hollywood.

His breakthrough came in the late 1950s with the television western Rawhide, where he played Rowdy Yates, a young, impulsive cowboy learning the ropes on the cattle trail. Though the role made him a familiar face to American audiences, it largely kept him within the bounds of conventional Western storytelling. It wasn’t until the early 1960s that Eastwood’s screen presence took on a new dimension, thanks to Italian director Sergio Leone. Leone saw something more than youthful charm—he saw mythic stoicism, a man who could project strength, mystery, and danger with barely a word. Casting Eastwood in A Fistful of Dollars (1964), a bold reimagining of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961), Leone helped create a new kind of antihero: morally ambiguous, emotionally withdrawn, and endlessly compelling.

The Dollars trilogy—A Fistful of Dollars (1964), For a Few Dollars More (1965), and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)—redefined the Western genre and catapulted Clint Eastwood to international stardom. The trilogy culminated in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, a sprawling, operatic masterpiece widely regarded not only as one of the greatest Westerns ever made but as one of the most influential films in cinema history. Despite initial skepticism toward the so-called Spaghetti Westerns—European productions with unconventional style and sensibility—the films grew in stature over time, their bold visuals, morally ambiguous characters, and Ennio Morricone’s unforgettable scores earning them critical and cultural reverence.

Eastwood’s directorial debut, Play Misty for Me (1971), was a psychological thriller in which he also starred. The film follows a radio DJ who becomes the target of a dangerously obsessive fan. Set in the coastal town of Carmel-by-the-Sea, California—where Eastwood would later serve as mayor—the film showed his early interest in moody atmosphere, character-driven tension, and tight pacing. It was well-received and marked Eastwood as a promising director with a natural sense for suspense.

Eastwood returned to familiar Western territory with High Plains Drifter (1973), a surreal film that blurred the line between reality and nightmare. As both director and lead actor, Eastwood shaped a ghostly, allegorical tale that diverged from traditional Western heroism. With its stark imagery, eerie score and ambiguous protagonist, the film showed Eastwood’s willingness to push genre boundaries and explore darker, more symbolic narratives. In the film, Eastwood plays a mysterious stranger who arrives in the small, corrupt mining town of Lago, only to take on the role of both protector and avenger after the townspeople reveal their dark secrets.

Released the same year as High Plains Drifter, Breezy was a significant departure from Eastwood’s image. He directed but did not appear in this romantic drama, which tells the story of a middle-aged man’s relationship with a free-spirited young woman. Quiet and introspective, Breezy revealed Eastwood’s interest in intimate human relationships and emotional realism, highlighting his range as a filmmaker willing to tackle sensitive subject matter with subtlety and restraint.

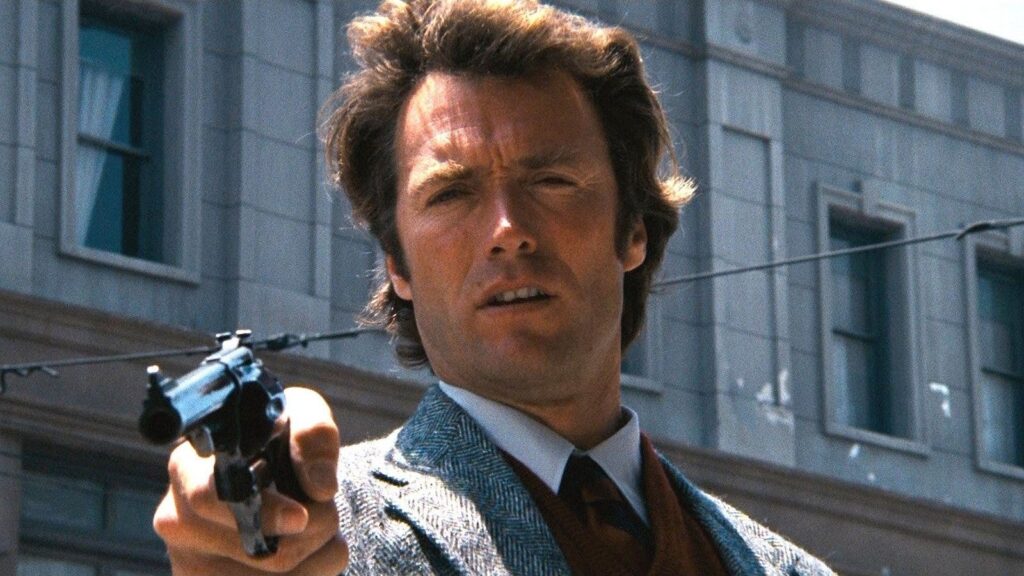

In the 1970s, Eastwood continued to reinvent his screen persona with Dirty Harry (1971) directed by Don Siegel, a film that introduced Inspector Harry Callahan, a cop fed up with bureaucracy and moral relativism. Callahan was brutal, sarcastic, and unafraid to act outside the law—a character who sparked debate and controversy, becoming a symbol of right-wing authoritarianism for some, and a cathartic antihero for others. Yet Eastwood always played him with a hint of irony, allowing audiences to question their own reactions. The film cemented his box-office reputation and launched a franchise, but more importantly, it gave Eastwood control; he began directing more of his own films, developing a stripped-down, efficient style inspired by mentors like Don Siegel.

