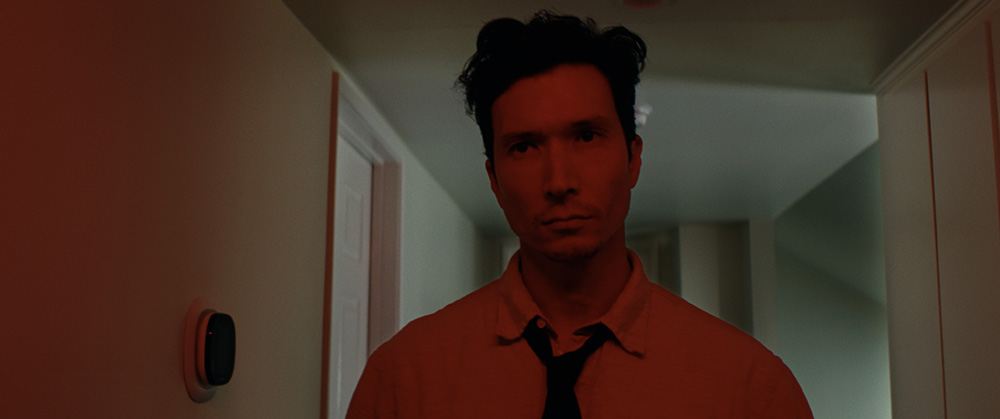

In the short film This Is Not My Beautiful House, director Mark Tompkins delivers a gripping psychological drama that explores trauma, revenge, and the power of false narratives. The film follows an ordinary man entering a suburban home filled with haunting memories, blurring the line between reality and delusion. Originally based on a satirical voice-over monologue, the short evolved into a tense study of a mind unraveling. In our interview, Tompkins shares insights into his creative process, lessons from his debut feature “Warmed-Over Krautrock”, and how he brought this unsettling vision to life.

Your short film “This Is Not My Beautiful House” deals with complex themes like trauma, revenge, and the grip of false narratives. What was the initial spark that led you to explore these ideas?

A couple years before the pandemic, I wrote the voice-over narration on a piece of notebook paper, almost on a whim, in a process that felt like automatic writing. Meaning I just kept going without editing or self-censoring. It was the monologue of a man whose insecurities had gotten the better of him, and the fact that he heard the monologue as a woman addressing him in the second person just showed how far gone he was. How he was losing touch with reality.

I put those notebook pages away and forgot about them. But post-pandemic there was a moment, circa 2021, where I wanted to be around other people again, but also had intense anxiety about it — I kept thinking I wanted to go into the office where I worked but hide under the desk once I got there. Somehow this short, based on the monologue I’d written earlier, became an indirect way of expressing that anxiety about being around other people.

The protagonist in your film enters a house that holds painful memories. What role does the setting of the suburban home play in the narrative, and how did you approach creating the atmosphere within this location?

This lavish suburban home is an ideal of success and domesticity that’s out of reach for the lead character. The voice-over indicates the house is the site of a marriage that went terribly wrong, so this tranquil-looking setting is now filled with poisonous emotions for the lead character.

I started drawing storyboards and realized that the compositions should be off-balanced, to create an uneasy feeling. I thought that if I combined those setups with jump cuts, we could create an alienated perspective on a mundane suburban home.

You mentioned the film explores how someone can be in the grip of a false narrative to the point of committing violence. How do you think this theme resonates with today’s societal issues?

I’ve never viewed the film as inherently political. But I think it’s indirectly relevant to the world we’re in today, where people seem to be increasingly susceptible to false narratives, and no kind of objective reality can penetrate the way they wall themselves in with false narratives.

The voice-over in the film originated from automatic writing and touches on a man’s deepest insecurities. How did this voice-over evolve from its initial satirical intent to become something more ominous?

It was like a shift from a first-person perspective to the third-person. At first, being inside the head of a man who hears a woman’s voice berating him, it felt like he could be this hapless, almost comic figure. But as I started to picture this man creeping through a suburban house with that running through his head, it became clear he’s a loose cannon, and maybe a threat to other people, or to himself.

You’ve described filmmaking as an exercise in problem-solving. Could you share a particular challenge you faced during the production of “This Is Not My Beautiful House” and how you overcame it?

We had to make a big, sunny suburban home in southern California — a location that looked like it should a high-end real estate listing — feel ominous. It took a lot of prep work, from storyboards to walking through every part of the house with our very talented DP, Nathaniel Regier. All the while we were asking ourselves, how do we put a distorted, psychological spin on this? The camerawork, color grading, sound design and score all combined to subvert what in real life looks like a very comfortable, inviting setting.

Given that “This Is Not My Beautiful House” was designed to pull the rug out from under the audience in a very short time, how did you approach pacing and editing to ensure the story delivered maximum impact in a brief runtime?

