In the spring of 1960, French cinema was transformed when Jean-Luc Godard’s À bout de souffle (Breathless) premiered in Paris. Sixty-five years later, it remains not just a cornerstone of the French New Wave but an emblem of artistic rupture—a declaration that cinema could breathe differently, speak in fragments, and move with the improvisational spirit of jazz. More than a film, Breathless was an intervention: a playful, violent break from tradition that inaugurated a new freedom in both form and attitude. Set against postwar Europe’s cultural reawakening, the film captures the youthful rebellion and existential uncertainty that defined the 1960s. With its raw energy, jump cuts, and naturalistic performances, it shattered the polished conventions of classical filmmaking and rewrote the grammar of cinema.

Godard, then a 29-year-old critic at Cahiers du Cinéma, made his directorial debut with a story treatment by François Truffaut. Working with minimal resources, Godard shot the film quickly on the streets of Paris using natural light, handheld cameras, and few permits. Cameraman Raoul Coutard famously hid his gear in a baby carriage to avoid attention. Improvisation wasn’t just a stylistic choice—it was a necessity, and a virtue.

The plot is deceptively simple: Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo), a small-time car thief obsessed with Humphrey Bogart, kills a police officer and goes on the run, hoping to flee to Italy with his American girlfriend Patricia (Jean Seberg). The film was loosely inspired by a 1952 article about Michel Portail, a real-life car thief whose American partner added a layer of myth to the tale. Truffaut developed the treatment with Claude Chabrol, though both passed directing duties to Godard. With their endorsement and a chance meeting between Godard and producer Georges de Beauregard, Breathless found its unlikely path to production.

Though the final screenplay stayed close to Truffaut’s structure, Godard wrote much of the dialogue on set, famously describing it as “a boy who thinks of death and a girl who doesn’t.” Truffaut later noted that Godard’s decision to end the film with a violent death, rather than the original ambiguous finale, reflected his darker, more melancholic vision.

At the heart of Breathless lies a deep humanism. Godard’s camera doesn’t merely follow a plot—it observes people. Michel and Patricia aren’t heroes or archetypes; they are flawed, impulsive, contradictory—human. The famed hotel room sequence, where they talk, flirt, argue, and fall in and out of love, captures life as it is felt: messy, unpredictable, deeply personal.

This observational, experience-driven approach rejects artificiality in favor of lived emotion. In Breathless, the camera is less a manipulator than an accomplice—witnessing rather than directing.

The film’s radical use of the jump cut, pioneered by Godard and editor Cécile Decugis, fractured cinematic time and space in ways that startled audiences. Rather than hiding edits, Breathless flaunted them. The camera lingered, then jolted forward. Dialogue scenes stuttered and skipped, embracing disjointed realism. Critics initially called it sloppy or amateurish; Decugis recalled it being labeled “the worst film of the year” before release. But these stylistic ruptures were deliberate—a kind of cinematic punk rock, decades ahead of its time.

Jean-Paul Belmondo, in his first starring role, emerges fully formed as a magnetic screen presence—cool, unpredictable, and impossible to ignore. His performance as Michel defines the film’s spirit, blending swagger and vulnerability with casual brilliance. He didn’t just act the role—he embodied a new cinematic attitude.

Belmondo’s career mirrored his on-screen duality. Initially embraced by auteurs like Godard and Truffaut, he later reinvented himself as a box office star in popular action films—often performing his own stunts with fearless athleticism. Whether brooding or wisecracking, he remained a singular force in French cinema.

Jean Seberg, just 21 when Breathless was filmed, brought a striking naturalism and emotional ambiguity to Patricia. Her close-cropped hair, half-smile, and ambiguous gaze helped define the New Wave heroine—aloof yet vulnerable, modern yet timeless. An Iowa-born Hollywood ingénue, she found greater artistic freedom in France. But her offscreen life was marred by political persecution: targeted by the FBI’s COINTELPRO for her civil rights activism, she was hounded by false rumors. In 1979, at just 40, she was found dead in her car under mysterious circumstances. Her story was later dramatized in the 2019 biopic Seberg, with Kristen Stewart portraying her ordeal.