Eastwood’s direction was never showy, but it was precise. He rarely exceeded a few takes, trusted his actors, and avoided technical flourishes. Over time, this efficiency became part of his myth—an old-school filmmaker who worked fast and under budget, often making personal films within the Hollywood system.

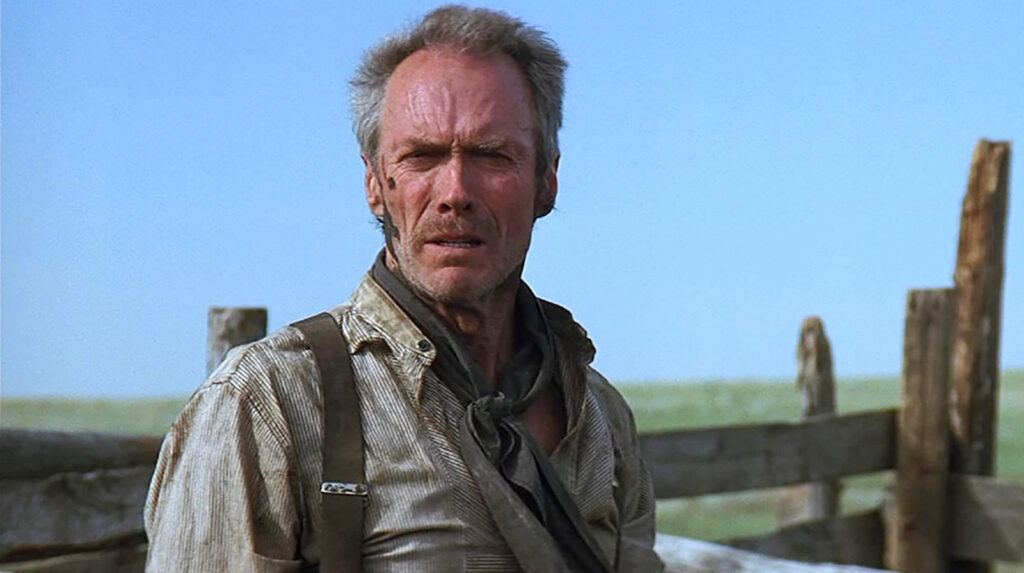

One of the best films of Clint Eastwood as director and actor is The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), a gritty, elegiac Western that not only showcases his iconic screen presence but also reveals his growing mastery behind the camera, as he crafts a deeply human story of loss, vengeance, and reluctant redemption, following a Missouri farmer-turned-guerrilla fighter who, after the Civil War, becomes a fugitive hunted by his own countrymen, all while forming an unlikely surrogate family and confronting the moral cost of violence in a land still scarred by conflict.

In the 1980s, Eastwood’s highlights as director were the haunting, atmospheric Western Pale Rider (1985), in which he evokes the mythic lone rider archetype while subtly echoing his earlier roles to tell a story of spiritual reckoning and frontier justice in a corrupt mining town, and the intimate, melancholic biopic Bird (1988), a passion project about troubled jazz genius Charlie Parker, through which Eastwood, a lifelong jazz aficionado, demonstrated a surprising sensitivity and stylistic boldness, blending fragmented narrative, moody visuals, and richly textured sound to create one of the most artistically ambitious and emotionally resonant films of his career.

In the 1990s, Clint Eastwood directed a series of deeply resonant and thematically rich films—Unforgiven (1992), A Perfect World (1993), White Hunter Black Heart (1990), and The Bridges of Madison County (1995)—that together marked a high point in his career and confirmed his evolution into one of American cinema’s most thoughtful and versatile auteurs. Unforgiven, often regarded as his masterpiece, is a revisionist Western that deconstructs the myths of frontier heroism and violence, centering on William Munny, a retired killer drawn back into his brutal past for one final job; with its stark realism, moral ambiguity, and haunting tone, the film earned Eastwood Oscars for Best Director and Best Picture, and it signaled a major turning point in his cinematic legacy. Following that triumph, A Perfect World offered a quieter but equally affecting meditation on innocence, fatherhood, and redemption, as Eastwood, in a supporting role, directed Kevin Costner in one of his finest performances as an escaped convict who forms a tender bond with a young boy during a tense manhunt across Texas—revealing Eastwood’s growing interest in emotional nuance and moral complexity. In White Hunter Black Heart, Eastwood took a more self-reflexive turn, portraying a fictionalized version of director John Huston in a film that grapples with ego, obsession, and the blurred boundaries between art and personal recklessness, creating one of his most intellectually curious and self-critical works. The Bridges of Madison County showed Eastwood at his most emotionally restrained and mature, directing and starring opposite Meryl Streep in a profoundly moving story of fleeting love and personal sacrifice, where the quiet intensity of everyday life becomes the backdrop for a life-changing affair.