The story was structured so that as the lead character moves from room to room in the house, his thoughts grow darker and the mood gets more ominous. But I knew the tension would break if we stretched it out too long. I cut some of the voice-over even before we started filming, and then during post, the editor, David Carlos Valdez, and I agreed we should cut another few lines. That helped the filmmaking breathe, and kept the story taut, I hope.

Having learned from the process of making your debut feature film “Warmed-Over Krautrock”, what were some key lessons or techniques you applied to the production of this film?

More intensive pre-production. For instance, we picked the clothes that the actors would wear based on what would fit their characters, and even what day of the week we decided it would be (in the film), but I also brought in the DP and we talked about how the clothes would mesh with the lighting and the overall production design. This time I was much better about ensuring there were no unwelcome surprises on set.

You’ve mentioned wanting to maintain the initial spark of inspiration throughout the production process. How did you manage to keep the energy and creativity from auditions all the way through to post-production?

A big part of it was a much tighter timeline. I drew storyboards in February and March, we scouted locations and held auditions in April, shot the film over a long weekend in May, edited it in June, and had the score by August. (And it would be disingenuous not to mention, everyone who worked on the film got paid promptly, even if it was a modest rate. That helps people feel like they’re contributing to a production where their work is valued.)

But I also have to credit having a very capable producer, Meghan Weinstein, who handled many of the logistics in preproduction and for the shoot. Working with an efficient producer, the filmmaker gets to concentrate on the creative aspects of the film.

How did you transition from screenwriting into directing and producing your own films?

After writing scripts for years, I wasn’t satisfied with just sitting in front of my computer any more. I wanted to be working with other people. So I wrote a screenplay (“Warmed-Over Krautrock”) that I could shoot using my own humble savings as the (micro)budget.

But another key was that I knew a few recent film school graduates who wanted to do something more than work as production assistants on car commercials and music videos, so I hired them to work on the movie. They were glad to work on a feature, even if it was a tiny production.

With your film, “Warmed-Over Krautrock”, you experienced both the highs of the shoot and the lows of the prolonged post-production. How did those experiences shape your approach to filmmaking

Maybe the most valuable lesson is that an independent filmmaker, or any filmmaker just starting out, can always find people who want to volunteer for, or accept a very modest salary for, the glamorous, exciting side of filmmaking — I mean acting, being on set, everything to do with the actual shoot.

But when you get to post, that’s the less glamorous, far less public side of filmmaking. But you’re going to need a competent/professional sound mixer, and a competent color grader. You’re much less likely to find people who will volunteer for those roles, so make sure you still have the budget after your shoot has wrapped to hire a sound mixer, someone to do color correction, to do the titles, etc. You need those talented craftspeople long after everyone else has moved on to other projects.

What do you hope audiences will take away from “This Is Not My Beautiful House”, especially regarding the film’s exploration of false narratives and personal trauma?

Without giving too much away, I think in the end it’s an empathetic portrait.

On a less highbrow note, I hope the audience will enjoy that we build up a tense, creepy atmosphere and then the film turns into something else, without (I hope) feeling like a cheat. You could even view the movie as a peculiar kind of fun.

Looking back on your journey from writing screenplays to directing films, how do you feel your creative identity has evolved, and where do you see it heading in the future?

I like the idea of “escaping the script,” with no disrespect meant toward screenwriters. My feature was too tethered to the dialogue, and as I sat with the editor, I realized we didn’t have enough footage to do some montages that would have helped the movie take flight a bit more. “This Is Not My Beautiful House” is a step toward becoming more visually expressive, and experimenting with the form. I want to build on that.

After completing this film, what are your plans for future projects? Do you see yourself continuing to work within the psychological drama genre, or are there other genres you’d like to explore? Are you planning to make a new feature film soon?

I like the idea of a small-scale work that, if you pull it off, speaks to much larger concerns. The film I plan to make next is a comedy that would run 30–35 minutes, focusing on two characters, mostly in one location. I want the challenge of making that cinematic, and to work closely with the two actors.

After that — a filmmaker can always dream — I have a couple feature films I’m dying to make, one a heist comedy with two female leads, while the other is dark comedy/horror. My hope is that the humor in these stories can speak to the world of today without leaving the audience feeling bludgeoned.

Given the lessons learned and the success you’ve achieved with your first feature film and now this short, what advice would you give to aspiring filmmakers who are just starting out?

Don’t go into making a film with the mindset that you’re going to be a one-person band —approach collaboration with an open mind. Other people’s ideas (the DP, an actor, the sound mixer) can make your film a lot better. It’s all about finding the right people.

Above all, sit with the editor. Don’t treat the editor like a software program that’s just there to carry out your instructions. Watching an editor work, and collaborating with them, will give you lots of ideas of what you could do differently next time.

Official website of Mark Tompkin’s feature film “Warmed-Over Krautrock“: https://www.warmed-overkrautrock.net/