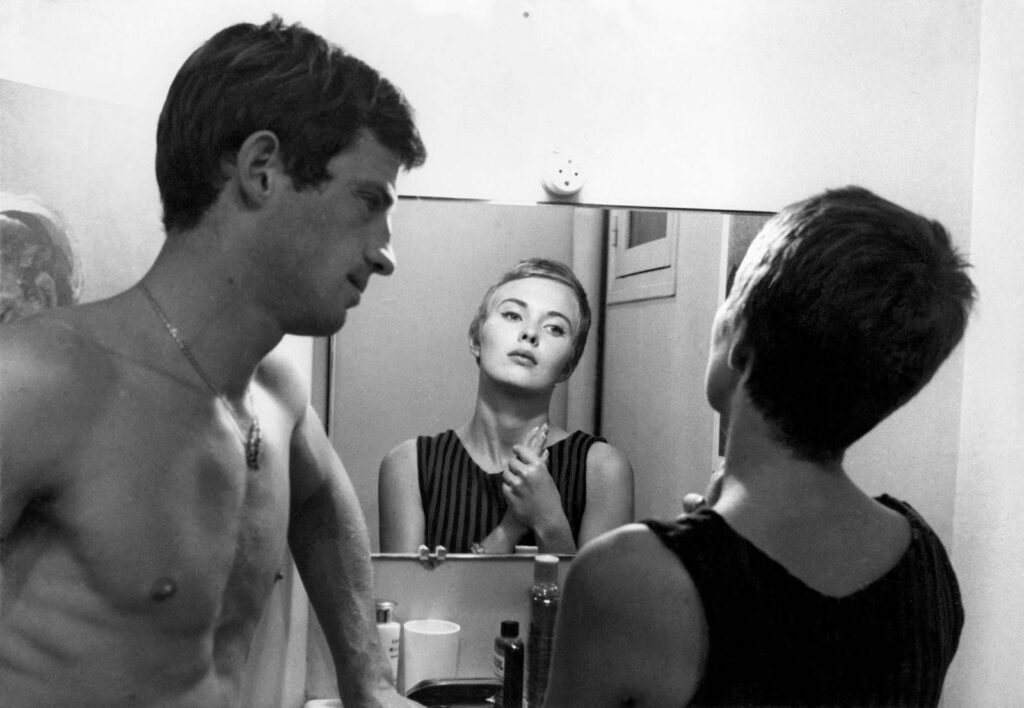

Michel and Patricia’s long apartment conversation—nearly twenty minutes of meandering dialogue—is among cinema’s most iconic scenes. Sex and death orbit each other in Godard’s ironic fashion, reflecting not just a relationship but a worldview. Their connection is fragile, filled with crossed signals and existential drift. The film offers no easy resolution—just two people trying, and often failing, to make sense of each other and themselves.

The arrival of Breathless coincided with a broader cultural upheaval. Postwar France, disillusioned with tradition and colonialism, was ready for reinvention. Youth culture surged. American pop culture collided with European intellectualism. Existentialism filled the air. The French New Wave was already stirring with The 400 Blows and Chabrol’s early films, but it was Godard who exploded the medium. While others nodded to Hollywood, he deconstructed it. Michel’s doomed heroism is constantly undercut by parody. His stylized death is both homage to noir and rejection of its illusions. Breathless is not just a film—it’s a film about film.

Its influence is immeasurable. It didn’t simply reflect a changing world; it helped create one. Shot with handheld cameras and natural light, it felt alive, immediate, full of possibility. This raw spontaneity—cinema’s version of fresh air—is embedded in every frame.

Over the decades, Breathless has remained uncannily modern. Its techniques influenced generations of filmmakers, from Scorsese to Tarantino. Its youthful rebellion still resonates in a digital age increasingly mediated by algorithms and effects. Godard’s belief—that a film could begin anywhere and end anywhere—became a cornerstone of independent cinema.

Certain images have entered cinematic folklore: Belmondo in a fedora, thumbing his lip like Bogart; Seberg selling the New York Herald Tribune on the Champs-Élysées; the lovers walking and talking, caught between freedom and fate. These moments endure not because they advance a plot, but because they capture a feeling—ephemeral, rebellious, beautiful.

The film’s performances feel improvised, unfiltered. Belmondo, with his loose charm, seems to simply be. Seberg’s unreadable expressions and dry detachment make Patricia more than a muse—she’s a mystery. The actors don’t perform; they exist. This naturalism was revolutionary. It made audiences feel less like viewers and more like voyeurs of real life.

Today, Breathless may no longer shock—but its sense of freedom remains radical. Its provocations now live in textbooks, yet the film still whispers its subversive message: cinema can disobey. Godard gave the world a permission slip—rules can be broken, and in that breakage, new truths can be born.

Jean Seberg died in 1979, Belmondo in 2021, and Godard in 2022. Yet Breathless endures—unfazed, unbowed, unmistakably alive.

There was a 1983 remake starring Richard Gere. In 2025, Richard Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague explored the making of Breathless, even attempting to echo its style. But the original remains singular. Everything that followed—homage, remake, imitation—feels like a shadow of something genuinely bold and world-changing.

Looking back from today’s landscape, Breathless feels like an antidote to digital slickness. In an era dominated by green screens and prepackaged plots, Godard’s raw, intuitive approach reminds us what cinema can be: a street, a camera, two people talking.

Breathless isn’t just a film; it’s a declaration. It insists that cinema can be free, personal, intimate—and still powerful. It reflects life as it’s lived: with jagged rhythms, unresolved tensions, and flashes of grace.

Sixty-five years later, its legacy persists—not just in technique but in ethos. In a world increasingly blurred between real and artificial, the film’s fresh air still feels revolutionary.

It’s worth remembering a time when a young filmmaker grabbed a camera, stole some sunlight, and dared to change everything. And À bout de souffle is still running—still gasping, still glowing, still out of breath.