In his later career, Clint Eastwood reached new artistic heights with Mystic River (2003) and Million Dollar Baby (2004), two critically acclaimed dramas that showcased his mature, restrained directorial style and deepening interest in moral ambiguity and human tragedy. Mystic River (2003) explored childhood trauma and retribution in working-class Boston. Million Dollar Baby, ostensibly about boxing, is in fact a deeply tragic story of a fiercely driven female boxer who rises from hardship with the help of a grizzled trainer, unfolding into a powerful meditation on dignity, the weight of personal choice, and a quiet, unwavering love expressed through profound sacrifice. It earned him his second Best Director Oscar. Letters from Iwo Jima (2006), told from the perspective of Japanese soldiers during World War II, revealed Eastwood’s commitment to empathy and complexity—qualities not often associated with a man once known for delivering justice with a magnum revolver.

His films in the 2010s and beyond—Gran Torino (2008), American Sniper (2014), The Mule (2018), and Cry Macho (2021)—have continued to explore enduring themes of masculinity, regret, alienation, and the possibility of redemption, often through aging protagonists grappling with their pasts. His 2024 legal thriller Juror No. 2 has been widely praised as one of the most accomplished works of his later career, a taut, morally layered film that reflects his ongoing interest in personal responsibility and the gray areas of justice. While critics have occasionally debated the political undertones of his work, Eastwood has avoided making overtly ideological films; instead, he has consistently delivered deeply humanistic stories, his characters are often flawed, burdened by guilty conscience, yet rendered with a surprising compassion and emotional depth that challenges the simplistic image of Eastwood as merely a stoic tough guy.

Eastwood’s off-screen life mirrors his independence. He has never been one to play the Hollywood game. He avoids red carpets, rarely gives interviews, and has never chased celebrity. He served as the mayor of Carmel-by-the-Sea in the 1980s, built his own production company, Malpaso, and has composed scores for many of his own films, a rarity for film directors, which places him in the company of Charlie Chaplin and John Carpenter. His musical sensibility—rooted in jazz and classical—reflects the same restraint and melancholy found in his visual storytelling. At an age when most filmmakers have long retired, Eastwood continues to work—not for money or accolades, but because he still has something to say.

There is also something symbolic about his continued presence, as Hollywood becomes increasingly a conveyor belt of predictability, while Eastwood represents a vanishing idea of American filmmaking—one influenced by international art-house, personal in vision, and unafraid of ambiguity. His work ethic is monastic. By refusing to dwell on past triumphs or chase passing fads, he remains relevant, with films that continue to resonate across generations.

At 95, Eastwood stands as one of the last living links between Hollywood’s golden age and its digital present. He is older than Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and Steven Spielberg, yet younger directors—Denis Villeneuve, Christopher Nolan, Quentin Tarantino—cite him as an influence not only for his cinematic style but also for his fierce independence. In a town built on illusion, Clint Eastwood has always stood for something real; a kind of truthfulness that is impossible to fake.

To celebrate his 95th birthday is not merely to honor a career. It is to pay tribute to a way of being in the world: steady, enduring, curious, and unsentimental. Clint Eastwood has always walked slightly apart from the industry he helped define. He does not cling to the spotlight, yet it follows him. He does not mythologize himself, though his work is steeped in myth.

In the end, perhaps the truest thing about Eastwood is this: he never really played cowboys or cops or killers. He played men shaped by the myths of masculinity—only to slowly dismantle them. Over time, his films became elegies for a certain kind of manhood, not celebrations of it. In Unforgiven, the aging outlaw William Munny is no longer a legendary gunslinger, but a haunted man trying to outrun his past. In Gran Torino, the gruff veteran Walt Kowalski clings to outdated notions of pride and prejudice, only to find redemption in empathy and sacrifice. Even in his most iconic roles, Eastwood didn’t glorify violence or dominance—he questioned them. His greatest legacy may not be the myth he helped build, but the honesty with which he took it apart.

Happy 95th, Clint. The last cowboy still rides.